https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hv4HfLQGlw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5hv4HfLQGlw

Louis Bury at Art in America:

The most haunting thing about Maya Lin’s Ghost Forest is how ordinary it appears. On the central “Oval Lawn” in New York City’s well-trafficked Madison Square Park, the celebrated architect and sculptor has installed a stand of forty-nine bare cedar trees, resembling a dying woodland. The tall, toothpick-like conifers, pruned of branches at human height and entirely devoid of leaves, are meant to serve as portents of environmental devastation. But the quotidian park-going activities—sunbathing, picnicking, dog walking—taking place within and around these symbols of apocalypse suggest how easily people can adjust their baseline sense of normalcy.

The most haunting thing about Maya Lin’s Ghost Forest is how ordinary it appears. On the central “Oval Lawn” in New York City’s well-trafficked Madison Square Park, the celebrated architect and sculptor has installed a stand of forty-nine bare cedar trees, resembling a dying woodland. The tall, toothpick-like conifers, pruned of branches at human height and entirely devoid of leaves, are meant to serve as portents of environmental devastation. But the quotidian park-going activities—sunbathing, picnicking, dog walking—taking place within and around these symbols of apocalypse suggest how easily people can adjust their baseline sense of normalcy.

The bare trees were relocated from private land in the New Jersey Pine Barrens that was set to be cleared owing to saltwater inundation; their pocked and stripped bark is encrusted with pale gray lichen, which thrives in moist areas.

more here.

—After “Eclipse” by Rose Marie Cromwell

God holds my baby by her ankle

Dangles her from a cloud.

She is a thickened fawn

Contorting in his grip

Taut and winding over the scrubby trees below.

My baby came to me from the forest.

As she fell I think I caught her.

Yes, I caught her as she fell

Through the pines

And low-lying fever palm.

Dusk settled like a fog around our ankles.

God let go and I caught her.

A door opened in the forest ceiling.

She pushed it aside easily

All round arms

And brown curls

Still wet from the clouds.

The door crinkled like a brown tarp

In the wind.

She hovered there for a moment

Then her wings failed

And I dove.

We stand here now, darkness up to our chins.

I’m wading through the night forest

With her on my shoulders

Blinking at the starlight.

by Annik Adey-Babinski

from Poetry, June 2021

Isaac Chotiner in The New Yorker:

In his new book, “Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal,” George Packer writes that the United States is in a state of disrepair, brought about primarily by the fact that “inequality undermined the common faith that Americans need to create a successful multi-everything democracy.” The book opens with an essay on the state of the U.S. during the pandemic, and then offers sketches of four different visions of the country: Free America, of Reaganism; Smart America, of Silicon Valley and other professional élites; Real America, of Trumpist reaction; and Just America, of a new generation of leftists. “I don’t much want to live in the republic of any of them,” Packer writes. He proposes a different vision, which he thinks offers brighter possibilities, centered around the concept of equality and non-demagogic appeals to patriotism.

In his new book, “Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal,” George Packer writes that the United States is in a state of disrepair, brought about primarily by the fact that “inequality undermined the common faith that Americans need to create a successful multi-everything democracy.” The book opens with an essay on the state of the U.S. during the pandemic, and then offers sketches of four different visions of the country: Free America, of Reaganism; Smart America, of Silicon Valley and other professional élites; Real America, of Trumpist reaction; and Just America, of a new generation of leftists. “I don’t much want to live in the republic of any of them,” Packer writes. He proposes a different vision, which he thinks offers brighter possibilities, centered around the concept of equality and non-demagogic appeals to patriotism.

I recently spoke by phone with Packer, who is a staff writer at The Atlantic and was previously a staff writer at The New Yorker. He is also the author of the books “The Assassins’ Gate” and “The Unwinding.” During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed why Barack Obama failed to change the direction of the country, whether a more progressive form of patriotism is possible, and whether the cultural controversies roiling American institutions are an inevitable result of inequality.

