Juan Siliezar in The Harvard Gazette:

Contemporary Americans have access to custom workout routines, fancy gyms, and high-end home equipment like Peloton machines. Even so, when it comes to physical activity, our forebears of two centuries ago beat us by about 30 minutes a day, according to a new Harvard study.

Contemporary Americans have access to custom workout routines, fancy gyms, and high-end home equipment like Peloton machines. Even so, when it comes to physical activity, our forebears of two centuries ago beat us by about 30 minutes a day, according to a new Harvard study.

Researchers from the lab of evolutionary biologist Daniel E. Lieberman used data on falling body temperatures and changing metabolic rates to compare current levels of physical activity in the United States with those of the early 19th century. The work is described in Current Biology. The scientists found that Americans’ resting metabolic rate — the total number of calories burned when the body is completely at rest — has fallen by about 6 percent since 1820, which translates to 27 fewer minutes of daily exercise. The culprit, the authors say, is technology.

“Instead of walking to work, we take cars or trains; instead of manual labor in factories, we use machines,” said Andrew K. Yegian, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Human and Evolutionary Biology and the paper’s lead author. “We’ve made technology to do our physical activity for us. … Our hope is that this helps people think more about the long-term changes of activity that have come with our changes in lifestyle and technology.”

While it’s been well documented that technological and social changes have reduced levels of physical activity the past two centuries, the precise drop-off had never been calculated. The paper puts a quantitative number to the literature and shows that historical records of resting body temperature may be able to serve as a measure of population-level physical activity.

More here.

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times. There is a world, not too dissimilar from our own, in which Jonathan Franzen is a professor of creative writing at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. He still has his bylines at the New Yorker and Harper’s (in fact, he writes for them more frequently); he still has his books (even if they’re all a bit shorter, one of them is a collection of short stories, and his translation of Spring Awakening lives with his unpublished notes on Karl Kraus in the Amish-made drawer of his ‘archive’); he still has his awards (except his NBA is now an NEA). Despite his misgivings about the effect of social media on print culture, he also has a Facebook page, which he uses to promote his readings and share photos of his outings with the local birding society, and a Twitter account, which he uses to retweet positive reviews and post about Julian Assange. Aside from his anxiety about how much time teaching and administrative duties take away from his ‘real work’ as a novelist, whether his diminishing royalty checks will be enough to cover his mortgage and his adopted son’s college tuition, and whether it would be wise to keep flirting with the sole female member of his small group of student acolytes, the greatest drama in his life occurs when he periodically becomes the main character on Twitter for saying something hopelessly out of touch – pile-ons he less-than-discreetly attributes to other writers’ envy for his hard-won success.

There is a world, not too dissimilar from our own, in which Jonathan Franzen is a professor of creative writing at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. He still has his bylines at the New Yorker and Harper’s (in fact, he writes for them more frequently); he still has his books (even if they’re all a bit shorter, one of them is a collection of short stories, and his translation of Spring Awakening lives with his unpublished notes on Karl Kraus in the Amish-made drawer of his ‘archive’); he still has his awards (except his NBA is now an NEA). Despite his misgivings about the effect of social media on print culture, he also has a Facebook page, which he uses to promote his readings and share photos of his outings with the local birding society, and a Twitter account, which he uses to retweet positive reviews and post about Julian Assange. Aside from his anxiety about how much time teaching and administrative duties take away from his ‘real work’ as a novelist, whether his diminishing royalty checks will be enough to cover his mortgage and his adopted son’s college tuition, and whether it would be wise to keep flirting with the sole female member of his small group of student acolytes, the greatest drama in his life occurs when he periodically becomes the main character on Twitter for saying something hopelessly out of touch – pile-ons he less-than-discreetly attributes to other writers’ envy for his hard-won success. Although I’ve successfully learned the language of mathematics, it has always frustrated me that I couldn’t master those more unpredictable languages like French or Russian that I’d tried to learn in hopes of becoming a spy. Although Gauss too left his love of languages behind to pursue a career in mathematics, he did actually return to the challenge of learning new languages in later life, such as Sanskrit and Russian. At the age of 64, after two years of study, he had mastered Russian well enough to read Pushkin in the original. Inspired by Gauss’s example, I’ve decided to revisit my attempts at learning Russian.

Although I’ve successfully learned the language of mathematics, it has always frustrated me that I couldn’t master those more unpredictable languages like French or Russian that I’d tried to learn in hopes of becoming a spy. Although Gauss too left his love of languages behind to pursue a career in mathematics, he did actually return to the challenge of learning new languages in later life, such as Sanskrit and Russian. At the age of 64, after two years of study, he had mastered Russian well enough to read Pushkin in the original. Inspired by Gauss’s example, I’ve decided to revisit my attempts at learning Russian. If there is a utopian kernel to be found in this pandemic, so replete with dystopian terror, it is most certainly that each day more and more people have grown to hate the world of work. Some of us, certainly a lucky few, might even enjoy our jobs, or certain aspects of them, but all the same, work under capitalism has become increasingly legible as a system of false promises—deferred freedom, self-actualization, leisure, joy, safety, or whatever else we might value that cannot be reduced to the accumulation of capital.

