David Berlinski in Inference Review:

Mishra was moved to republish these essays in their hardcover coffin, he remarks in his introduction, as a response to Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these essays were written before Brexit, the election of Trump, or the advent of COVID-19. They lack the degree of prophetic force that Mishra might think appropriate. The title itself reprises a phrase due to Reinhold Niebuhr: “[A]mong the lesser culprits of history,” Niebuhr wrote in 1959, “are the bland fanatics of western civilization who regard the highly contingent achievements of our culture as the final form and norm of human existence.”5 Mishra’s bland fanatics, treating things alphabetically, run from Martin Amis, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Francis Fukuyama to Steven Pinker, Bari Weiss, and Leon Wieseltier, all of them bland, none of them fanatical. Robert Blackwill, Dick Cheney, Richard Perle, Condoleezza Rice, Paul Wolfowitz, and Robert Zoellick are unaccountably beyond the beam of Mishra’s indignation. I would have thought that Cheney, at least, had the beady eyes characteristic of the born bland fanatic.

Mishra was moved to republish these essays in their hardcover coffin, he remarks in his introduction, as a response to Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of these essays were written before Brexit, the election of Trump, or the advent of COVID-19. They lack the degree of prophetic force that Mishra might think appropriate. The title itself reprises a phrase due to Reinhold Niebuhr: “[A]mong the lesser culprits of history,” Niebuhr wrote in 1959, “are the bland fanatics of western civilization who regard the highly contingent achievements of our culture as the final form and norm of human existence.”5 Mishra’s bland fanatics, treating things alphabetically, run from Martin Amis, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Francis Fukuyama to Steven Pinker, Bari Weiss, and Leon Wieseltier, all of them bland, none of them fanatical. Robert Blackwill, Dick Cheney, Richard Perle, Condoleezza Rice, Paul Wolfowitz, and Robert Zoellick are unaccountably beyond the beam of Mishra’s indignation. I would have thought that Cheney, at least, had the beady eyes characteristic of the born bland fanatic.

Two of the sixteen essays in this collection are devoted to single combat: Mishra vs. Niall Ferguson and Jordan Peterson. Fluffy and forgettable, they did succeed in provoking their subjects to a display of petulance. Ferguson threatened to sue Mishra for libel, and Peterson proposed to slap him silly should they happen to meet.

What a pity they did not.

More here.

Any system in which politicians represent geographical districts with boundaries chosen by the politicians themselves is vulnerable to gerrymandering: carving up districts to increase the amount of seats that a given party is expected to win. But even fairly-drawn boundaries can end up quite complex, so how do we know that a given map is unfairly skewed? Math comes to the rescue. We can ask whether the likely outcome of a given map is very unusual within the set of all possible reasonable maps. That’s a hard math problem, however — the set of all possible maps is pretty big — so we have to be clever to solve it. I talk with geometer Jordan Ellenberg about how ideas like random walks and Markov chains help us judge the fairness of political boundaries.

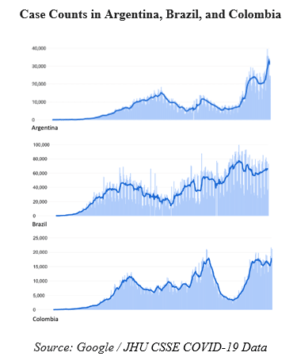

Any system in which politicians represent geographical districts with boundaries chosen by the politicians themselves is vulnerable to gerrymandering: carving up districts to increase the amount of seats that a given party is expected to win. But even fairly-drawn boundaries can end up quite complex, so how do we know that a given map is unfairly skewed? Math comes to the rescue. We can ask whether the likely outcome of a given map is very unusual within the set of all possible reasonable maps. That’s a hard math problem, however — the set of all possible maps is pretty big — so we have to be clever to solve it. I talk with geometer Jordan Ellenberg about how ideas like random walks and Markov chains help us judge the fairness of political boundaries. At the start of the year, there was reason to hope that we were beginning to see the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, the daily rate of new cases from the holiday surge began to drop precipitously, and the vaccine rollout accelerated soon thereafter. Although Europe lagged in the early months of 2021, there, too, the tide started to turn by April, as the pace of vaccination finally picked up.

At the start of the year, there was reason to hope that we were beginning to see the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, the daily rate of new cases from the holiday surge began to drop precipitously, and the vaccine rollout accelerated soon thereafter. Although Europe lagged in the early months of 2021, there, too, the tide started to turn by April, as the pace of vaccination finally picked up. But what does it mean when a building comes into existence as architecture only by accident—through contingency—under the erotic and transgressive conditions of an observer who was not supposed to be there seeing what was never supposed to be seen? There’s no usable lesson about “design” here, or urbanism, that the developer and his paid draughtsfolk might take away. No change to public policy or city codes. The experience of what we might think of as “the architectural,” in this instance, runs counter to every single intention behind the creation of this generic reflecting structure. It’s an experience born of incompleteness, of transience, like the spring itself.

