Sunlight

I’m utterly helpless.

I’ll just have to swallow my spit

and adversity, too.

But look!

A distinguished visitor deigns to visit

my tiny, north-facing cell.

Not the chief making his rounds, no.

As evening falls, a ray of sunlight.

A gleam no bigger than a crumpled postage stamp.

I’m crazy about it! Real first love!

I try to get it to settle on the palm of my hand,

to warm the toes of my shyly bared foot.

Then as I kneel and offer it my undevout, lean face,

in a moment that scrap of sunlight slips away.

After the guest has departed through the bars

the room feels several times colder and darker.

This special cell of a military prison

is like a photographer’s darkroom.

Without any sunlight I laughed like a fool.

One day it was a coffin holding a corpse.

One day it was altogether the sea. How wonderful!

A few people survive here.

Being alive is a sea

without a single sail in sight.

by Ko Un

from Songs for Tomorrow

Green Integer Books, 2009

Now at university in England, Sara looks back on her hometown in southern India. “This is the west,” where almost everything is within reach, but where she comes from, people have always known that “ordinary days can explode without warning, leaving us broken, collecting the scattered pieces of our lives”.

Now at university in England, Sara looks back on her hometown in southern India. “This is the west,” where almost everything is within reach, but where she comes from, people have always known that “ordinary days can explode without warning, leaving us broken, collecting the scattered pieces of our lives”.  The dragon resting on its golden hoard. The gallant knight charging to rescue the maiden from the scaly beast. These are images long associated with the European Middle Ages, yet most (all) medieval people went their whole lives without meeting even a single winged, fire-breathing behemoth. Dragons and other monsters, nights dark and full of terror, lurked largely in the domain of stories—tales, filtered through the intervening centuries and our own interests, that remain with us today.

The dragon resting on its golden hoard. The gallant knight charging to rescue the maiden from the scaly beast. These are images long associated with the European Middle Ages, yet most (all) medieval people went their whole lives without meeting even a single winged, fire-breathing behemoth. Dragons and other monsters, nights dark and full of terror, lurked largely in the domain of stories—tales, filtered through the intervening centuries and our own interests, that remain with us today. A man is standing on the parapet of a bridge. He is about to jump. What should you do? Most people would agree that the moral act would be to talk to him to try to persuade him not to. Most people would also agree that giving him a push because “that’s what he wanted” would be committing murder.

A man is standing on the parapet of a bridge. He is about to jump. What should you do? Most people would agree that the moral act would be to talk to him to try to persuade him not to. Most people would also agree that giving him a push because “that’s what he wanted” would be committing murder. People have relied on the modern horse to plow fields, charge into battle and traverse long distances for millennia. Horses have transformed human societies with every stride. But scientists have struggled to answer the seemingly simple of question of when and where these animals were domesticated.

People have relied on the modern horse to plow fields, charge into battle and traverse long distances for millennia. Horses have transformed human societies with every stride. But scientists have struggled to answer the seemingly simple of question of when and where these animals were domesticated. In June, the Hungarian parliament voted overwhelmingly to eliminate from public schools all teaching related to “homosexuality and gender change”, associating LGBTQI rights and education with pedophilia and totalitarian cultural politics. In late May, Danish MPs passed a resolution against “excessive activism” in academic research environments, including gender studies, race theory, postcolonial and immigration studies in their list of culprits. In December 2020, the supreme court in Romania struck down a law that would have forbidden the teaching of “gender identity theory” but the debate there rages on. Trans-free spaces in Poland have been declared by transphobes eager to purify Poland of corrosive cultural influences from the US and the UK. Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul convention in March sent shudders through the EU, since one of its main objections was the inclusion of protections for women and children against violence, and this “problem” was linked to the foreign word, “gender”.

