Megan Pillow in Guernica:

The first time I saw the Breonna Taylor memorial was on a livestream. It was summer of 2020, and I watched a small team of people at Injustice Square shake out tarps and cover the collection of paintings and signs to protect them from rain. The second time I saw it was in person. I walked around it, noticed the nameplates inscribed with the names of the other Black men and women killed by police encircling its edges. There was one painting of Taylor that was massive, vibrant; a sheen of purple glistened in her hair, and a small jewel glittered in her nose. At its base were poster boards proclaiming “Justice for Bre” and “She was asleep.” Around me, protestors shouted out some of those same lines through their masks.

The first time I saw the Breonna Taylor memorial was on a livestream. It was summer of 2020, and I watched a small team of people at Injustice Square shake out tarps and cover the collection of paintings and signs to protect them from rain. The second time I saw it was in person. I walked around it, noticed the nameplates inscribed with the names of the other Black men and women killed by police encircling its edges. There was one painting of Taylor that was massive, vibrant; a sheen of purple glistened in her hair, and a small jewel glittered in her nose. At its base were poster boards proclaiming “Justice for Bre” and “She was asleep.” Around me, protestors shouted out some of those same lines through their masks.

In Breonna Taylor’s city, which is also my city, protestors have gathered at Injustice Square regularly since May 28, 2020. Beginning just three days after George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, they occupied that small square of land. Through the summer of 2020 and into the fall, they showed up every day—even after another Louisville resident, beloved local chef and entrepreneur David McAtee, was gunned down by the National Guard just days after Floyd’s death and his body left in the street for hours. Every day, even through colder months that saw protest leaders Travis Nagdy and Kris Smith shot down in the street, becoming part of Louisville’s record 173 homicides last year.

After my second visit to the square, I felt haunted by a question I didn’t know how to ask. I worried that the ink on the posters would run in a hard rain, that people’s memories would degrade. Most of all, I was terrified that the police would attack the very people desperately fighting for justice and preserving Taylor’s memory. At a loss, I turned to Google and typed: How do we save everyone, everything?

A more generative question is this: How will we remember 2020? In the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, as protests against racial injustice and police violence spread across the country, there was more than one Saturday night where I found myself Googling “pandemic archives.” Enraged and lonely and trying to make sense of why some stories are preserved and others are overlooked, I wanted to know what preservation work was already happening and, crucially, who was doing it. I wanted to know what stories and objects they deemed important enough to save, and what strategies, rationales, and systems they were using to capture them. What I found was a range of organizations attempting to chronicle a monumental and disastrous year while it was still underway.

In between a couple of links to archives of the flu pandemic of 1918 and a host of sites banking medical and scientific information about the virus were a number of crowdsourced projects, some localized, some international.

More here.

The first time I saw the Breonna Taylor memorial was on a livestream. It was summer of 2020, and I watched a small team of people at Injustice Square shake out tarps and cover the collection of paintings and signs to protect them from rain. The second time I saw it was in person. I walked around it, noticed the nameplates inscribed with the names of the other Black men and women killed by police encircling its edges. There was one painting of Taylor that was massive, vibrant; a sheen of purple glistened in her hair, and a small jewel glittered in her nose. At its base were poster boards proclaiming “Justice for Bre” and “She was asleep.” Around me, protestors shouted out some of those same lines through their masks.

The first time I saw the Breonna Taylor memorial was on a livestream. It was summer of 2020, and I watched a small team of people at Injustice Square shake out tarps and cover the collection of paintings and signs to protect them from rain. The second time I saw it was in person. I walked around it, noticed the nameplates inscribed with the names of the other Black men and women killed by police encircling its edges. There was one painting of Taylor that was massive, vibrant; a sheen of purple glistened in her hair, and a small jewel glittered in her nose. At its base were poster boards proclaiming “Justice for Bre” and “She was asleep.” Around me, protestors shouted out some of those same lines through their masks. Researchers developing the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine have identified biomarkers that can help to predict whether someone will be protected by the jab they receive. The team at the University of Oxford, UK, identified a ‘correlate of protection’ from the immune responses of trial participants — the first found by any COVID-19 vaccine developer. Identifying such blood markers, scientists say, will improve existing vaccines and speed the development of new ones by reducing the need for costly large-scale efficacy trials.