Why did you decide to structure this book around four Americas?

We’ve all lived with the red-blue division for about twenty years. And it’s true. We are divided that way. Every passing year makes that clearer. But I felt that in the last few years, politically and culturally, things have happened that showed that there are divisions within, as well as between, those two big blocks of Americans. The basic division that I began to see begins with libertarianism, which I call Free America, which is Reagan’s America. And this is really the story of my adult life, from the late nineteen-seventies onward. It’s been the most dominant narrative in our society. And it says, “We’re all individuals.” We all have a chance to make it. The best way to make it is to get government out of the way and to cut taxes and deregulate and set us free in order to use our industry and talent to make something new. And that was a really potent story that Reagan told, and that the Republican Party lived by for decades, and to some extent still does.

More here.

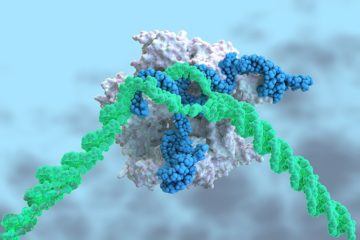

Heidi Ledford in Nature:

Preliminary results from a landmark clinical trial suggest that CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing can be deployed directly into the body to treat disease. The study is the first to show that the technique can be safe and effective if the CRISPR–Cas9 components — in this case targeting a protein that is made mainly in the liver — are infused into the bloodstream. In the trial, six people with a rare and fatal condition called transthyretin amyloidosis received a single treatment with the gene-editing therapy. All experienced a drop in the level of a misshapen protein associated with the disease. Those who received the higher of two doses tested saw levels of the protein, called TTR, decline by an average of 87%.

Preliminary results from a landmark clinical trial suggest that CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing can be deployed directly into the body to treat disease. The study is the first to show that the technique can be safe and effective if the CRISPR–Cas9 components — in this case targeting a protein that is made mainly in the liver — are infused into the bloodstream. In the trial, six people with a rare and fatal condition called transthyretin amyloidosis received a single treatment with the gene-editing therapy. All experienced a drop in the level of a misshapen protein associated with the disease. Those who received the higher of two doses tested saw levels of the protein, called TTR, decline by an average of 87%.

The treatment was developed by Intellia Therapeutics of Cambridge, Massachusetts and Regeneron of Tarrytown, New York. They published the trial results in The New England Journal of Medicine1 and presented them at an online meeting of the Peripheral Nerve Society on 26 June. Previous results from CRISPR–Cas9 clinical trials have suggested that the technique can be used in cells that have been removed from the body. The cells are edited and then reinfused back into study participants. But to be able to edit genes directly in the body would open the door to treating a wider range of diseases. “It’s an important moment for the field,” says Daniel Anderson, a biomedical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “It’s a whole new era of medicine.”

More here.

Chad Orzel in Forbes:

A long time ago, when I was around the age my kids are now— so if you were to ask them, that’d put it well after the dinosaurs but slightly before woolly mammoths— I had to write a book report about a biography. For whatever reason, I ended up picking Enrico Fermi, a scientist who was featured in exactly one book in the elementary school library, a choice that maybe foreshadowed my eventual career. A few details of that have stuck with me ever since: Fermi getting reprimanded by Oppenheimer for taking bets on whether the Trinity test would ignite the atmosphere, Fermi estimating the size of the blast by dropping pieces of paper, and, weirdly, Fermi mocking signs with Fascist slogans back in Italy by shouting “Burma Shave!” when driving past them (probably because I had to get my parents to explain the joke). I was a little hazy on what, exactly, he contributed to physics, but he definitely made an impression as both an important scientist and a colorful character.

