Maria Rubin in The NY Review of Books:

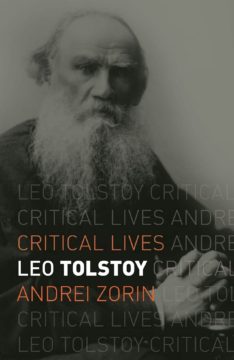

IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment.

IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment.

Zorin’s book achieves the ultimate expectation set by the biography genre — he creates a consistent representation of Tolstoy’s integral personality. To begin with, he does not revisit the familiar dichotomy of Tolstoy the artist versus Tolstoy the thinker. According to this narrative, the writer turned to excessive moralizing after completing War and Peace and Anna Karenina, gradually suffocating his artistic genius. In the colorful words of Tatyana Tolstaya, the writer’s distant descendent and a popular author in her own right, once he turned to preaching the “quill fell out of his hand.” Tolstoy himself was very much aware of this inner conflict and in later life “resolved” it by condemning much of European art and literature, his own fiction included. Whereas many scholars have been all too eager to assimilate this binary paradigm, Zorin writes his biography against that trend. He presents Tolstoy as a sum total of all of his various activities — fiction, nonfiction, correspondence, oral teachings, religious writings, direct action, and even family squabbles — seamlessly integrated into the text of his life. While Tolstoy’s path seems full of unexpected shifts from one extreme to the other (from a dissolute lifestyle to near-chastity, from hunting to vegetarianism, from fiction to preaching, from luxury to asceticism), Zorin’s book shows that every juncture was just another manifestation of the inner logic of his existence. In this light, the spiritual crisis of 1878, when Tolstoy appeared to have rejected nearly all of his former values, was nothing sudden: this “conversion” became a culmination of a lifelong quest for the meaning of life and death, deep self-reflection and religious skepticism.

More here.

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven in Aeon:

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven in Aeon: Ajay Singh Chaudhary in Late Light:

Ajay Singh Chaudhary in Late Light: Lee Harris in Phenomenal World:

Lee Harris in Phenomenal World: R

R Instead of following the well-worn path of thinking about Abraham as the father of a nation, we are presented with a traveling herder about whom we know nothing other than that he had a beautiful wife. Calasso points out that among “the many causes of bafflement scholars come up against in the Bible one of the most glaring is the fact that there are three occasions in Genesis when a man tries to pass off his wife as his sister.” Recalling these episodes alongside the accounts of fathers willing to send out their daughters to be raped by mobs casts these men in rather unflattering light. But more importantly, it raises the question of how the books of the Bible were assembled, how and why stories were included or deleted. The “main author of the Bible,” writes Calasso, “could be thought of as the unknown Final Redactor, who thus becomes responsible for all the innumerable occasions of perplexity that the Bible is bound to provoke in anyone.” This seems to be the interpretative crux. The Bible continues to inspire our cultural and religious imaginary. The question is not whether to read it — it is how we read it.

Instead of following the well-worn path of thinking about Abraham as the father of a nation, we are presented with a traveling herder about whom we know nothing other than that he had a beautiful wife. Calasso points out that among “the many causes of bafflement scholars come up against in the Bible one of the most glaring is the fact that there are three occasions in Genesis when a man tries to pass off his wife as his sister.” Recalling these episodes alongside the accounts of fathers willing to send out their daughters to be raped by mobs casts these men in rather unflattering light. But more importantly, it raises the question of how the books of the Bible were assembled, how and why stories were included or deleted. The “main author of the Bible,” writes Calasso, “could be thought of as the unknown Final Redactor, who thus becomes responsible for all the innumerable occasions of perplexity that the Bible is bound to provoke in anyone.” This seems to be the interpretative crux. The Bible continues to inspire our cultural and religious imaginary. The question is not whether to read it — it is how we read it. Lake Mary Jane is shallow—twelve feet deep at most—but she’s well connected. She makes her home in central Florida, in an area that was once given over to wetlands. To the north, she is linked to a marsh, and to the west a canal ties her to Lake Hart. To the south, through more canals, Mary Jane feeds into a chain of lakes that run into Lake Kissimmee, which feeds into Lake Okeechobee. Were Lake Okeechobee not encircled by dikes, the water that flows through Mary Jane would keep pouring south until it glided across the Everglades and out to sea.

