Simon Willis in 1843 Magazine:

When Vachirawit Chivaaree, a popular Thai actor, posted four pictures of cityscapes on Twitter last year with the caption “four countries”, he knew what he was doing. One of the four he listed was Hong Kong, which, as furious Chinese nationalists were quick to point out, is not a separate country, despite its special status within China. Pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong and Taiwan sprang to the defence of Chivaaree, who was subjected to a fusillade of abuse. Among their responses was a meme: cartoons of milky drinks from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand “holding hands” in solidarity against authoritarian government in all its forms.

When Vachirawit Chivaaree, a popular Thai actor, posted four pictures of cityscapes on Twitter last year with the caption “four countries”, he knew what he was doing. One of the four he listed was Hong Kong, which, as furious Chinese nationalists were quick to point out, is not a separate country, despite its special status within China. Pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong and Taiwan sprang to the defence of Chivaaree, who was subjected to a fusillade of abuse. Among their responses was a meme: cartoons of milky drinks from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand “holding hands” in solidarity against authoritarian government in all its forms.

The symbolism was clear. Whereas people in South-East Asia drink their tea and coffee with milk, the Chinese prefer their oolong and other brews unadulterated by dairy – or so their detractors claimed. The meme became a movement, the Milk Tea Alliance. Its members swap tips about dodging internet firewalls and avoiding arrest. The group includes Hong Kongers and Taiwanese worried about the looming shadow of the Chinese Communist Party (China considers Taiwan to be a renegade province that will one day be reclaimed). It also unites Thais critical of the country’s military government and protesters in Myanmar opposed to the junta’s coup in February. When Twitter launched a new milk-tea emoji in April, the movement received a boost and popularised the milk-tea meme. But the current symbolism of milk tea belies the drink’s complex past.

More here.

The Atlantic staff writer Ed Yong has won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. He was awarded journalism’s top honor for his defining coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and how America failed in its response to the virus. This is The Atlantic’s first Pulitzer Prize.

The Atlantic staff writer Ed Yong has won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. He was awarded journalism’s top honor for his defining coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and how America failed in its response to the virus. This is The Atlantic’s first Pulitzer Prize. When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of

When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of  Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant.

Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant. To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in

To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in  Mona Ali in Phenomenal World:

Mona Ali in Phenomenal World: Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar: Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed.

Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed. ROSENBAUM:

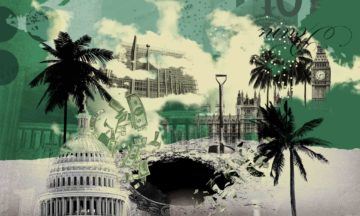

ROSENBAUM:  In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went.

In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went. Tyree’s answer to our present dilemma is weirdness, “cultivated eccentricity as an antidote to a world gone mad.” He proposes a Pynchonian counterforce, a ragged band of outsiders and misfits to resist all the orthodoxies of the day. Despite the polarization of the moment, both the left and the right feverishly engage in what Tyree terms timewashing: “[O]ur era’s signature creation of fake pasts that purport to cleanse history of its deep stains and recurring nightmares with the scented spray of propaganda.” Our “incapacity to live with the past in all its troubling complexity” poses a grave danger, he argues, and better fiction could be our salvation. He’s right, of course, but he also knows the unlikelihood of his solution: “Is it naïve to assert that we badly need dreamers like Pynchon to help us imagine a different future by reading through a different lens on our past?” Tyree answers his own question just three sentences later: “Yeah, that’s probably naïve.”

Tyree’s answer to our present dilemma is weirdness, “cultivated eccentricity as an antidote to a world gone mad.” He proposes a Pynchonian counterforce, a ragged band of outsiders and misfits to resist all the orthodoxies of the day. Despite the polarization of the moment, both the left and the right feverishly engage in what Tyree terms timewashing: “[O]ur era’s signature creation of fake pasts that purport to cleanse history of its deep stains and recurring nightmares with the scented spray of propaganda.” Our “incapacity to live with the past in all its troubling complexity” poses a grave danger, he argues, and better fiction could be our salvation. He’s right, of course, but he also knows the unlikelihood of his solution: “Is it naïve to assert that we badly need dreamers like Pynchon to help us imagine a different future by reading through a different lens on our past?” Tyree answers his own question just three sentences later: “Yeah, that’s probably naïve.” The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in

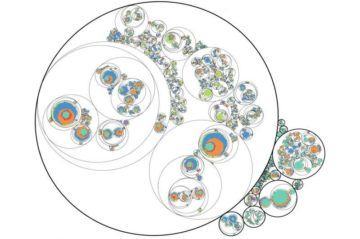

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in  It’s often cancer’s spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease’s most deadly risk. “And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of

It’s often cancer’s spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease’s most deadly risk. “And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of