A long time ago, when I was around the age my kids are now— so if you were to ask them, that’d put it well after the dinosaurs but slightly before woolly mammoths— I had to write a book report about a biography. For whatever reason, I ended up picking Enrico Fermi, a scientist who was featured in exactly one book in the elementary school library, a choice that maybe foreshadowed my eventual career. A few details of that have stuck with me ever since: Fermi getting reprimanded by Oppenheimer for taking bets on whether the Trinity test would ignite the atmosphere, Fermi estimating the size of the blast by dropping pieces of paper, and, weirdly, Fermi mocking signs with Fascist slogans back in Italy by shouting “Burma Shave!” when driving past them (probably because I had to get my parents to explain the joke). I was a little hazy on what, exactly, he contributed to physics, but he definitely made an impression as both an important scientist and a colorful character.

Possibly because of that long-ago assignment, “Popular biography of Fermi” has long been on my mental list of potential future book projects. So I was mildly disappointed a few years ago when I learned that David Schwartz had written The Last Man Who Knew Everything: The Life And Times Of Enrico Fermi, Father Of The Nuclear Age (only mildly, because it’s a long list of potential projects).

More here.

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Depending on who you listen to, quantum computers are either the biggest technological change coming down the road or just another overhyped bubble. Today we’re talking with a good person to listen to: John Preskill, one of the leaders in modern quantum information science. We talk about what a quantum computer is and promising technologies for actually building them. John emphasizes that quantum computers are tailor-made for simulating the behavior of quantum systems like molecules and materials; whether they will lead to breakthroughs in cryptography or optimization problems is less clear. Then we relate the idea of quantum information back to gravity and the emergence of spacetime. (If you want to build and run your own quantum algorithm, try the IBM Quantum Experience.)

Depending on who you listen to, quantum computers are either the biggest technological change coming down the road or just another overhyped bubble. Today we’re talking with a good person to listen to: John Preskill, one of the leaders in modern quantum information science. We talk about what a quantum computer is and promising technologies for actually building them. John emphasizes that quantum computers are tailor-made for simulating the behavior of quantum systems like molecules and materials; whether they will lead to breakthroughs in cryptography or optimization problems is less clear. Then we relate the idea of quantum information back to gravity and the emergence of spacetime. (If you want to build and run your own quantum algorithm, try the IBM Quantum Experience.)

More here.

Elie Mystal in The Nation:

The law has failed Britney Spears. The nearly 40-year-old celebrity has been locked in a “conservatorship”—which is the state of California’s word for a “legal guardianship” designed for the very old, very young, or mentally incapacitated—for 13 years, against her will. That conservatorship, controlled by her father, again, against her will, has been allowed to control Spears’s life in minute detail—including allegedly forcing unwanted birth control upon her—and none of the lawyers or judges involved has done a damn thing to stop it. Spears appeared in court, via telephone, this week to voice her objections to her continued conservatorship, and her story should lead to immediate lawmaking and change.

The law has failed Britney Spears. The nearly 40-year-old celebrity has been locked in a “conservatorship”—which is the state of California’s word for a “legal guardianship” designed for the very old, very young, or mentally incapacitated—for 13 years, against her will. That conservatorship, controlled by her father, again, against her will, has been allowed to control Spears’s life in minute detail—including allegedly forcing unwanted birth control upon her—and none of the lawyers or judges involved has done a damn thing to stop it. Spears appeared in court, via telephone, this week to voice her objections to her continued conservatorship, and her story should lead to immediate lawmaking and change.

Believe me, I’m as surprised as anybody to find myself on this particular hill.

I’ll admit that the #FreeBritney movement—the group of fans who have been reading Spears’s Instagram page and bringing attention to her conservatorship—looked more like frenzied celebrity worshipers than legal reformers to me. But I think that I was wrong.

More here.