Lake Mary Jane is shallow—twelve feet deep at most—but she’s well connected. She makes her home in central Florida, in an area that was once given over to wetlands. To the north, she is linked to a marsh, and to the west a canal ties her to Lake Hart. To the south, through more canals, Mary Jane feeds into a chain of lakes that run into Lake Kissimmee, which feeds into Lake Okeechobee. Were Lake Okeechobee not encircled by dikes, the water that flows through Mary Jane would keep pouring south until it glided across the Everglades and out to sea. A

A Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin.

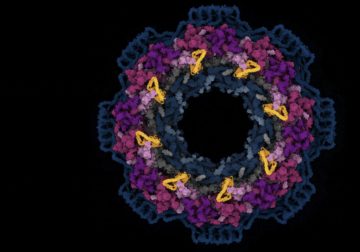

Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin. For more than a decade, molecular biologist Martin Beck and his colleagues have been trying to piece together one of the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzles: a detailed model of the largest molecular machine in human cells.

For more than a decade, molecular biologist Martin Beck and his colleagues have been trying to piece together one of the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzles: a detailed model of the largest molecular machine in human cells. If one wishes to be exposed to news, information or perspective that contravenes the prevailing US/NATO view on the war in Ukraine, a rigorous search is required. And there is no guarantee that search will succeed. That is because the state/corporate censorship regime that has been imposed in the West with regard to this war is stunningly aggressive, rapid and comprehensive.

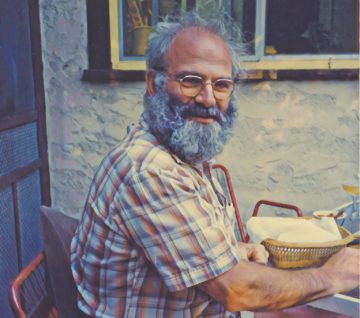

If one wishes to be exposed to news, information or perspective that contravenes the prevailing US/NATO view on the war in Ukraine, a rigorous search is required. And there is no guarantee that search will succeed. That is because the state/corporate censorship regime that has been imposed in the West with regard to this war is stunningly aggressive, rapid and comprehensive. Haven draws on a compendious knowledge of her subject, having mused on and written about Miłosz for more than 20 years. She met with the man himself on two occasions in early 2000, visits that turned out to be his last interviews in the United States, and since then she has talked with his translators, including Robert Hass, Lillian Vallee, and Peter Dale Scott; his family, including his son, Anthony, and his brother-in-law, Bill Thigpen; and his friends, including Mark Danner, who purchased Miłosz’s longtime home on Grizzly Peak. She has also edited two prior volumes on Miłosz, one collection of interviews and one of essays; has penned dozens of blog posts relating to him on her fecund

Haven draws on a compendious knowledge of her subject, having mused on and written about Miłosz for more than 20 years. She met with the man himself on two occasions in early 2000, visits that turned out to be his last interviews in the United States, and since then she has talked with his translators, including Robert Hass, Lillian Vallee, and Peter Dale Scott; his family, including his son, Anthony, and his brother-in-law, Bill Thigpen; and his friends, including Mark Danner, who purchased Miłosz’s longtime home on Grizzly Peak. She has also edited two prior volumes on Miłosz, one collection of interviews and one of essays; has penned dozens of blog posts relating to him on her fecund  In 1968, Yvonne Rainer wrote an essay criticizing “much of the western dancing we are familiar with” for the way in which, in any given “phrase,” the “focus of attention” is “the part that is the most still” and that registers “like a photograph.”

In 1968, Yvonne Rainer wrote an essay criticizing “much of the western dancing we are familiar with” for the way in which, in any given “phrase,” the “focus of attention” is “the part that is the most still” and that registers “like a photograph.”