The Latin Deli: An Ars Poetica

Presiding over a formica counter,

plastic Mother and Child magnetized

to the top of an ancient register,

the heady mix of smells from the open bins

of dried codfish, the green plantains

hanging in stalks like votive offerings,

she is the Patroness of Exiles,

a woman of no-age who was never pretty,

who spends her days selling canned memories

while listening to the Puerto Ricans complain

that it would be cheaper to fly to San Juan

than to buy a pound of Bustelo coffee here,

and to Cubans perfecting their speech

of a “glorious return” to Havana–where no one

has been allowed to die and nothing to change until then;

to Mexicans who pass through, talking lyrically

of dólares to be made in El Norte–

all wanting the comfort

of spoken Spanish, to gaze upon the family portrait

of her plain wide face, her ample bosom

resting on her plump arms, her look of maternal interest

as they speak to her and each other

of their dreams and their disillusions–

how she smiles understanding,

when they walk down the narrow aisles of her store

reading the labels of packages aloud, as if

they were the names of lost lovers; Suspiros,

Merengues, the stale candy of everyone’s childhood.

She spends her days

slicing jamón y queso and wrapping it in wax paper

tied with string: plain ham and cheese

that would cost less at the A&P, but it would not satisfy

the hunger of the fragile old man lost in the folds

of his winter coat, who brings her lists of items

that he reads to her like poetry, or the other,

whose needs she must divine, conjuring up products

from places that now exist only in their hearts–

closed ports she must trade with.

by Judith Ortiz Cofer

from Literary Paterson

In May 1453, Ottoman military forces under Sultan Mehmed II captured the once great Byzantine capital of Constantinople, now Istanbul. It was a landmark moment. What was viewed as one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and described by the sultan as “the second Rome”, had fallen to Muslim conquerors. The sultan even called himself “caesar”.

In May 1453, Ottoman military forces under Sultan Mehmed II captured the once great Byzantine capital of Constantinople, now Istanbul. It was a landmark moment. What was viewed as one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and described by the sultan as “the second Rome”, had fallen to Muslim conquerors. The sultan even called himself “caesar”. We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand.

We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand. In the last chapter of his first book, Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, Spencer Ackerman reminds his readers of Bernie Sanders’s June 2019 assertion: “There is a straight line from the decision to reorient U.S. national-security strategy around terrorism after 9/11 to placing migrant children in cages on our southern border.”

In the last chapter of his first book, Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, Spencer Ackerman reminds his readers of Bernie Sanders’s June 2019 assertion: “There is a straight line from the decision to reorient U.S. national-security strategy around terrorism after 9/11 to placing migrant children in cages on our southern border.” Academics use the category of magic, well, often magically, to dismiss the phenomenon they are studying, to banish the subject matter from living contact with their present reality. Ancient philosophy is over there, good and dead, and we enlightened modern philosophers and scholars are over here, living, present, pristine and modern, washed clean of ancient superstitions. But magic is rather sticky, hard to wash off from the hands or the delicate underside of the modern mind, to which it clings like a sinister visitor who has always arrived, but is still waiting to announce itself.

Academics use the category of magic, well, often magically, to dismiss the phenomenon they are studying, to banish the subject matter from living contact with their present reality. Ancient philosophy is over there, good and dead, and we enlightened modern philosophers and scholars are over here, living, present, pristine and modern, washed clean of ancient superstitions. But magic is rather sticky, hard to wash off from the hands or the delicate underside of the modern mind, to which it clings like a sinister visitor who has always arrived, but is still waiting to announce itself. Take the word “understand;” in daily communication we rarely parse it’s implications, but the word itself is a spatial metaphor. Linguist Guy Deutscher explains in

Take the word “understand;” in daily communication we rarely parse it’s implications, but the word itself is a spatial metaphor. Linguist Guy Deutscher explains in  For the longest part of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers who neither experienced economic growth nor worried about its absence. Instead of working many hours each day in order to acquire as much as possible, our nature—insofar as we have one—has been to do the minimum amount of work necessary to underwrite a good life.