Nicholas Brown at nonsite:

The two dialectical modes—call them determinate and indeterminate negation—are unevenly distributed throughout Fried’s work. (There is probably more to be said about that.) From the standpoint of Jacques-Louis David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women, the approach he had taken in Oath of the Horatii just over a decade earlier appears as superseded. But while Rineke Dijkstra’s bathers mobilize facingness and an awareness of the camera, there is no sense in Fried’s interpretation of them that they supersede, negate, or critique Andreas Gursky’s preference for figures that are oblivious to the camera or viewed from behind. One can imagine formulating a claim that Dijkstra’s bathers do in fact represent an advance over some of Gursky’s pictures—a deepening or reduplication of the photographic tension between automatism and intention—but that would be an additional claim, beyond the essentially dialectical one that the two photographers are working in the context of a self-critical normative or institutional field; that both artists are engaged in confronting a problem or contradiction that is understood to be constitutive of photography itself, a “hidden motor” of dialectical development (AO 50). Dialectical movement can be expansive or lateral—even rhizomatic (“well-grubbed”)—as well as determinately directional.

The two dialectical modes—call them determinate and indeterminate negation—are unevenly distributed throughout Fried’s work. (There is probably more to be said about that.) From the standpoint of Jacques-Louis David’s Intervention of the Sabine Women, the approach he had taken in Oath of the Horatii just over a decade earlier appears as superseded. But while Rineke Dijkstra’s bathers mobilize facingness and an awareness of the camera, there is no sense in Fried’s interpretation of them that they supersede, negate, or critique Andreas Gursky’s preference for figures that are oblivious to the camera or viewed from behind. One can imagine formulating a claim that Dijkstra’s bathers do in fact represent an advance over some of Gursky’s pictures—a deepening or reduplication of the photographic tension between automatism and intention—but that would be an additional claim, beyond the essentially dialectical one that the two photographers are working in the context of a self-critical normative or institutional field; that both artists are engaged in confronting a problem or contradiction that is understood to be constitutive of photography itself, a “hidden motor” of dialectical development (AO 50). Dialectical movement can be expansive or lateral—even rhizomatic (“well-grubbed”)—as well as determinately directional.

more here.

Hephzibah Anderson in The Guardian:

“Let’s complain”, exhorts Lucy Ellmann in a preface to her first essay collection, Things Are Against Us. And complain she does, though the verb barely seems adequate for the atrabilious, freewheeling fury that spills from its pages. Aimed at everything from air travel to zips, genre writing to men (above all, men), her ire is matched only by an irrepressible comic impulse, from which bubbles forth kitsch puns, wisecracking whimsy and one-liners both bawdy and venomous. As she explains: “In times of pestilence, my fancy turns to shticks.” Goofiness notwithstanding, Ellmann is complaining only to the extent that the sans-culottes grumbled about goings-on at Versailles. She’s out to foment revolution, and this book is nothing less than a manifesto.

“Let’s complain”, exhorts Lucy Ellmann in a preface to her first essay collection, Things Are Against Us. And complain she does, though the verb barely seems adequate for the atrabilious, freewheeling fury that spills from its pages. Aimed at everything from air travel to zips, genre writing to men (above all, men), her ire is matched only by an irrepressible comic impulse, from which bubbles forth kitsch puns, wisecracking whimsy and one-liners both bawdy and venomous. As she explains: “In times of pestilence, my fancy turns to shticks.” Goofiness notwithstanding, Ellmann is complaining only to the extent that the sans-culottes grumbled about goings-on at Versailles. She’s out to foment revolution, and this book is nothing less than a manifesto.

It begins gently enough with the title essay, one of just three not to have already been published elsewhere. Ellmann is tormented by the “conspiratorial manoeuvrings” of inanimate objects. Socks race to get away from her, and pens, credit cards and lemons hurry after them. Paper cuts, soap slips and fitted sheets never do fit. It’s the kind of rogue anthropomorphism at which Dickens, one of her favourite writers, excels, but what really unnerves her is the sense that if these things have it in them to become so hostile, then what potential slights might be delivered by those we’ve really wronged – the vegetables we chow down on, the animals?

