Mankind is at least 90% slumber. The rest is history.

……………………………………………..—Roshi Bob

The Inferno -excerpt

—Canto 1

Midway upon the journey of our life

….. I found myself within a forest dark,

….. For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Ah me! How hard a thing it is to say

….. What was this forest savage, rough, and stern,

….. Which in the very thought renews the fear.

So bitter it is, death is little more;

….. But of the good to treat, which there I found,

….. Speak will I of the other things I saw there.

I cannot well repeat how there I entered,

….. So full was I of slumber at the moment

….. In which I had abandoned the true way.

Dante Alighieri

from The Inferno

Barnes & Noble Classics, 2003

Translation: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

R

R In 2017, Karen Kostroff, a renowned oncology surgeon at Northwell Health in the New York Metropolitan area added a new talking point to her standard conversation with breast cancer patients facing tumor removal surgery. These conversations are never easy, because a cancer diagnosis is devastating news. But the new topic seemed to give her patients a sense of purpose, a feeling that their medical misfortune had the potential to do something good for other people.

In 2017, Karen Kostroff, a renowned oncology surgeon at Northwell Health in the New York Metropolitan area added a new talking point to her standard conversation with breast cancer patients facing tumor removal surgery. These conversations are never easy, because a cancer diagnosis is devastating news. But the new topic seemed to give her patients a sense of purpose, a feeling that their medical misfortune had the potential to do something good for other people.  Alex Kane in Jewish Currents:

Alex Kane in Jewish Currents: Daniel J Herman in Aeon:

Daniel J Herman in Aeon: Over at Phenomenal World, Lily Hu interviews Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò on climate crisis, reparations, and the use of history:

Over at Phenomenal World, Lily Hu interviews Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò on climate crisis, reparations, and the use of history: A

A “Private Notebooks: 1914-1916” is a strange and intriguing record — illuminating when it comes to Wittgenstein’s preoccupations, his sexual anguish, his continuous struggles with his “work” in philosophy, along with his intermittent comments about his “job” in the military. (Like other writings by Wittgenstein that have been published posthumously, “Private Notebooks” is a bilingual edition, with German and English printed on facing pages.) Perloff also points out that unlike so many other war diaries, Wittgenstein’s includes very little about the larger stakes of the war itself. One exception is an entry that reads like a startlingly cheerful declaration that his own side was doomed: “The English — the best race in the world — cannot lose! We, however, can lose & will lose, if not this year, then the next!”

“Private Notebooks: 1914-1916” is a strange and intriguing record — illuminating when it comes to Wittgenstein’s preoccupations, his sexual anguish, his continuous struggles with his “work” in philosophy, along with his intermittent comments about his “job” in the military. (Like other writings by Wittgenstein that have been published posthumously, “Private Notebooks” is a bilingual edition, with German and English printed on facing pages.) Perloff also points out that unlike so many other war diaries, Wittgenstein’s includes very little about the larger stakes of the war itself. One exception is an entry that reads like a startlingly cheerful declaration that his own side was doomed: “The English — the best race in the world — cannot lose! We, however, can lose & will lose, if not this year, then the next!”

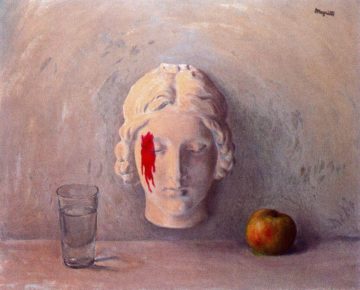

A work of art has the power to transport its viewer to another time and place. Now, the

A work of art has the power to transport its viewer to another time and place. Now, the  Policies to make police forces more representative of communities have centered on race. But race may crudely proxy views and lived experiences, undermining classic theories of representative bureaucracy. To conduct a multi-dimensional analysis, we merge personnel records, voter files and census data to examine roughly 220,000 officers from 97 of the 100 largest local U.S. agencies—over one third of local law enforcement agents nationwide. We show officers skew more White, Republican, politically active, male, and high-income than their jurisdictions; they also surround themselves with similarly unrepresentative neighbors. In a quasi-experimental analysis in Chicago, we find Democratic and minority officers initiate fewer stops, arrests, and uses of force than Republican and White counterparts facing common circumstances. The Black-White behavioral gap is often far larger than the Democratic-Republican gap, a pattern not observed among Hispanic officers. Our results complicate conventional understandings of descriptive representation, highlighting the importance of multi-dimensional perspectives of diversity.