In June, the Hungarian parliament voted overwhelmingly to eliminate from public schools all teaching related to “homosexuality and gender change”, associating LGBTQI rights and education with pedophilia and totalitarian cultural politics. In late May, Danish MPs passed a resolution against “excessive activism” in academic research environments, including gender studies, race theory, postcolonial and immigration studies in their list of culprits. In December 2020, the supreme court in Romania struck down a law that would have forbidden the teaching of “gender identity theory” but the debate there rages on. Trans-free spaces in Poland have been declared by transphobes eager to purify Poland of corrosive cultural influences from the US and the UK. Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul convention in March sent shudders through the EU, since one of its main objections was the inclusion of protections for women and children against violence, and this “problem” was linked to the foreign word, “gender”. What is perhaps Cage’s most famous work, 4′33″, consists of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, and, like a shack on the edge of a transcendental pond (or the idea of one), 4′33″ is a framework, one that reminds me of the way Walden’s structure positions us to hear not just the sound of the wind at the pond but the sound of the wind vibrating the telegraph lines that ran across the edge of Walden’s mostly felled woods, the sound of man-moved sand shifting down the railroad embankment as ice thawed in spring. The world is animate in Walden, Thoreau word-painting what was invisible to the eyes but tangible to the body. I am reminded of Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, heightening the conversation between the visitor and the Great Basin’s sky, and of Charles Burchfield, whose paintings, made in and around Buffalo in the 1940s, don’t depict fields but the feeling of fields, their invisible vibrations. So Thoreau perceived space at the pond, listening to the wind in the telegraph poles, his ear pressed to the pole’s dead wood for sonic transformation—“its very substance transmuted,” he said.

What is perhaps Cage’s most famous work, 4′33″, consists of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, and, like a shack on the edge of a transcendental pond (or the idea of one), 4′33″ is a framework, one that reminds me of the way Walden’s structure positions us to hear not just the sound of the wind at the pond but the sound of the wind vibrating the telegraph lines that ran across the edge of Walden’s mostly felled woods, the sound of man-moved sand shifting down the railroad embankment as ice thawed in spring. The world is animate in Walden, Thoreau word-painting what was invisible to the eyes but tangible to the body. I am reminded of Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, heightening the conversation between the visitor and the Great Basin’s sky, and of Charles Burchfield, whose paintings, made in and around Buffalo in the 1940s, don’t depict fields but the feeling of fields, their invisible vibrations. So Thoreau perceived space at the pond, listening to the wind in the telegraph poles, his ear pressed to the pole’s dead wood for sonic transformation—“its very substance transmuted,” he said. Anthony Hecht had a daunting formality. He took a measured, classical approach to poetry that, at face value, could seem emotionally cool and intellectually distanced. It was easy to misunderstand his mannered approach to the lyric in the increasingly raucous world of American poetry of the 1960s and after. I liked him immediately when I met him in the early ’80s, but his demeanor put me in mind of T. S. Eliot, who, by all accounts, spoke with a dry, faintly concocted accent and always dressed as if he were going to High Church. As a Jewish American poet, there was a certain anxiety that shadowed Hecht’s style, a fear of exclusion, which he covered up with cunning wit and cultivated shine. He was an exceptional formal poet, like Richard Wilbur and James Merrill, with whom he is often grouped, but he was also a formalist with a difference.

Anthony Hecht had a daunting formality. He took a measured, classical approach to poetry that, at face value, could seem emotionally cool and intellectually distanced. It was easy to misunderstand his mannered approach to the lyric in the increasingly raucous world of American poetry of the 1960s and after. I liked him immediately when I met him in the early ’80s, but his demeanor put me in mind of T. S. Eliot, who, by all accounts, spoke with a dry, faintly concocted accent and always dressed as if he were going to High Church. As a Jewish American poet, there was a certain anxiety that shadowed Hecht’s style, a fear of exclusion, which he covered up with cunning wit and cultivated shine. He was an exceptional formal poet, like Richard Wilbur and James Merrill, with whom he is often grouped, but he was also a formalist with a difference. Springtime on the West African coast. Nights, pleasantly warm and close, give way to searing daylight. By ten o’clock, the sun presses down upon the earth like a thumb, grinding everything beneath it into the dust that rises from the roads and thickens the air. It is a heat that hurts. People hide in the shade of mango trees or within the dark caverns of roadside shops; movement encourages a torrent of sweat.