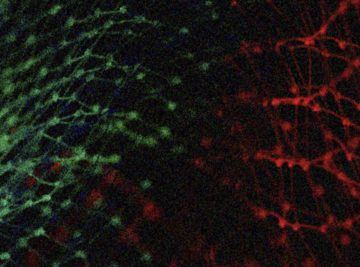

Researchers developing the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine have identified biomarkers that can help to predict whether someone will be protected by the jab they receive. The team at the University of Oxford, UK, identified a ‘correlate of protection’ from the immune responses of trial participants — the first found by any COVID-19 vaccine developer. Identifying such blood markers, scientists say, will improve existing vaccines and speed the development of new ones by reducing the need for costly large-scale efficacy trials. “Neuroaesthetics can perhaps be understood in the Duchampian sense,” he claimed in a 2004 interview. “Neuroscience is a readymade, which is recontextualized out from its original context as a scientific-based paradigm into one that is aesthetically based.” He pointed to Conceptualists like Dan Graham and Sol LeWitt as precursors of a later generation of artists who would act as mediators between an increasingly technologized and monetized society and its hyperactive visual culture. Neuroaesthetics endeavored not to produce a synthesis of neuroscience and aesthetics, but rather to estrange the former from normal usage—much as Duchamp did the bicycle wheel and bottle rack—and reenvision in a more psychodynamic capacity its tools for mapping cognitive categories such as color, memory, and spatial relationships, in order to reveal, in Neidich’s words, “the idea of becoming brain.”

“Neuroaesthetics can perhaps be understood in the Duchampian sense,” he claimed in a 2004 interview. “Neuroscience is a readymade, which is recontextualized out from its original context as a scientific-based paradigm into one that is aesthetically based.” He pointed to Conceptualists like Dan Graham and Sol LeWitt as precursors of a later generation of artists who would act as mediators between an increasingly technologized and monetized society and its hyperactive visual culture. Neuroaesthetics endeavored not to produce a synthesis of neuroscience and aesthetics, but rather to estrange the former from normal usage—much as Duchamp did the bicycle wheel and bottle rack—and reenvision in a more psychodynamic capacity its tools for mapping cognitive categories such as color, memory, and spatial relationships, in order to reveal, in Neidich’s words, “the idea of becoming brain.” Bridges connect us – and they have since the beginning of time, all the way back to the very first bridge, the rainbow. They connect us geographically, strategically, metaphorically, lyrically (if that last seems a stretch, think of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters”). Now we have a book to explain all sorts of bridges to us, thanks to UCLA author

Bridges connect us – and they have since the beginning of time, all the way back to the very first bridge, the rainbow. They connect us geographically, strategically, metaphorically, lyrically (if that last seems a stretch, think of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters”). Now we have a book to explain all sorts of bridges to us, thanks to UCLA author  “What is the use of stories that aren’t even true?” Haroun asks his father in Salman Rushdie’s delightful and inexplicably underrated crossover novel. Rushdie suggests the issue it raises, the relationship between the “world of imagination and the so-called real world”, has occupied most of his writing life.

“What is the use of stories that aren’t even true?” Haroun asks his father in Salman Rushdie’s delightful and inexplicably underrated crossover novel. Rushdie suggests the issue it raises, the relationship between the “world of imagination and the so-called real world”, has occupied most of his writing life. The Universal Approximation Theorem is, very literally, the theoretical foundation of why neural networks work. Put simply, it states that a neural network with one hidden layer containing a sufficient but finite number of neurons can approximate any continuous function to a reasonable accuracy, under certain conditions for activation functions (namely, that they must be sigmoid-like).

