Roger Pielke, Jr. in The New Atlantis:

In a recent interview in New York Times Magazine, energy expert and polymath Vaclav Smil found himself being pressured by his interviewer to acknowledge that climate change was either a catastrophe or not a problem. The famously cantankerous Smil bristled at the framing: “I cannot tell you that we don’t have a problem because we do have a problem. But I cannot tell you it’s the end of the world by next Monday because it is not the end of the world by next Monday. What’s the point of you pressing me to belong to one of these groups?”

In a recent interview in New York Times Magazine, energy expert and polymath Vaclav Smil found himself being pressured by his interviewer to acknowledge that climate change was either a catastrophe or not a problem. The famously cantankerous Smil bristled at the framing: “I cannot tell you that we don’t have a problem because we do have a problem. But I cannot tell you it’s the end of the world by next Monday because it is not the end of the world by next Monday. What’s the point of you pressing me to belong to one of these groups?”

For well over a decade, the American debate over climate change has largely been a battle between two extremes: those who view climate change apocalyptically, and those castigated as deniers of climate science. In institutions of science and in the mainstream media, we see the celebration of the catastrophists and the denigration of the deniers. Predictably, the categories map neatly onto the extremes of left-versus-right politics.

More here.

Pretexts:

Pretexts: Researchers in the Biomedical Engineering Department at UConn have developed a new cardiac cell-derived platform that closely mimics the human heart, unlocking potential for more thorough preclinical drug development and testing, and model for cardiac diseases. The research, published in Cell Reports by Assistant Professor Kshitiz in collaboration with Dr. Junaid Afzal in the cardiology department at the University of California San Francisco, presents a method that accelerates maturation of human cardiac cells towards a state suitable enough to be a surrogate for preclinical drug testing.

Researchers in the Biomedical Engineering Department at UConn have developed a new cardiac cell-derived platform that closely mimics the human heart, unlocking potential for more thorough preclinical drug development and testing, and model for cardiac diseases. The research, published in Cell Reports by Assistant Professor Kshitiz in collaboration with Dr. Junaid Afzal in the cardiology department at the University of California San Francisco, presents a method that accelerates maturation of human cardiac cells towards a state suitable enough to be a surrogate for preclinical drug testing. Around you, there is piracy and chaos. But you’re enterprising, and keep to your path. At university, you hardly sleep, and you eat what you can afford. Why do you work yourself this way? It’s not as if you’re getting paid for it. Another version of yourself, in another time, though, is. Now, living in the California sun with some success, you reflect on your poor, wan, sleepless younger self and feel a wave of gratitude, and then of prickly regret. The kid you were had different dreams; it strikes you as unfair that you sit pretty on the spoils of that person’s efforts. If you could take some of your wealth and send it backward in time, to your younger self, you would.

Around you, there is piracy and chaos. But you’re enterprising, and keep to your path. At university, you hardly sleep, and you eat what you can afford. Why do you work yourself this way? It’s not as if you’re getting paid for it. Another version of yourself, in another time, though, is. Now, living in the California sun with some success, you reflect on your poor, wan, sleepless younger self and feel a wave of gratitude, and then of prickly regret. The kid you were had different dreams; it strikes you as unfair that you sit pretty on the spoils of that person’s efforts. If you could take some of your wealth and send it backward in time, to your younger self, you would. Intellectual histories of recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “

Intellectual histories of recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “ In 1868, the mathematician Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll) proclaimed that an encryption scheme called the Vigenère cipher was “unbreakable.” He had no proof, but he had compelling reasons for his belief, since mathematicians had been trying unsuccessfully to break the cipher for more than three centuries.

In 1868, the mathematician Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll) proclaimed that an encryption scheme called the Vigenère cipher was “unbreakable.” He had no proof, but he had compelling reasons for his belief, since mathematicians had been trying unsuccessfully to break the cipher for more than three centuries. The scientist James Lovelock’s discoveries had an immense influence on our understanding of the global impact of humankind, and on the search for extraterrestrial life. A vigorous writer and speaker, he became a hero to the green movement, although he was one of its most formidable critics.