Springtime on the West African coast. Nights, pleasantly warm and close, give way to searing daylight. By ten o’clock, the sun presses down upon the earth like a thumb, grinding everything beneath it into the dust that rises from the roads and thickens the air. It is a heat that hurts. People hide in the shade of mango trees or within the dark caverns of roadside shops; movement encourages a torrent of sweat. If you tend to click on those trend pieces telling us

If you tend to click on those trend pieces telling us  The word ‘economy’ evolved from the Greek root οἶκος. ‘Oikos’ had three interrelated senses in ancient Greece: the family, the family’s land, and the family’s home. These three, taken interchangeably, constituted the first or fundamental political unit in the ancient Greek world, especially in the minds of Greece’s hereditary aristocrats, for whom family mattered more than all other affiliations. The family, then and after, was viewed as the state in miniature, with its rules of order and its exemplars (of moral strength or moral incontinence).

The word ‘economy’ evolved from the Greek root οἶκος. ‘Oikos’ had three interrelated senses in ancient Greece: the family, the family’s land, and the family’s home. These three, taken interchangeably, constituted the first or fundamental political unit in the ancient Greek world, especially in the minds of Greece’s hereditary aristocrats, for whom family mattered more than all other affiliations. The family, then and after, was viewed as the state in miniature, with its rules of order and its exemplars (of moral strength or moral incontinence). T

T City streets seemed eerily empty in the early years of photography. During minutes-long exposures, carriage traffic and even ambling pedestrians blurred into nonexistence. The only subjects that remained were those that stood still: buildings, trees, the road itself. In one famous image, a bootblack and his customer appear to be the lone survivors on a Parisian boulevard. When shorter exposure times were finally possible in the late 1850s, a British photographer marveled: “Views in distant and picturesque cities will not seem plague-stricken, by the deserted aspect of their streets and squares, but will appear alive with the busy throng of their motley populations.”

City streets seemed eerily empty in the early years of photography. During minutes-long exposures, carriage traffic and even ambling pedestrians blurred into nonexistence. The only subjects that remained were those that stood still: buildings, trees, the road itself. In one famous image, a bootblack and his customer appear to be the lone survivors on a Parisian boulevard. When shorter exposure times were finally possible in the late 1850s, a British photographer marveled: “Views in distant and picturesque cities will not seem plague-stricken, by the deserted aspect of their streets and squares, but will appear alive with the busy throng of their motley populations.” Surgeons in New York have successfully attached a kidney grown in a genetically altered pig to a human patient and found that the organ worked normally, a scientific breakthrough that one day may yield a vast new supply of organs for severely ill patients.

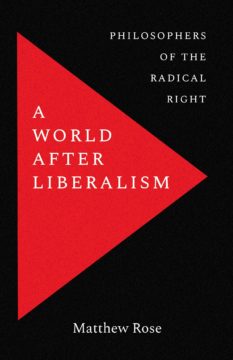

Surgeons in New York have successfully attached a kidney grown in a genetically altered pig to a human patient and found that the organ worked normally, a scientific breakthrough that one day may yield a vast new supply of organs for severely ill patients. Perhaps the most invigorated intellectual movements to gain steam during the Trump era occupied not the progressive left but the reactionary right. The conservative visions of Reagan, Goldwater, or Buckley have now receded into the pages of history, voicing only a whimper of protest. What stands in the wake of these older modes of conservatism is not yet fully determined, but various modes of populism, authoritarianism, nationalism, cable news antagonisms, and conspiracy-driven paranoia now contend for whatever will come next.

Perhaps the most invigorated intellectual movements to gain steam during the Trump era occupied not the progressive left but the reactionary right. The conservative visions of Reagan, Goldwater, or Buckley have now receded into the pages of history, voicing only a whimper of protest. What stands in the wake of these older modes of conservatism is not yet fully determined, but various modes of populism, authoritarianism, nationalism, cable news antagonisms, and conspiracy-driven paranoia now contend for whatever will come next.