Policies to make police forces more representative of communities have centered on race. But race may crudely proxy views and lived experiences, undermining classic theories of representative bureaucracy. To conduct a multi-dimensional analysis, we merge personnel records, voter files and census data to examine roughly 220,000 officers from 97 of the 100 largest local U.S. agencies—over one third of local law enforcement agents nationwide. We show officers skew more White, Republican, politically active, male, and high-income than their jurisdictions; they also surround themselves with similarly unrepresentative neighbors. In a quasi-experimental analysis in Chicago, we find Democratic and minority officers initiate fewer stops, arrests, and uses of force than Republican and White counterparts facing common circumstances. The Black-White behavioral gap is often far larger than the Democratic-Republican gap, a pattern not observed among Hispanic officers. Our results complicate conventional understandings of descriptive representation, highlighting the importance of multi-dimensional perspectives of diversity. Over the past 60 years, the standard model (SM) has established itself as the most successful theory of matter and fundamental interactions—to date. The 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson only added to the streak of triumphs for the theory (

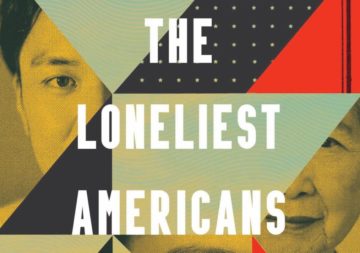

Over the past 60 years, the standard model (SM) has established itself as the most successful theory of matter and fundamental interactions—to date. The 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson only added to the streak of triumphs for the theory ( One of the most revealing features of the reckoning prompted by the recent horrific attacks on Asians in the United States is the diversity of responses offered by Asian Americans themselves. Undermining the racialized presumption that “Asian Americans” form a homogeneous group, these conflicting views reveal the sociopolitical stratification of some

One of the most revealing features of the reckoning prompted by the recent horrific attacks on Asians in the United States is the diversity of responses offered by Asian Americans themselves. Undermining the racialized presumption that “Asian Americans” form a homogeneous group, these conflicting views reveal the sociopolitical stratification of some  Does banishing convention from the schemas with which we formulate our manners and moods allow us, as DeWitt’s fictions seem to suggest, to transcend systemic bullshit? In recounting to Lorentzen the frustrations of her literary career, DeWitt compared the irrationality of editors to that of Plato’s Thrasymachus, Callicles, and Gorgias, “sophists who sulk whenever Socrates frustrates their conventional arguments.” If conventions are by their nature arbitrary, and reason is by nature orderly, one might be forgiven for thinking it follows that convention is an enemy of reason. And if reason constitutes our sole path to veracity, one might be forgiven for thinking it follows that convention is an enemy of truth. Occasionally I do wonder if my lust for the convention of financial security invalidates and renders irrational my equally convention-based claims that my work is “all very exciting.” If I have followed the convention of rising through the ranks of employment, a convenience in exchange for which my mind must descend into bullshit, does this render me unavoidably irrational? Does it make me an enemy of truth?

Does banishing convention from the schemas with which we formulate our manners and moods allow us, as DeWitt’s fictions seem to suggest, to transcend systemic bullshit? In recounting to Lorentzen the frustrations of her literary career, DeWitt compared the irrationality of editors to that of Plato’s Thrasymachus, Callicles, and Gorgias, “sophists who sulk whenever Socrates frustrates their conventional arguments.” If conventions are by their nature arbitrary, and reason is by nature orderly, one might be forgiven for thinking it follows that convention is an enemy of reason. And if reason constitutes our sole path to veracity, one might be forgiven for thinking it follows that convention is an enemy of truth. Occasionally I do wonder if my lust for the convention of financial security invalidates and renders irrational my equally convention-based claims that my work is “all very exciting.” If I have followed the convention of rising through the ranks of employment, a convenience in exchange for which my mind must descend into bullshit, does this render me unavoidably irrational? Does it make me an enemy of truth? Much of “Wet Leg” addresses the banality of adulthood, and particularly the discombobulating stretch between youth and middle age—from twenty-five to forty, say. (Teasdale is twenty-nine and Chambers is twenty-eight.) In the video for “Too Late Now,” Teasdale and Chambers stumble around in striped bathrobes with cucumber slices over their eyes. A montage gathers some of the more aesthetically unpleasant elements of modern life: cranes, a cigarette butt, Botox, trash spilling from an overstuffed dumpster, graffiti wishing passersby a shit day, fluorescent lights, a pigeon. “I’m not sure if this is the kinda life that I saw myself living,” Teasdale admits. A synthesizer rings out like church bells. Though she never sounds especially devastated, “Too Late Now” is Teasdale’s most tender and revealing vocal performance, and one of the best and most dynamic songs on “Wet Leg.” As children, we’re often desperate to grow up, yet it turns out that adulthood can be ugly and depressing.

Much of “Wet Leg” addresses the banality of adulthood, and particularly the discombobulating stretch between youth and middle age—from twenty-five to forty, say. (Teasdale is twenty-nine and Chambers is twenty-eight.) In the video for “Too Late Now,” Teasdale and Chambers stumble around in striped bathrobes with cucumber slices over their eyes. A montage gathers some of the more aesthetically unpleasant elements of modern life: cranes, a cigarette butt, Botox, trash spilling from an overstuffed dumpster, graffiti wishing passersby a shit day, fluorescent lights, a pigeon. “I’m not sure if this is the kinda life that I saw myself living,” Teasdale admits. A synthesizer rings out like church bells. Though she never sounds especially devastated, “Too Late Now” is Teasdale’s most tender and revealing vocal performance, and one of the best and most dynamic songs on “Wet Leg.” As children, we’re often desperate to grow up, yet it turns out that adulthood can be ugly and depressing.