Prabir Purkayastha in CounterPunch:

Do the Ukraine war and the action of the United States, the EU and the UK spell the end of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency? Even with the peace talks recently held in Turkey or the proposed 15-point peace plan, as the Financial Times had reported earlier, the fallout for the dollar still remains. For the first time, Russia, a major nuclear power and economy, was treated as a vassal state, with the United States, the EU and the UK seizing its $300 billion foreign exchange reserves. Where does this leave other countries, who also hold their foreign exchange reserves largely in dollars or euros?

Do the Ukraine war and the action of the United States, the EU and the UK spell the end of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency? Even with the peace talks recently held in Turkey or the proposed 15-point peace plan, as the Financial Times had reported earlier, the fallout for the dollar still remains. For the first time, Russia, a major nuclear power and economy, was treated as a vassal state, with the United States, the EU and the UK seizing its $300 billion foreign exchange reserves. Where does this leave other countries, who also hold their foreign exchange reserves largely in dollars or euros?

The threat to the dollar hegemony is only one part of the fallout. The complex supply chains, built on the premise of a stable trading regime of the World Trade Organization principles, are also threatening to unravel. The United States is discovering that Russia is not simply a petrostate as they thought but that it also supplies many of the critical materials that the U.S. needs for several industries as well as its military. This is apart from the fact that Russia is also a major supplier of wheat and fertilizers.

More here.

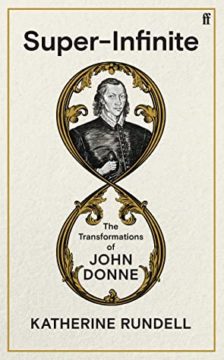

The agility of Donne’s imagination and the sheer pyrotechnic weirdness of his writings have made him both irresistibly attractive to biographers – who wouldn’t want to understand the man behind poems like this? – and particularly elusive of biographical scrutiny: what set of facts could possibly help to explain such a person? Katherine Rundell’s excellent Super-Infinite approaches Donne with keen and frank awareness of these temptations and the pitfalls they conceal. She recognises the double bind in which Donne’s works place his readers: they are conspicuously difficult and erudite, demanding depth of knowledge, intensity of attention and speed of thought from those who would follow them, but bringing knowledge to bear upon their quicksilver shifts and spurts of imagination can feel like ramming a pin through the body of a particularly beautiful butterfly in order to taxonomise it. Rundell is scrupulously polite about R C Bald’s ‘spectacularly detailed’ life of Donne, the standard scholarly biography, calling it ‘the bedrock of this book’ in a footnote, but there has surely never been a duller life of a more exciting poet. Knowledge may be necessary, but it can be like an anvil dropped on the head of a mischievous cartoon character, stunning it briefly into passive silence.

The agility of Donne’s imagination and the sheer pyrotechnic weirdness of his writings have made him both irresistibly attractive to biographers – who wouldn’t want to understand the man behind poems like this? – and particularly elusive of biographical scrutiny: what set of facts could possibly help to explain such a person? Katherine Rundell’s excellent Super-Infinite approaches Donne with keen and frank awareness of these temptations and the pitfalls they conceal. She recognises the double bind in which Donne’s works place his readers: they are conspicuously difficult and erudite, demanding depth of knowledge, intensity of attention and speed of thought from those who would follow them, but bringing knowledge to bear upon their quicksilver shifts and spurts of imagination can feel like ramming a pin through the body of a particularly beautiful butterfly in order to taxonomise it. Rundell is scrupulously polite about R C Bald’s ‘spectacularly detailed’ life of Donne, the standard scholarly biography, calling it ‘the bedrock of this book’ in a footnote, but there has surely never been a duller life of a more exciting poet. Knowledge may be necessary, but it can be like an anvil dropped on the head of a mischievous cartoon character, stunning it briefly into passive silence. Reading was Richard’s primary occupation. His New York apartment was covered in books, floor to ceiling, interrupted only by a desk, a few places to sit, a bed in a book-lined alcove (which was also home to Mildred, Richard’s life-size stuffed gorilla), and the bathroom, adorned with dozens of small portraits of famous writers, glaring at anyone who dared use the toilet. The kitchen was an afterthought—mostly a place to store kibble for Gide, his eccentric French bulldog, since Richard almost always ate out. I used to care for Gide when Richard traveled, so I was once there on his return from a trip to Europe with his husband, the artist David Alexander; the souvenir Richard was most excited to show off was a gargantuan copy—I think in French, though perhaps in the original Italian—of Leopardi’s Zibaldone, which had not yet been translated into English in its entirety. Finally he could read it! New books were among the major events of his life. By his door was always a growing stack of books to sell to the Strand; at some point David had introduced the rule that for every new book that came in, one had to go out.

