Morgan Meis in The Easel:

The painting is known as Woman in Grey Reclining. It was painted in 1879. It depicts a woman in a lovely dress reclining on a couch. Does she have a white flower on the left strap of her dress? Maybe. Probably. We cannot be completely sure. That’s because much of the detail in the painting is only hinted at by the brushwork. A few dabs of white paint here. A few daubs of grey over there. A stroke of black across the neck, giving us the sense of a choker. We’ve come to call this kind of painting impressionist. The term was originally meant as an insult. But it stuck and became a moniker of pride, as often happens with insults.

The painting is known as Woman in Grey Reclining. It was painted in 1879. It depicts a woman in a lovely dress reclining on a couch. Does she have a white flower on the left strap of her dress? Maybe. Probably. We cannot be completely sure. That’s because much of the detail in the painting is only hinted at by the brushwork. A few dabs of white paint here. A few daubs of grey over there. A stroke of black across the neck, giving us the sense of a choker. We’ve come to call this kind of painting impressionist. The term was originally meant as an insult. But it stuck and became a moniker of pride, as often happens with insults.

I’m interested in a very specific part of this painting. It’s an area of paint in the middle right side of the painting (from the viewer’s perspective), the smudgy area of white and grey over the top of the couch just beyond the woman’s arm. Do you see it? What is that smear doing there? It’s not part of the couch. And it’s not part of the woman’s dress. Nor does it belong to the wall. It’s quite disconcerting when you really focus on it.

More here.

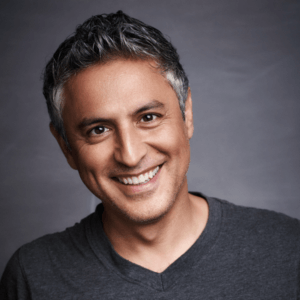

Religion is an important part of the lives of billions of people around the world, but what religious belief actually amounts to can vary considerably from person to person. Some believe in an anthropomorphic, judgmental God; others conceive of God as more transcendent and conceptual; some are animists who attribute spiritual essence to creatures and objects; and many more. I talk with writer and religious scholar Reza Aslan about his view of religion as a vocabulary constructed by human beings to express a connection with something beyond the physical world — why one might think that, and what it implies about how we should go about living our lives.

Religion is an important part of the lives of billions of people around the world, but what religious belief actually amounts to can vary considerably from person to person. Some believe in an anthropomorphic, judgmental God; others conceive of God as more transcendent and conceptual; some are animists who attribute spiritual essence to creatures and objects; and many more. I talk with writer and religious scholar Reza Aslan about his view of religion as a vocabulary constructed by human beings to express a connection with something beyond the physical world — why one might think that, and what it implies about how we should go about living our lives. I’m suburban; I’m of the suburbs. I’ve spent my entire adulthood in cities, but I still get nostalgic when I smell freshly cut grass. It brings me back to the malls of my youth, to the food court at Town Center at Boca Raton, the mall we used to go to whenever I visited my grandparents in South Florida, or the old tobacco store in some forgotten shopping center in the middle of the country. I love grilling meat on a Weber grill I spent an hour trying to light, and by God, I miss not having a never-ending stream of cars honking outside my window.

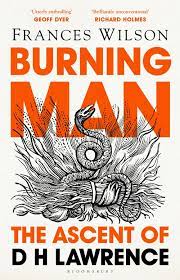

I’m suburban; I’m of the suburbs. I’ve spent my entire adulthood in cities, but I still get nostalgic when I smell freshly cut grass. It brings me back to the malls of my youth, to the food court at Town Center at Boca Raton, the mall we used to go to whenever I visited my grandparents in South Florida, or the old tobacco store in some forgotten shopping center in the middle of the country. I love grilling meat on a Weber grill I spent an hour trying to light, and by God, I miss not having a never-ending stream of cars honking outside my window. Burning Man, a new biography of Lawrence stuffed with fascinating research – his battleground of a childhood, his “raid” on literary London, life in Cornwall with Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry, lifelong denials of, and battles with, tuberculosis, referred to by him as “the bronchials”, his first meeting with Frieda von Richthofen, his “destiny” and life partner, fights between them, their penniless travels on foot, donkey and ferry throughout Europe, in Florence with Norman Douglas, the pilgrimage to New Mexico and Mabel Dodge, her quest to “save” the Pueblo Indians, his novels, poems and literary criticisms ‑ is wonderful in many ways; but here’s my caveat: can a new biography of Lawrence really ignore Kate Millet’s critique of his work, declaring him one of the subtlest propagators of sexist, patriarchal propaganda? Can his novels, seen by Millet as laying the groundwork for today’s pornography, really stand unquestioned?