If there is a utopian kernel to be found in this pandemic, so replete with dystopian terror, it is most certainly that each day more and more people have grown to hate the world of work. Some of us, certainly a lucky few, might even enjoy our jobs, or certain aspects of them, but all the same, work under capitalism has become increasingly legible as a system of false promises—deferred freedom, self-actualization, leisure, joy, safety, or whatever else we might value that cannot be reduced to the accumulation of capital. Colm Tóibín presents us with one account of Mann’s gradual progress away from German nationalism. It might not be the last word on what seems to have been a complex and tortured journey, but it functions well in the context of the demands of a novel, where the shifts in perspective must be presented dramatically and are often portrayed through Thomas’s interactions with others, principally members of his large and turbulent family. First and most important of these is his wife, Katia Pringsheim, who is deeply suspicious of his friendship with the nationalist (and later Nazi) writer Ernst Bertram. On the outbreak of the First World War Katia asks her husband to consider how they would feel if their two boys, Klaus and Golo, were old enough to be conscripted, “and we were waiting here each day for news of them”: “And all because of some idea.”

Colm Tóibín presents us with one account of Mann’s gradual progress away from German nationalism. It might not be the last word on what seems to have been a complex and tortured journey, but it functions well in the context of the demands of a novel, where the shifts in perspective must be presented dramatically and are often portrayed through Thomas’s interactions with others, principally members of his large and turbulent family. First and most important of these is his wife, Katia Pringsheim, who is deeply suspicious of his friendship with the nationalist (and later Nazi) writer Ernst Bertram. On the outbreak of the First World War Katia asks her husband to consider how they would feel if their two boys, Klaus and Golo, were old enough to be conscripted, “and we were waiting here each day for news of them”: “And all because of some idea.” I

I What if

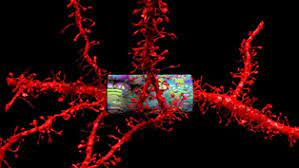

What if  On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement.

On a chilly evening last fall, I stared into nothingness out of the floor-to-ceiling windows in my office on the outskirts of Harvard’s campus. As a purplish-red sun set, I sat brooding over my dataset on rat brains. I thought of the cold windowless rooms in downtown Boston, home to Harvard’s high-performance computing center, where computer servers were holding on to a precious 48 terabytes of my data. I have recorded the 13 trillion numbers in this dataset as part of my Ph.D. experiments, asking how the visual parts of the rat brain respond to movement. The story of rising economic inequality is by now so familiar that it fits easily onto a T-shirt. But the way the story is told is often imprecise enough to leave out much of the plot. “We are the 99 percent” sounds righteous enough, but it’s a slogan, not an analysis. It suggests that the whole issue is about “them,” a tiny group of crazy rich people, who are nothing at all like “us.” But that’s not how inequality has ever worked. You can glimpse the outlines of the problem if you take a closer look at the math of inequality.

The story of rising economic inequality is by now so familiar that it fits easily onto a T-shirt. But the way the story is told is often imprecise enough to leave out much of the plot. “We are the 99 percent” sounds righteous enough, but it’s a slogan, not an analysis. It suggests that the whole issue is about “them,” a tiny group of crazy rich people, who are nothing at all like “us.” But that’s not how inequality has ever worked. You can glimpse the outlines of the problem if you take a closer look at the math of inequality. The problems originate in the mundane practices of computer coding. Machine learning reveals patterns in data — such algorithms learn, for example, how to identify common features of “cupness” from processing many, many pictures of cups. The approach is increasingly used by businesses and government agencies; in addition to facial recognition systems, it’s behind Facebook’s news feed and targeting of advertisements, digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa, guidance systems for autonomous vehicles, some

The problems originate in the mundane practices of computer coding. Machine learning reveals patterns in data — such algorithms learn, for example, how to identify common features of “cupness” from processing many, many pictures of cups. The approach is increasingly used by businesses and government agencies; in addition to facial recognition systems, it’s behind Facebook’s news feed and targeting of advertisements, digital assistants such as Siri and Alexa, guidance systems for autonomous vehicles, some  Squid Game is not a subtle show, either in its politics or plot. Capitalism is bloody and mean and relentless; it yells. Each episode moves from one game to the next, in a series that, by the end, combined with some awkward English-language dialogue, feels hopelessly strained. But the show redeems itself with its memorable characters (all archetypal strugglers) and its bright, video-game-inspired design. The art director, Choi Kyoung-sun, said that she wanted to build a “storybook” world—a child’s late-capitalist hell—and she has done so brilliantly.

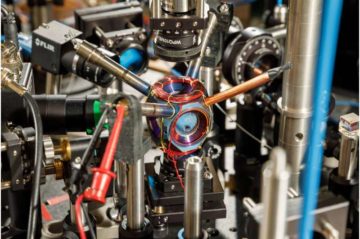

Squid Game is not a subtle show, either in its politics or plot. Capitalism is bloody and mean and relentless; it yells. Each episode moves from one game to the next, in a series that, by the end, combined with some awkward English-language dialogue, feels hopelessly strained. But the show redeems itself with its memorable characters (all archetypal strugglers) and its bright, video-game-inspired design. The art director, Choi Kyoung-sun, said that she wanted to build a “storybook” world—a child’s late-capitalist hell—and she has done so brilliantly. Countless devices around the world use GPS for wayfinding. It’s possible because atomic clocks, which are known for extremely accurate timekeeping, hold the network of satellites perfectly in sync.

Countless devices around the world use GPS for wayfinding. It’s possible because atomic clocks, which are known for extremely accurate timekeeping, hold the network of satellites perfectly in sync. Liz Harris always seems to be telling us a secret. The catch—and the thing that makes her music as

Liz Harris always seems to be telling us a secret. The catch—and the thing that makes her music as