Reading was Richard’s primary occupation. His New York apartment was covered in books, floor to ceiling, interrupted only by a desk, a few places to sit, a bed in a book-lined alcove (which was also home to Mildred, Richard’s life-size stuffed gorilla), and the bathroom, adorned with dozens of small portraits of famous writers, glaring at anyone who dared use the toilet. The kitchen was an afterthought—mostly a place to store kibble for Gide, his eccentric French bulldog, since Richard almost always ate out. I used to care for Gide when Richard traveled, so I was once there on his return from a trip to Europe with his husband, the artist David Alexander; the souvenir Richard was most excited to show off was a gargantuan copy—I think in French, though perhaps in the original Italian—of Leopardi’s Zibaldone, which had not yet been translated into English in its entirety. Finally he could read it! New books were among the major events of his life. By his door was always a growing stack of books to sell to the Strand; at some point David had introduced the rule that for every new book that came in, one had to go out. “Within a few years owning a car,” writes Bryan Appleyard in this entertainingly forthright history, “might seem as eccentric as owning a train or a bus. Or perhaps it will simply be illegal.” Although Appleyard’s intention is to document a way of life that he believes is passing, his book is not a lament or a eulogy, nor really a celebration, but instead an acknowledgment of the extraordinary cultural and environmental impact the car has had on this planet in the last 135-plus years.

“Within a few years owning a car,” writes Bryan Appleyard in this entertainingly forthright history, “might seem as eccentric as owning a train or a bus. Or perhaps it will simply be illegal.” Although Appleyard’s intention is to document a way of life that he believes is passing, his book is not a lament or a eulogy, nor really a celebration, but instead an acknowledgment of the extraordinary cultural and environmental impact the car has had on this planet in the last 135-plus years. The tank looked empty, but turning over a shell revealed a hidden octopus no bigger than a Ping-Pong ball. She didn’t move. Then all at once, she stretched her ruffled arms as her skin changed from pearly beige to a pattern of vivid bronze stripes. “She’s trying to talk with us,” said Bret Grasse, manager of cephalopod operations at the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international research center in Woods Hole, Mass., in the southwestern corner of Cape Cod.

The tank looked empty, but turning over a shell revealed a hidden octopus no bigger than a Ping-Pong ball. She didn’t move. Then all at once, she stretched her ruffled arms as her skin changed from pearly beige to a pattern of vivid bronze stripes. “She’s trying to talk with us,” said Bret Grasse, manager of cephalopod operations at the Marine Biological Laboratory, an international research center in Woods Hole, Mass., in the southwestern corner of Cape Cod. A glance at Hobson-Jobson, the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words in use during the British rule in India, will show that the word “loot” comes into English from Hindi, ultimately deriving from Sanskrit. It entered the English language around the time of the Opium Wars, when the British were not just in India but also in China. This was when the 8th Earl of Elgin, James Bruce, was present at the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. He was, incidentally, the son of the 7th Lord Elgin who removed the marbles from the Parthenon. James Bruce had this to say about loot:

A glance at Hobson-Jobson, the historical dictionary of Anglo-Indian words in use during the British rule in India, will show that the word “loot” comes into English from Hindi, ultimately deriving from Sanskrit. It entered the English language around the time of the Opium Wars, when the British were not just in India but also in China. This was when the 8th Earl of Elgin, James Bruce, was present at the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. He was, incidentally, the son of the 7th Lord Elgin who removed the marbles from the Parthenon. James Bruce had this to say about loot: Languages change continually and in wide variety of ways. New words and phrases appear, while others fall into disuse. Words subtly, or less subtly, shift their meanings or develop new meanings, while speech sounds and intonation change continually. Yet perhaps the most fundamental shift in language change is gradual conventionalization: patterns of communication are initially flexible, but over time they slowly become increasingly stable, conventionalized, and, in many cases, obligatory. This is spontaneous order in action: from an initial jumble increasingly specific patterns emerge over time.

Languages change continually and in wide variety of ways. New words and phrases appear, while others fall into disuse. Words subtly, or less subtly, shift their meanings or develop new meanings, while speech sounds and intonation change continually. Yet perhaps the most fundamental shift in language change is gradual conventionalization: patterns of communication are initially flexible, but over time they slowly become increasingly stable, conventionalized, and, in many cases, obligatory. This is spontaneous order in action: from an initial jumble increasingly specific patterns emerge over time. Antonio Gramsci’s near-feral Sardinian childhood set him apart from most other leading communist revolutionaries of the interwar years, who tended to originate in cities. His father was imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy; his mother scraped by a living mending clothes. When Gramsci was four, a boil on his back began hemorrhaging, and he nearly bled to death. His mother bought a shroud and a small coffin, which stood in a corner of the house for the rest of his youth.

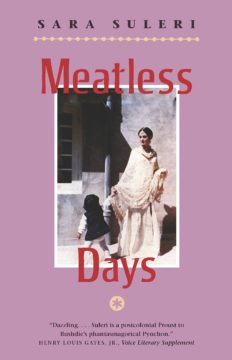

Antonio Gramsci’s near-feral Sardinian childhood set him apart from most other leading communist revolutionaries of the interwar years, who tended to originate in cities. His father was imprisoned for petty embezzling as a state functionary in the Kingdom of Italy; his mother scraped by a living mending clothes. When Gramsci was four, a boil on his back began hemorrhaging, and he nearly bled to death. His mother bought a shroud and a small coffin, which stood in a corner of the house for the rest of his youth. My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.”

My friend Professor Tahira Naqvi wrote in her condolence note: “I don’t think there is a book cover that has ever made a place in popular consciousness as that of Meatless Days. I can’t remember a book from my early days here that had as much of an impact as that brilliantly written memoir.” Why do people at the top of their careers snap and make wildly self-destructive moves that rip apart everything they have been working to build? In a blink, Will Smith went from Mr. Nice Guy on the verge of winning an Oscar to a crazed assailant in Satan’s grip. “At your highest moment, be careful. That’s when the devil comes for you,” Smith said in his acceptance speech, quoting what Denzel Washington told him minutes earlier to calm him down.

Why do people at the top of their careers snap and make wildly self-destructive moves that rip apart everything they have been working to build? In a blink, Will Smith went from Mr. Nice Guy on the verge of winning an Oscar to a crazed assailant in Satan’s grip. “At your highest moment, be careful. That’s when the devil comes for you,” Smith said in his acceptance speech, quoting what Denzel Washington told him minutes earlier to calm him down. In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them.

In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them. J

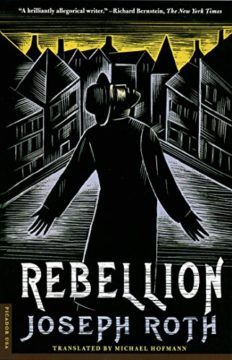

J Roth’s most securely canonical work is

Roth’s most securely canonical work is