Humans are not, in fact, the innocent party here, but the unity of Ellmann’s guilty “we” evaporates in the next essay, Three Strikes, which splits the human race into them and us – them being men, us being women – and more or less keeps it that way until the book’s end. Its message – one that’s rooted in her 2013 novel Mimi, and resounds throughout – is that men have made such a colossal dog’s dinner of running the world, it’s only reasonable for women to take over. She has plenty of ideas for how we’ll rout the patriarchy, including strikes (we must refuse all domestic labour, work and, Lysistrata-style, sex with men) and the compulsory redistribution of male wealth (“yanking cash out of male hands is a humanitarian act”). Matriarchal socialism, she believes, is our sole hope if we’re to save humanity and avert ecological catastrophe.

More here.

Sasha Frere-Jones at Poetry Magazine:

In “Visible Republic,” his essay on Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Robbins extracts himself from the pro/con squad and tries to isolate the nature of the songwriter (rather than isolate the most literary thing about Dylan because what would that be?). “That’s it, that’s the thing—Dylan isn’t words,” Robbins writes. “He’s words plus [Robbie] Robertson’s uncanny awk, drummer Levon Helm’s cephalopodic clatter, the thin, wild mercury of his voice.” Meaning, one thinks, that by all means win some prizes, who cares, but don’t make one form do another’s work. This exhibits the generosity in both Robbins’s poems and essays. The glittering trash of the world needs itemizing but not sorting. His essay on Charles Simic, whom Robbins loves, begins free of hagiography: “How to write a Charles Simic poem: Go to a café. Wait for something weird to happen. Record mouse activity. Repeat as necessary. (For ‘mouse,’ feel free to substitute ‘cat,’ ‘roach,’ ‘rat,’ ‘chicken,’ ‘donkey,’ etc.)” He notes the “little astonishments” of early Simic and then maps the older poet’s journey into soft routine, in which Simic writes “banal snapshots bewildering in their literality.”

In “Visible Republic,” his essay on Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Robbins extracts himself from the pro/con squad and tries to isolate the nature of the songwriter (rather than isolate the most literary thing about Dylan because what would that be?). “That’s it, that’s the thing—Dylan isn’t words,” Robbins writes. “He’s words plus [Robbie] Robertson’s uncanny awk, drummer Levon Helm’s cephalopodic clatter, the thin, wild mercury of his voice.” Meaning, one thinks, that by all means win some prizes, who cares, but don’t make one form do another’s work. This exhibits the generosity in both Robbins’s poems and essays. The glittering trash of the world needs itemizing but not sorting. His essay on Charles Simic, whom Robbins loves, begins free of hagiography: “How to write a Charles Simic poem: Go to a café. Wait for something weird to happen. Record mouse activity. Repeat as necessary. (For ‘mouse,’ feel free to substitute ‘cat,’ ‘roach,’ ‘rat,’ ‘chicken,’ ‘donkey,’ etc.)” He notes the “little astonishments” of early Simic and then maps the older poet’s journey into soft routine, in which Simic writes “banal snapshots bewildering in their literality.”

more here.

Robert Bazell in Nautilus:

Three decades ago, a small group from within the AIDS activist organization ACT UP changed the course of medicine in the United States. They employed what they called “the outside/inside strategy.” The activists staged large, noisy demonstrations outside the Food and Drug Administration and other federal government agencies, demanding an acceleration of the drug-approval process. Others learned the minutiae of the science and worked quietly with receptive bureaucrats, bringing the patient’s perspective to the table toward the same goal of faster drug approval. These were desperate young people dying from a new disease for which there were few treatments and no cure. At first, federal bureaucrats and drug companies resisted, but eventually more AIDS drugs became available.

Three decades ago, a small group from within the AIDS activist organization ACT UP changed the course of medicine in the United States. They employed what they called “the outside/inside strategy.” The activists staged large, noisy demonstrations outside the Food and Drug Administration and other federal government agencies, demanding an acceleration of the drug-approval process. Others learned the minutiae of the science and worked quietly with receptive bureaucrats, bringing the patient’s perspective to the table toward the same goal of faster drug approval. These were desperate young people dying from a new disease for which there were few treatments and no cure. At first, federal bureaucrats and drug companies resisted, but eventually more AIDS drugs became available.

