John Bowen in Boston Review:

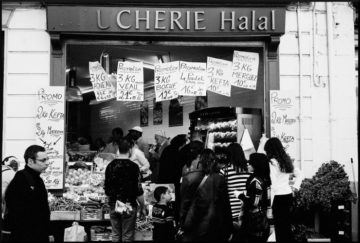

Last October, while waging the government’s new campaign against Islamic forms of “separatism,” French Interior minister Gérald Darmanin complained on television that he was frequently “shocked” to enter a supermarket and see a shelf of “communalist food” (cuisine communautaire).

Last October, while waging the government’s new campaign against Islamic forms of “separatism,” French Interior minister Gérald Darmanin complained on television that he was frequently “shocked” to enter a supermarket and see a shelf of “communalist food” (cuisine communautaire).

Darmanin later expanded on his remarks, clarifying that he does not deny that people have a right to eat halal and kosher products (the “communalist foods” in question). He does, however, regret that capitalist profit-seekers advertised foods intended only for one segment of society in such a public way, and, even worse, in food shops patronized by all sorts of people. This, he contended, weakened the Republic by encouraging “separatism.” Of course, despite the intentional vagueness of the term “communalist,” few would have thought that the Minister had kosher pizzas in mind. Rather, he was signaling his annoyance at the myriad ways that—after hijabs in schools and on Decathalon jogging outfits—Muslims were again publicly holding back on their commitment to the Republic.

Darmanin’s remarks are but one version of a growing, broadly European complaint that halal food divides citizens, violates norms of animal welfare, and stealthily intrudes Islam into Western society. This complaint, and the measures that have begun to follow, shift depending on the post-colonial and anti-Islamic politics in each country. On this issue, politics is at once local, regional, and global. But why has access to religiously appropriate food assumed such political importance across Europe?

More here.

To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves, whether with telescopes and microscopes and our ever-burgeoning technology, or in states of mind that allow us to travel to other worlds, to rise above our immediate surroundings. We may seek, too, a relaxing of inhibitions that makes it easier to bond with each other, or transports that make our consciousness of time and mortality easier to bear. We seek a holiday from our inner and outer restrictions, a more intense sense of the here and now, the beauty and value of the world we live in.

To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves, whether with telescopes and microscopes and our ever-burgeoning technology, or in states of mind that allow us to travel to other worlds, to rise above our immediate surroundings. We may seek, too, a relaxing of inhibitions that makes it easier to bond with each other, or transports that make our consciousness of time and mortality easier to bear. We seek a holiday from our inner and outer restrictions, a more intense sense of the here and now, the beauty and value of the world we live in. Tove Jansson’s writing is different. She has wonderful passages in which entire landscapes are made by peering at blades of grass and scraps of bark. Yet her main Moomin adventures are startlingly catastrophic. For all the light clarity of the prose – which is comic, benign and quizzical – these books show places gripped by ferocious forces, laid waste by storms and floods and snows. They speak (but never obviously) of characters resonating to the winds and seas around them. They include visions that now read like warnings of climate change: “the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat”.

Tove Jansson’s writing is different. She has wonderful passages in which entire landscapes are made by peering at blades of grass and scraps of bark. Yet her main Moomin adventures are startlingly catastrophic. For all the light clarity of the prose – which is comic, benign and quizzical – these books show places gripped by ferocious forces, laid waste by storms and floods and snows. They speak (but never obviously) of characters resonating to the winds and seas around them. They include visions that now read like warnings of climate change: “the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat”. Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, “Inside U.S.A.” — more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies — the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers — plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman’s “Peace of Mind” and the “Information Please Almanac”). It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther’s first great success, “Inside Europe,” published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; “Inside Asia” and “Inside Latin America” followed, with comparable success — all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be “Inside Africa” and “Inside Russia Today,” yet to come. His “Roosevelt in Retrospect” (1950) is one of the best political biographies I’ve ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like “Inside U.S.A.,” it is out of print — please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear.

Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, “Inside U.S.A.” — more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies — the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers — plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman’s “Peace of Mind” and the “Information Please Almanac”). It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther’s first great success, “Inside Europe,” published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; “Inside Asia” and “Inside Latin America” followed, with comparable success — all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be “Inside Africa” and “Inside Russia Today,” yet to come. His “Roosevelt in Retrospect” (1950) is one of the best political biographies I’ve ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like “Inside U.S.A.,” it is out of print — please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear. Wolfgang Streeck in the New Left Review‘s Sidecar:

Wolfgang Streeck in the New Left Review‘s Sidecar: Matthieu Queloz in Aeon:

Matthieu Queloz in Aeon: Robert Pollin and Gerald Epstein in Boston Review:

Robert Pollin and Gerald Epstein in Boston Review: Paul J. D’Ambrosio in the LA Review of Books:

Paul J. D’Ambrosio in the LA Review of Books: A

A When reptile breeder Steve Sykes saw that two particular

When reptile breeder Steve Sykes saw that two particular  I have said fuck off to the most powerful man in the world. Maybe you did too. It was on Twitter, which gave me some distance, but I stand by my word choice. It was the right thing to do.

I have said fuck off to the most powerful man in the world. Maybe you did too. It was on Twitter, which gave me some distance, but I stand by my word choice. It was the right thing to do. Practically everywhere we look in the Universe, the large-scale objects that we see — small galaxies, large galaxies, groups and clusters of galaxies, and even the great cosmic web — all not only contain dark matter, but require it. Only in a Universe with far more mass than normal matter can provide, and in a different form from the protons, neutrons, and electrons that scatter and interact with themselves and with light, can our observations be explained. However, an interesting consequence should arise in a Universe with dark matter: the existence of a small but significant population of galaxies containing no dark matter at all.

Practically everywhere we look in the Universe, the large-scale objects that we see — small galaxies, large galaxies, groups and clusters of galaxies, and even the great cosmic web — all not only contain dark matter, but require it. Only in a Universe with far more mass than normal matter can provide, and in a different form from the protons, neutrons, and electrons that scatter and interact with themselves and with light, can our observations be explained. However, an interesting consequence should arise in a Universe with dark matter: the existence of a small but significant population of galaxies containing no dark matter at all. Directly following the 2020 election, Republicans seemed to be through with Donald Trump.

Directly following the 2020 election, Republicans seemed to be through with Donald Trump.