The Universal Approximation Theorem is, very literally, the theoretical foundation of why neural networks work. Put simply, it states that a neural network with one hidden layer containing a sufficient but finite number of neurons can approximate any continuous function to a reasonable accuracy, under certain conditions for activation functions (namely, that they must be sigmoid-like). The

The  T

T When European naturalists explored the plants of the New World in the sixteenth century, they tended to relate new species to better-known plants whenever they could. Sarsaparilla is a case in point. Smilax species found in America were recognized as variants of Smilax aspera and therefore also began to be called sarsaparilla. Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588) described different kinds of American sarsaparilla in his work Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (1565). His descriptions carried a commercial touch. For instance, he tried to convince his readers that the whitish sarsaparilla from Honduras was better than the black variety from Mexico. Similarly, he aimed to embed the new American kinds of sarsaparilla in the traditional framework of European medicine. When American sarsaparilla began to be used in European medicine around 1545, physicians first administered it as a broth to be taken in the morning, the same way as it was used by Native Americans at the time. Monardes, however, argued that it should be given in a syrup, a conventional mode of administration for his European readers.

When European naturalists explored the plants of the New World in the sixteenth century, they tended to relate new species to better-known plants whenever they could. Sarsaparilla is a case in point. Smilax species found in America were recognized as variants of Smilax aspera and therefore also began to be called sarsaparilla. Nicolás Monardes (1493–1588) described different kinds of American sarsaparilla in his work Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (1565). His descriptions carried a commercial touch. For instance, he tried to convince his readers that the whitish sarsaparilla from Honduras was better than the black variety from Mexico. Similarly, he aimed to embed the new American kinds of sarsaparilla in the traditional framework of European medicine. When American sarsaparilla began to be used in European medicine around 1545, physicians first administered it as a broth to be taken in the morning, the same way as it was used by Native Americans at the time. Monardes, however, argued that it should be given in a syrup, a conventional mode of administration for his European readers. A painful pattern repeats itself throughout America: A Black person is killed by police officers, protests ensue, and police are brought in to stifle the demonstrations. Most of the time, the protests against racial injustice are peaceful, but occasionally violence breaks out. Meanwhile, politicians do little to prevent the cycle from continuing.

A painful pattern repeats itself throughout America: A Black person is killed by police officers, protests ensue, and police are brought in to stifle the demonstrations. Most of the time, the protests against racial injustice are peaceful, but occasionally violence breaks out. Meanwhile, politicians do little to prevent the cycle from continuing. Proteins have been quietly taking over our lives since the COVID-19 pandemic began. We’ve been living at the whim of the virus’s so-called “spike” protein, which has mutated dozens of times to create increasingly deadly variants. But the truth is, we have always been ruled by proteins. At the cellular level, they’re responsible for pretty much everything.

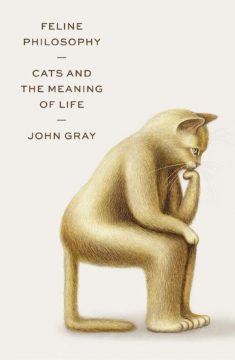

Proteins have been quietly taking over our lives since the COVID-19 pandemic began. We’ve been living at the whim of the virus’s so-called “spike” protein, which has mutated dozens of times to create increasingly deadly variants. But the truth is, we have always been ruled by proteins. At the cellular level, they’re responsible for pretty much everything. Academia puts scholars through the wringer. Few — very few, in fact — come out willing or even able to express complex ideas in ways appealing to non-academics. John Gray is one of those rare intellectuals.

Academia puts scholars through the wringer. Few — very few, in fact — come out willing or even able to express complex ideas in ways appealing to non-academics. John Gray is one of those rare intellectuals. The most basic tenet undergirding neoliberal economics is that free market capitalism—or at least some close approximation to it—is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. On this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes: big government spending and heavy regulations are simply less effective.

The most basic tenet undergirding neoliberal economics is that free market capitalism—or at least some close approximation to it—is the only effective framework for delivering widely shared economic well-being. On this view, only free markets can increase productivity and average living standards while delivering high levels of individual freedom and fair social outcomes: big government spending and heavy regulations are simply less effective.