For the longest part of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers who neither experienced economic growth nor worried about its absence. Instead of working many hours each day in order to acquire as much as possible, our nature—insofar as we have one—has been to do the minimum amount of work necessary to underwrite a good life. Sometimes our most precious cultural institutions fail to live up to their high educational and moral commitments and responsibilities. These failures especially damage the social fabric because they tend to harm many people who rely on them and tarnish the high ideals that the institutions claim to exemplify.

Sometimes our most precious cultural institutions fail to live up to their high educational and moral commitments and responsibilities. These failures especially damage the social fabric because they tend to harm many people who rely on them and tarnish the high ideals that the institutions claim to exemplify. We don’t know his real name. In early inscriptions it appears as Yhw, Yhwh, or simply Yh; but we don’t know how it was spoken. He has come to be known as Yahweh. Perhaps it doesn’t matter; by the third century BCE his name had been declared unutterable. We know him best as God.

We don’t know his real name. In early inscriptions it appears as Yhw, Yhwh, or simply Yh; but we don’t know how it was spoken. He has come to be known as Yahweh. Perhaps it doesn’t matter; by the third century BCE his name had been declared unutterable. We know him best as God. The body’s constellation of gut bacteria has been linked with various aging-associated illnesses, including cardiovascular disease and type 2

The body’s constellation of gut bacteria has been linked with various aging-associated illnesses, including cardiovascular disease and type 2  To this day nobody knows exactly what transpired in Selamon on that April night, in the year 1621, except that a lamp fell to the floor in the building where Martijn Sonck, a Dutch official, was billeted.

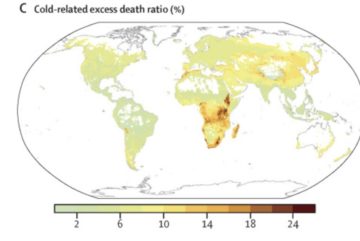

To this day nobody knows exactly what transpired in Selamon on that April night, in the year 1621, except that a lamp fell to the floor in the building where Martijn Sonck, a Dutch official, was billeted. People are most likely to die of extreme cold in Sub-Saharan Africa, and most likely to die of extreme heat in Greenland, Norway, and various very high mountains. You’re reading that right – the cold deaths are centered in the warmest areas, and vice versa.

People are most likely to die of extreme cold in Sub-Saharan Africa, and most likely to die of extreme heat in Greenland, Norway, and various very high mountains. You’re reading that right – the cold deaths are centered in the warmest areas, and vice versa. Francis Fukuyama: It’s a really old doctrine. And I think there are several reasons that it’s been around for such a long time: A pragmatic, political reason; a moral reason; and then there’s a very powerful economic one.

Francis Fukuyama: It’s a really old doctrine. And I think there are several reasons that it’s been around for such a long time: A pragmatic, political reason; a moral reason; and then there’s a very powerful economic one. The life and work of Stephen Crane derived gravity from brevity. Not one of his novels is much more than a hundred pages long, and they and his short stories strip language to its potent minimum. Crane’s short but prodigious life—he died, of tuberculosis, five months before his 29th birthday—observed the same concision. His hold on the public imagination has also lacked longevity. Crane’s most famous novel, The Red Badge of Courage (1895), is no longer required reading in American schools, and his other greatest hits—Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893), “The Open Boat” (1897), The Monster (1898), “The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky” (1898), and “The Blue Hotel” (1898)—have fallen out of the cultural conversation.

The life and work of Stephen Crane derived gravity from brevity. Not one of his novels is much more than a hundred pages long, and they and his short stories strip language to its potent minimum. Crane’s short but prodigious life—he died, of tuberculosis, five months before his 29th birthday—observed the same concision. His hold on the public imagination has also lacked longevity. Crane’s most famous novel, The Red Badge of Courage (1895), is no longer required reading in American schools, and his other greatest hits—Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893), “The Open Boat” (1897), The Monster (1898), “The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky” (1898), and “The Blue Hotel” (1898)—have fallen out of the cultural conversation.