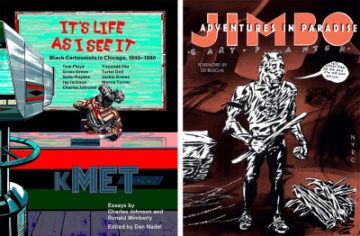

Burning Man, a new biography of Lawrence stuffed with fascinating research – his battleground of a childhood, his “raid” on literary London, life in Cornwall with Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murry, lifelong denials of, and battles with, tuberculosis, referred to by him as “the bronchials”, his first meeting with Frieda von Richthofen, his “destiny” and life partner, fights between them, their penniless travels on foot, donkey and ferry throughout Europe, in Florence with Norman Douglas, the pilgrimage to New Mexico and Mabel Dodge, her quest to “save” the Pueblo Indians, his novels, poems and literary criticisms ‑ is wonderful in many ways; but here’s my caveat: can a new biography of Lawrence really ignore Kate Millet’s critique of his work, declaring him one of the subtlest propagators of sexist, patriarchal propaganda? Can his novels, seen by Millet as laying the groundwork for today’s pornography, really stand unquestioned? It’s terrifying how optimistic that era’s pessimism now seems. In Adventures in Paradise’s view of the future, we’re all fucked, to be sure, but at least we get to go to Mars, hang out with sentient robots, expand, accelerate, etc. The last four decades seems to have brought something like a great lowering of expectations, which David Graeber described like so: “A timid, bureaucratic spirit suffuses every aspect of cultural life. It comes festooned in a language of creativity, initiative, and entrepreneurialism. But the language is meaningless. . . . The greatest and most powerful nation that has ever existed has spent the last decades telling its citizens they can no longer contemplate fantastic collective enterprises.” Graeber singled out scientists and politicians for their contracting imaginations, but the creative class isn’t exempt— just look at the extraordinary success of Marvel Studios, the company whose fizzling pyrotechnics and brand-management-disguised-as-entertainment are a shadow of the American comic-book tradition to which Gary Panter has added so much.

It’s terrifying how optimistic that era’s pessimism now seems. In Adventures in Paradise’s view of the future, we’re all fucked, to be sure, but at least we get to go to Mars, hang out with sentient robots, expand, accelerate, etc. The last four decades seems to have brought something like a great lowering of expectations, which David Graeber described like so: “A timid, bureaucratic spirit suffuses every aspect of cultural life. It comes festooned in a language of creativity, initiative, and entrepreneurialism. But the language is meaningless. . . . The greatest and most powerful nation that has ever existed has spent the last decades telling its citizens they can no longer contemplate fantastic collective enterprises.” Graeber singled out scientists and politicians for their contracting imaginations, but the creative class isn’t exempt— just look at the extraordinary success of Marvel Studios, the company whose fizzling pyrotechnics and brand-management-disguised-as-entertainment are a shadow of the American comic-book tradition to which Gary Panter has added so much. It is no coincidence that caffeine and the minute-hand on clocks arrived at around the same historical moment, the acclaimed food and nature writer Michael Pollan argues in his latest book, This is Your Mind on Plants. Both spread across Europe as labourers began leaving the fields, where work is organised around the sun, for the factories, where shift-workers could no longer adhere to their natural patterns of sleep and wakefulness. Would capitalism even have been possible without caffeine?

It is no coincidence that caffeine and the minute-hand on clocks arrived at around the same historical moment, the acclaimed food and nature writer Michael Pollan argues in his latest book, This is Your Mind on Plants. Both spread across Europe as labourers began leaving the fields, where work is organised around the sun, for the factories, where shift-workers could no longer adhere to their natural patterns of sleep and wakefulness. Would capitalism even have been possible without caffeine? Biologist Teruhiko Wakayama envisions that one day, humans could populate other planets and seed new civilizations with animal sperm and egg cells they bring from Earth. Expanding humanity’s footprint into deep space will necessitate that humans ship out “Noah’s Arks” of this genetic material, each batch of cells a delegate of Earth’s biodiversity.

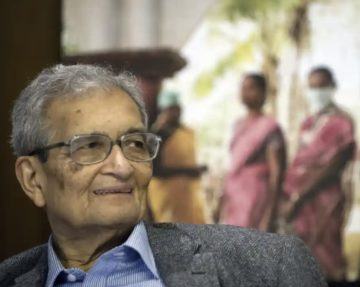

Biologist Teruhiko Wakayama envisions that one day, humans could populate other planets and seed new civilizations with animal sperm and egg cells they bring from Earth. Expanding humanity’s footprint into deep space will necessitate that humans ship out “Noah’s Arks” of this genetic material, each batch of cells a delegate of Earth’s biodiversity. Amartya Sen was 18 when he diagnosed his own cancer. Not long after he had moved to Calcutta for college, he noticed a lump growing inside his mouth. He consulted two doctors but they laughed away his suspicions, so Sen, then a student of economics and mathematics, looked up a couple of books on cancer from a medical library. He identified the tumour – a “squamous cell carcinoma” – and later when a biopsy confirmed his verdict he wondered if there were in effect two people with his name: a patient who had just been told he had cancer, but also the “agent” responsible for the diagnosis. “I must not let the agent in me go away,” Sen decided, “and could not – absolutely could not – let the patient take over completely.”

