Nick Paumgarten in The New Yorker:

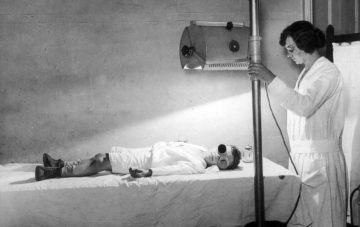

For months, during the main pandemic stretch, I’d get inexplicably tired in the afternoon, as though vital organs and muscles had turned to Styrofoam. Just sitting in front of a computer screen, in sweatpants and socks, left me drained. It seemed ridiculous to be grumbling about fatigue when so many people were suffering through so much more. But we feel how we feel. Nuke a cup of cold coffee, take a walk around the block: the standard tactics usually did the trick. But one advantage, or disadvantage, of working from home is the proximity of a bed. Now and then, you surrender. These midafternoon doldrums weren’t entirely unfamiliar. Even back in the office years, with editors on the prowl, I learned to sneak the occasional catnap under my desk, alert as a zebra to the telltale footfall of a consequential approach. At home, though, you could power all the way down.

For months, during the main pandemic stretch, I’d get inexplicably tired in the afternoon, as though vital organs and muscles had turned to Styrofoam. Just sitting in front of a computer screen, in sweatpants and socks, left me drained. It seemed ridiculous to be grumbling about fatigue when so many people were suffering through so much more. But we feel how we feel. Nuke a cup of cold coffee, take a walk around the block: the standard tactics usually did the trick. But one advantage, or disadvantage, of working from home is the proximity of a bed. Now and then, you surrender. These midafternoon doldrums weren’t entirely unfamiliar. Even back in the office years, with editors on the prowl, I learned to sneak the occasional catnap under my desk, alert as a zebra to the telltale footfall of a consequential approach. At home, though, you could power all the way down.

Still, the ebb, lately, had become acute, and hard to account for. By the standards of my younger years, I was burning the candle at neither end. Could one attribute it to the wine the night before, the cookies, the fitful and abbreviated sleep, the boomerang effect of the morning’s caffeine and carbs, a sedentary profession, middle age? That will be a yes. And yet the mind roamed: covid? Lyme? Diabetes? Cancer? It’s no hipaa violation to reveal that, as various checkups determined, none of those pertained. So, embrace it. A recent headline in the Guardian: “Extravagant eye bags: How extreme exhaustion became this year’s hottest look.”

It was just a question of energy. The endurance athlete, running perilously low on fuel, is said to hit the wall, or bonk. Cyclists call this feeling “the man with the hammer.” Applying the parlance to the Sitzfleisch life, I told myself that I was bonking. At hour five in the desk chair, the document onscreen looked like a winding road toward a mountain pass. The man in the sweatpants had met the man with the mattress.

More here.

But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments.

But Berlin is also a city receptive to wanderers conversing with death, loners who find themselves at the end of the road. For the Polish reader, there is no more important description of Berlin, of its mood, people, and places—all of them passed by with equal haste—than the fragments, from 1963, of Witold Gombrowicz’s diary. These pages offer a valuable introduction to the city; reading them carefully sends shivers down the spine. It is necessary to treat them as a standard of free writing and of a literature always on the side of life, though also one that is drawn towards life’s final moments.

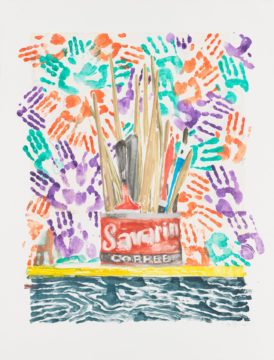

His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.”

His styles are legion—well organized in this show by the curators Scott Rothkopf, in New York, and Carlos Basualdo, in Philadelphia, with contrasts and echoes that forestall a possibility of feeling overwhelmed. Each place tells a complete story. Regarding early work, New York gets most of the Flags and Philadelphia most of the Numbers. Again, looking rules, as in the case of my favorite paintings of Johns’s mid-career phase, spectacular variations on color-field abstraction that present allover clusters of diagonal marks—that is, hatchings. These are often misleadingly termed “crosshatch,” even by Johns himself, but the marks never cross. Each bundle has a zone of the picture plane to itself, to keep his designs stretched flat, while they are supercharged by plays of touch and color and sometimes poeticized with piquant titles: “Corpse and Mirror,” for example, or “Scent.” For months, during the main

For months, during the main  It’s been more than 50 years since

It’s been more than 50 years since  The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.”

The idea of epiphany summons two thoughts, generally. One is religious: the sudden and overwhelming appearance of the Divine into everyday life, as experienced, for instance, by Julian of Norwich, Teresa of Avila, and many holy figures through the ages. The other is literary. Epiphany is now perhaps as strongly, or even more strongly, connected to a certain idea expressed in European modernism, and emphasized in its aftermath. The idea is especially prominent in Joyce’s two early prose works, Dubliners—which includes “The Dead”—and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Epiphany, as understood by Joyce, and practiced thereafter, has to do with heightened sensation and flashes of insight, often of the kind that helps a character solve a problem. This is the definition he gave the term, in an early version of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “a sudden spiritual manifestation.” As the coronavirus pandemic recedes in the advanced economies, their central banks increasingly resemble the proverbial ass who, equally hungry and thirsty, succumbs to both hunger and thirst because it could not choose between hay and water. Torn between inflationary jitters and fear of deflation, policymakers are taking a potentially costly wait-and-see approach. Only a progressive rethink of their tools and aims can help them play a socially useful post-pandemic role.