But what does it mean when a building comes into existence as architecture only by accident—through contingency—under the erotic and transgressive conditions of an observer who was not supposed to be there seeing what was never supposed to be seen? There’s no usable lesson about “design” here, or urbanism, that the developer and his paid draughtsfolk might take away. No change to public policy or city codes. The experience of what we might think of as “the architectural,” in this instance, runs counter to every single intention behind the creation of this generic reflecting structure. It’s an experience born of incompleteness, of transience, like the spring itself. Neel was, to use a much-abused word, a humanist—and not only because she was a figurative painter. Unlike ponderously performative portraitists like Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, Neel did not objectify her subjects. She looked at them, and very often, they stared back at her. You might call her portraits a frank exchange of views. The gray-eyed woman who is the subject of “Elenka” (1936) could perform laser surgery with the intensity of her gaze. The expression on the face of Neel’s dying mother, bundled in a flannel robe, shrinking back and propped in a chair for “Last Sickness” (1953), is a lacerating blend of fear, reproach and shame. One of the two kids portrayed in “The Black Boys” (1967) is resigned, whereas the other, staring straight at the viewer, makes a challenge of his boredom.

Neel was, to use a much-abused word, a humanist—and not only because she was a figurative painter. Unlike ponderously performative portraitists like Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, Neel did not objectify her subjects. She looked at them, and very often, they stared back at her. You might call her portraits a frank exchange of views. The gray-eyed woman who is the subject of “Elenka” (1936) could perform laser surgery with the intensity of her gaze. The expression on the face of Neel’s dying mother, bundled in a flannel robe, shrinking back and propped in a chair for “Last Sickness” (1953), is a lacerating blend of fear, reproach and shame. One of the two kids portrayed in “The Black Boys” (1967) is resigned, whereas the other, staring straight at the viewer, makes a challenge of his boredom. By the time Republicans and centrist Democrats had united late last week to scold Representative Ilhan Omar for a tweet—one of the few pastimes that still draw the two parties together, and something those

By the time Republicans and centrist Democrats had united late last week to scold Representative Ilhan Omar for a tweet—one of the few pastimes that still draw the two parties together, and something those  E

E “Beauty,” David Hume held, “is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” If this were the case, then the human race’s radical disagreements over aesthetical evaluations would be reducible to harmless preferences. Inclined as we might be to enthusiastically espouse our favorite music as “beautiful,” honesty would require that we chasten our speech, opting for the more modest “beautiful for me,” or—better yet—“I like it,” and nothing more.

“Beauty,” David Hume held, “is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” If this were the case, then the human race’s radical disagreements over aesthetical evaluations would be reducible to harmless preferences. Inclined as we might be to enthusiastically espouse our favorite music as “beautiful,” honesty would require that we chasten our speech, opting for the more modest “beautiful for me,” or—better yet—“I like it,” and nothing more. Our ability to experience pleasure, as in the fundamental sensation of something being enjoyable or ‘nice’, is a product of what’s known as the ‘reward pathway’, a small but crucial

Our ability to experience pleasure, as in the fundamental sensation of something being enjoyable or ‘nice’, is a product of what’s known as the ‘reward pathway’, a small but crucial

As the origins of our current moral panic about “white supremacy” become more widely debated, we have an obvious problem: how to define the term “Critical Race Theory.” This was never going to be easy, since so much of the academic discourse behind the term is deliberately impenetrable, as it tries to disrupt and dismantle the Western concept of discourse itself. The sheer volume of jargon words, and their mutual relationships, along with the usual internal bitter controversies, all serve to sow confusion.

As the origins of our current moral panic about “white supremacy” become more widely debated, we have an obvious problem: how to define the term “Critical Race Theory.” This was never going to be easy, since so much of the academic discourse behind the term is deliberately impenetrable, as it tries to disrupt and dismantle the Western concept of discourse itself. The sheer volume of jargon words, and their mutual relationships, along with the usual internal bitter controversies, all serve to sow confusion. In many of our contemporary cultures, the realities of death feel unapproachable. Traditional grieving methods are routinely relegated to the margins, replaced by the medical promise of comforting objectivity. But for those of us confronted by the ebb and flow of complex emotions in the wake of death, the assurance of objectivity falls short. For Ioanna Sakellaraki, this evolving emotional storm, experienced head-on in the wake of her father’s death, is what prompted her to pursue a project on bereavement, finding ways to document the organic chaos that she describes as “the passageway into a liminal space of absence and presence.”

In many of our contemporary cultures, the realities of death feel unapproachable. Traditional grieving methods are routinely relegated to the margins, replaced by the medical promise of comforting objectivity. But for those of us confronted by the ebb and flow of complex emotions in the wake of death, the assurance of objectivity falls short. For Ioanna Sakellaraki, this evolving emotional storm, experienced head-on in the wake of her father’s death, is what prompted her to pursue a project on bereavement, finding ways to document the organic chaos that she describes as “the passageway into a liminal space of absence and presence.”