Amartya Sen was 18 when he diagnosed his own cancer. Not long after he had moved to Calcutta for college, he noticed a lump growing inside his mouth. He consulted two doctors but they laughed away his suspicions, so Sen, then a student of economics and mathematics, looked up a couple of books on cancer from a medical library. He identified the tumour – a “squamous cell carcinoma” – and later when a biopsy confirmed his verdict he wondered if there were in effect two people with his name: a patient who had just been told he had cancer, but also the “agent” responsible for the diagnosis. “I must not let the agent in me go away,” Sen decided, “and could not – absolutely could not – let the patient take over completely.” Fifteen months after the novel coronavirus shut down much of the world, the pandemic is still raging. Few experts guessed that by this point, the world would have not one vaccine but many, with 3 billion doses already delivered. At the same time, the coronavirus has evolved into super-transmissible variants that spread more easily. The clash between these variables will define the coming months and seasons. Here, then, are three simple principles to understand how they interact. Each has caveats and nuances, but together, they can serve as a guide to our near-term future.

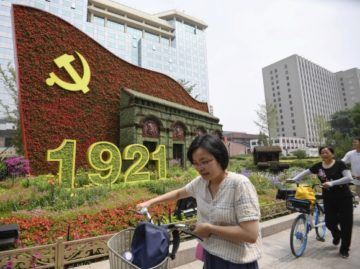

Fifteen months after the novel coronavirus shut down much of the world, the pandemic is still raging. Few experts guessed that by this point, the world would have not one vaccine but many, with 3 billion doses already delivered. At the same time, the coronavirus has evolved into super-transmissible variants that spread more easily. The clash between these variables will define the coming months and seasons. Here, then, are three simple principles to understand how they interact. Each has caveats and nuances, but together, they can serve as a guide to our near-term future. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will trumpet its own version of history as it celebrates its centenary on Thursday, and remind its citizens and the world of its centrality to China’s lofty economic and global aspirations in the decades ahead. It rules with a swagger about its accomplishments and a grand narrative about the future, and yet also with a repression and prickliness that are more consistent with a state of siege. China’s party leaders still fret about what happened to their Soviet counterparts and are determined to avoid a similar fate. China’s Leninist party has fared much better, but it nevertheless has good reason to be wary that the 2020s will be an important acid test.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will trumpet its own version of history as it celebrates its centenary on Thursday, and remind its citizens and the world of its centrality to China’s lofty economic and global aspirations in the decades ahead. It rules with a swagger about its accomplishments and a grand narrative about the future, and yet also with a repression and prickliness that are more consistent with a state of siege. China’s party leaders still fret about what happened to their Soviet counterparts and are determined to avoid a similar fate. China’s Leninist party has fared much better, but it nevertheless has good reason to be wary that the 2020s will be an important acid test.

For 27 July 1794, ‘9 Thermidor Year II’ in the new republican calendar, has long been recognised as a ‘pivotal moment’ in the French Revolution. Until that point, the course of the revolution had been marked by increasing radicalism: France had gone from constitutional monarchy after the fall of the Bastille in 1789, to kingless republic in 1792, to wartime police state from 1793. After the events of 9 Thermidor, the trend was towards increasing conservatism. The democratic and reformist energies of the early revolution were mostly dissipated. Within a decade, France was again a monarchy, with a Corsican-born emperor in place of a Bourbon king.

For 27 July 1794, ‘9 Thermidor Year II’ in the new republican calendar, has long been recognised as a ‘pivotal moment’ in the French Revolution. Until that point, the course of the revolution had been marked by increasing radicalism: France had gone from constitutional monarchy after the fall of the Bastille in 1789, to kingless republic in 1792, to wartime police state from 1793. After the events of 9 Thermidor, the trend was towards increasing conservatism. The democratic and reformist energies of the early revolution were mostly dissipated. Within a decade, France was again a monarchy, with a Corsican-born emperor in place of a Bourbon king. I spent many years thinking about how to design an imaging study that could identify the unique features of the creative brain. Most of the human brain’s functions arise from the 6 layers of nerve cells and their dendrites embedded in its enormous surface area, called the cerebral cortex — which is compressed to a size small enough to be carried around on our shoulders through a process known as gyrification — essentially, producing lots of folds.

I spent many years thinking about how to design an imaging study that could identify the unique features of the creative brain. Most of the human brain’s functions arise from the 6 layers of nerve cells and their dendrites embedded in its enormous surface area, called the cerebral cortex — which is compressed to a size small enough to be carried around on our shoulders through a process known as gyrification — essentially, producing lots of folds. IMPLEMENTATION of the PTI’s Single National Curriculum has started in Islamabad’s schools and for students the human body is to become a dark mystery, darker than ever before. Religious scholars appointed as members of the SNC Committee are

IMPLEMENTATION of the PTI’s Single National Curriculum has started in Islamabad’s schools and for students the human body is to become a dark mystery, darker than ever before. Religious scholars appointed as members of the SNC Committee are