As the coronavirus pandemic recedes in the advanced economies, their central banks increasingly resemble the proverbial ass who, equally hungry and thirsty, succumbs to both hunger and thirst because it could not choose between hay and water. Torn between inflationary jitters and fear of deflation, policymakers are taking a potentially costly wait-and-see approach. Only a progressive rethink of their tools and aims can help them play a socially useful post-pandemic role. Edward Said loved music, and I loved his love of music as well as the musicality that characterized everything he did. Because of his writings on late style, I think of him in connection with Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 15, op. 132. This was Beethoven’s thirteenth quartet, but the fifteenth in order of publication. It’s the kind of work that tempts one to agree with the strange notion that there is such a thing as pure music, music better than any possible performance. This is a romantic idea, and it’s probably not true, since music exists in the hearing, not on the page. But listening to Beethoven’s Op. 132, you can see why people think so. Within the written tradition of Western classical music, as in all genres of music, there is music that exhausts superlatives. Late Beethoven emerges coherently out of mature Beethoven, and mature Beethoven is an extension and fulfillment of early Beethoven. These are major shifts and distinct modes of evolution, but they are not radical breaks.

Edward Said loved music, and I loved his love of music as well as the musicality that characterized everything he did. Because of his writings on late style, I think of him in connection with Beethoven’s String Quartet no. 15, op. 132. This was Beethoven’s thirteenth quartet, but the fifteenth in order of publication. It’s the kind of work that tempts one to agree with the strange notion that there is such a thing as pure music, music better than any possible performance. This is a romantic idea, and it’s probably not true, since music exists in the hearing, not on the page. But listening to Beethoven’s Op. 132, you can see why people think so. Within the written tradition of Western classical music, as in all genres of music, there is music that exhausts superlatives. Late Beethoven emerges coherently out of mature Beethoven, and mature Beethoven is an extension and fulfillment of early Beethoven. These are major shifts and distinct modes of evolution, but they are not radical breaks. Any account of childhood written by an adult might quickly become a work of adult art, presenting the child’s world, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility foreign to the experiences of being young. With his intensely concentrated gaze and voluptuous yet exact prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a work of vivid immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats’s poetry: Brought this close up to what it feels like to be a child, or for that matter an adult, Wollheim helps us see with awful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be alive.

Any account of childhood written by an adult might quickly become a work of adult art, presenting the child’s world, its highlights and its shadows, with a sensibility foreign to the experiences of being young. With his intensely concentrated gaze and voluptuous yet exact prose style, however, Wollheim offers us a work of vivid immediacy. Reading it, one experiences the kind of embarrassment that the critic Christopher Ricks identified in Keats’s poetry: Brought this close up to what it feels like to be a child, or for that matter an adult, Wollheim helps us see with awful clarity what an emotional and moral predicament it is to be alive. Electric vehicles have the potential

Electric vehicles have the potential

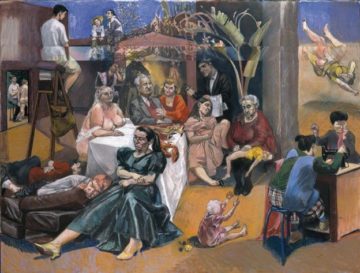

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream.

There’s a painting entitled Celestina’s House (2000-1). I count at least twenty-two figures in the painting. That’s a rough count. A few of these figures are sitting around a table, presumably eating a meal, though the only food on the table is a lobster and crab, maybe still alive. In front of the table, several figures nap awkwardly on pillows while, nearby, a tiny old woman sits on the floor, reaching up like a baby. Elsewhere, two women work, disconsolate, at a sewing machine, another woman falls down backward through the air, and a young fellow sits on a ladder with his back to us, as if he’s being punished. There is so much going on it is impossible to understand exactly what is going on. It is a scene, perhaps, showing us what would happen if the entire contents of many nights’ dreaming were smashed onto one canvas. The style is more or less realist, but not fastidiously so. We seem to be firmly in the realm of fantasy, memory, fable, and dream. Dear Prime Minister Boris Johnson, I want to thank you and COP President Alok Sharma for your hospitality, leadership, and tireless efforts in the preparation of this COP.

Dear Prime Minister Boris Johnson, I want to thank you and COP President Alok Sharma for your hospitality, leadership, and tireless efforts in the preparation of this COP. Brood with me on the latest delay of the full release of the records pertaining to the murder of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. That was 58 years ago. More time has passed since October 26, 1992, when Congress mandated the full and immediate release of almost all the JFK assassination records, than had elapsed between the killing and the passage of that law.

Brood with me on the latest delay of the full release of the records pertaining to the murder of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. That was 58 years ago. More time has passed since October 26, 1992, when Congress mandated the full and immediate release of almost all the JFK assassination records, than had elapsed between the killing and the passage of that law. J

J