The push by AIDS activists for an effective treatment was a breakthrough in the medical industry. It showed the power of a grassroots movement to spur the government and Big Pharma to action. But it had a dangerous and lasting side effect. Over the ensuing decades, pharmaceutical companies learned that with the backing of patient advocacy groups, they could get more drugs approved more quickly with less robust data. The drug-approval process slackened considerably, and the result has been many products with minimal effectiveness generating enormous profits.

This trend, according to scientists, reached its nadir with the recent approval of Aduhelm (also known by its generic name aducanumab), a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease from the biotech company Biogen. The F.D.A. approved the treatment following intense lobbying by the Alzheimer’s Association patient group. A recent report from the Alzheimer’s Association reveals that it received a $275,000 donation from Biogen in 2020. Eisai, a Japanese company that partnered in the development of the drug, gave $250,000 in 2020. The Association also received large donations from other companies hoping to bring their own, similar, Alzheimer’s drugs to market. The F.D.A.’s decision is “abominable,” said Peter B. Bach of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, an expert on drug policy and pricing. He told me the decision will lead to companies and lobbyists “acting as the arbiters of what is safe and effective,” and a health care system that is “more opaque, more inequitable, and deeply subject to conflicting financial and political interests.” Biogen originally declared the two critical Phase III trials of the drug failures. In fact, the company stopped the trials, and its C.E.O. Michel Vounatsos said, in a statement, “This disappointing news confirms the complexity of treating Alzheimer’s disease and the need to further advance knowledge in neuroscience.”

More here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WqNkjNf6ceI

We came down from the Chiricahua Mountains,

went even closer to the border, hiked rocky

hillsides off-road, spotted a five-striped sparrow,

so fine, yet overshadowed by the rotor noise

of the sporadic helicopter overhead. Our guide

said to hold up our binoculars, let them know

we were only birdwatchers, and we complied,

having already passed trucks stopped in the desert,

unloading ATVs that armed and armored men

rode off. Earlier, I’d asked about the tethered

gray dirigibles in the otherwise cloudless sky,

was told they were platforms for surveillance.

Overseas for decades, much of it in conflict

areas, I’d never seen such heavy arms, such war

materiel in my country, not outside military

bases. The border sun was bright, our pace

slow, but still, I had to close my eyes, breath

caught with twinges of fear and vertigo, darkness

in waves like a mirage, waves of sparrows fallen

by vertiginous plunge or slow slump, in the desert,

unseen by any person, me among them.

by Sandra Gustin

from The Poetry Foundation

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Is there any bit of popular philosophical wisdom more useless than the pseudo-Epictetian injunction to “live every day as if it were your last”? If today were my last, I certainly would not have just impulse-ordered an introductory grammar of Lithuanian. Much of what I do each day, in fact, is premised on the expectation that I will continue to do a little bit more of it the day after, and then the day after that, until I accomplish what is intrinsically a massively multi-day project. If I’ve only got one more day to do my stuff, well, the projects I reserve for that special day are hardly going to be the same ones (Lithuanian, Travis-style thumb-picking) by which I project myself, by which I throw myself towards the future. If today were my last day, I might still find time to churn out a quick ‘stack (no more than 5000 words) thanking you all for your loyal readership. But the noun-declension systems of the Baltic languages would probably be postponed for another life.

Is there any bit of popular philosophical wisdom more useless than the pseudo-Epictetian injunction to “live every day as if it were your last”? If today were my last, I certainly would not have just impulse-ordered an introductory grammar of Lithuanian. Much of what I do each day, in fact, is premised on the expectation that I will continue to do a little bit more of it the day after, and then the day after that, until I accomplish what is intrinsically a massively multi-day project. If I’ve only got one more day to do my stuff, well, the projects I reserve for that special day are hardly going to be the same ones (Lithuanian, Travis-style thumb-picking) by which I project myself, by which I throw myself towards the future. If today were my last day, I might still find time to churn out a quick ‘stack (no more than 5000 words) thanking you all for your loyal readership. But the noun-declension systems of the Baltic languages would probably be postponed for another life.

More here.

Bhaskar Sunkara in The Guardian:

It’s a nightmare we should have seen coming. In Germany, nuclear power formed around a third of the country’s power generation in 2000, when a Green party-spearheaded campaign managed to secure the gradual closure of plants, citing health and safety concerns. Last year, that share fell to 11%, with all remaining stations scheduled to close by next year. A recent paper found that the last two decades of phased nuclear closures led to an increase in CO2 emissions of 36.3 megatons a year – with the increased air pollution potentially killing 1,100 people annually.

It’s a nightmare we should have seen coming. In Germany, nuclear power formed around a third of the country’s power generation in 2000, when a Green party-spearheaded campaign managed to secure the gradual closure of plants, citing health and safety concerns. Last year, that share fell to 11%, with all remaining stations scheduled to close by next year. A recent paper found that the last two decades of phased nuclear closures led to an increase in CO2 emissions of 36.3 megatons a year – with the increased air pollution potentially killing 1,100 people annually.

Like New York, Germany coupled its transition away from nuclear power with a pledge to spend more aggressively on renewables. Yet the country’s first plant closures meant carbon emissions actually increased, as the production gap was immediately filled through the construction of new coal plants. Similarly, in New York the gap will be filled in part by the construction of three new gas plants.

More here.

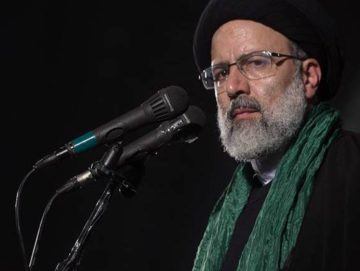

Abbas Milani in Project Syndicate:

Iran’s presidential election on June 18 was the most farcical in the history of the Islamic regime – even more so than the 2009 election, often called an “electoral coup.” It was less an election than a chronicle of a death foretold – the death of what little remained of the constitution’s republican principles. But, in addition to being the most farcical, the election may be the Islamic Republic’s most consequential.

Iran’s presidential election on June 18 was the most farcical in the history of the Islamic regime – even more so than the 2009 election, often called an “electoral coup.” It was less an election than a chronicle of a death foretold – the death of what little remained of the constitution’s republican principles. But, in addition to being the most farcical, the election may be the Islamic Republic’s most consequential.

The winner, Sayyid Ebrahim Raisi, is credibly accused of crimes against humanity for his role in killing some 4,000 dissidents three decades ago. Amnesty International has already called for him to be investigated for these crimes. Asked about the accusation, the new president-elect replied in a way that would have made even George Orwell blush, insisting that he should be praised for his defense of human rights in those murders.

Never has such a motley crew been chosen to act as a foil for its favored candidate. The regime mobilized all of its forces to ensure a big turnout for Raisi, who until the election was Iran’s chief justice. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei decreed voting a religious duty, and casting a blank ballot a sin, while his clerical allies condemned advocates of a boycott as heretics.

More here.

Philip Oltermann in The Guardian:

The name of the initiative was Project Cassandra: for the next two years, university researchers would use their expertise to help the German defence ministry predict the future.

The name of the initiative was Project Cassandra: for the next two years, university researchers would use their expertise to help the German defence ministry predict the future.

The academics weren’t AI specialists, or scientists, or political analysts. Instead, the people the colonels had sought out in a stuffy top-floor room were a small team of literary scholars led by Jürgen Wertheimer, a professor of comparative literature with wild curls and a penchant for black roll-necks.

More here.