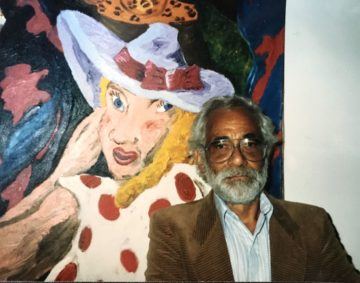

The scientist James Lovelock’s discoveries had an immense influence on our understanding of the global impact of humankind, and on the search for extraterrestrial life. A vigorous writer and speaker, he became a hero to the green movement, although he was one of its most formidable critics. “Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott,” a clamorous retrospective at the New Museum, bodes to be enjoyed by practically everyone who sees it, though some may be nagged by inklings that they shouldn’t. For more than three decades, until he was slowed by health ailments in the two-thousands—he died in 2009, at the age of eighty-three—the impetuous figurative painter danced across minefields of racial and sexual provocation, celebrating libertine romance and cannibalizing canonical art history by way of appreciative parody. He was born in California, the son of musicians from New Orleans. His mother, certainly, and possibly his father, who worked as a railroad waiter, had enslaved ancestors, but both of them—and Colescott—could pass for white. As Matthew Weseley, the co-curator of the show with Lowery Stokes Sims, recounts in the splendid catalogue, Colescott’s mother insisted on the ruse, which he adopted. The mild-mannered modernism of his early works, sampled at the New Museum, affords no hints to the contrary.

“Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott,” a clamorous retrospective at the New Museum, bodes to be enjoyed by practically everyone who sees it, though some may be nagged by inklings that they shouldn’t. For more than three decades, until he was slowed by health ailments in the two-thousands—he died in 2009, at the age of eighty-three—the impetuous figurative painter danced across minefields of racial and sexual provocation, celebrating libertine romance and cannibalizing canonical art history by way of appreciative parody. He was born in California, the son of musicians from New Orleans. His mother, certainly, and possibly his father, who worked as a railroad waiter, had enslaved ancestors, but both of them—and Colescott—could pass for white. As Matthew Weseley, the co-curator of the show with Lowery Stokes Sims, recounts in the splendid catalogue, Colescott’s mother insisted on the ruse, which he adopted. The mild-mannered modernism of his early works, sampled at the New Museum, affords no hints to the contrary. Sūnya, nulla, ṣifr, zevero, zip and zilch are among the many names of the mathematical concept of nothingness. Historians, journalists and others have variously identified the symbol’s birthplace as the Andes mountains of South America, the flood plains of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, the surface of a calculating board in the Tang dynasty of China, a cast iron column and temple inscriptions in India, and most recently, a stone epigraphic inscription found in Cambodia.

Sūnya, nulla, ṣifr, zevero, zip and zilch are among the many names of the mathematical concept of nothingness. Historians, journalists and others have variously identified the symbol’s birthplace as the Andes mountains of South America, the flood plains of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, the surface of a calculating board in the Tang dynasty of China, a cast iron column and temple inscriptions in India, and most recently, a stone epigraphic inscription found in Cambodia. The Green New Deal is so dead that uttering the name now sounds like a bitter joke. Other ambitious plans like Jay Inslee’s were ignored. Biden’s more realistic plan was killed by Joe Manchin. Polls like the one that Wallace-Wells cite above

The Green New Deal is so dead that uttering the name now sounds like a bitter joke. Other ambitious plans like Jay Inslee’s were ignored. Biden’s more realistic plan was killed by Joe Manchin. Polls like the one that Wallace-Wells cite above  While I defend the existence and utility of IQ and its principal component, general intelligence or g, in the study of individual differences, I think it’s completely irrelevant to AI, AI scaling, and AI safety. It’s a measure of differences among humans within the restricted range they occupy, developed more than a century ago. It’s a statistical construct with no theoretical foundation, and it has tenuous connections to any mechanistic understanding of cognition other than as an omnibus measure of processing efficiency (speed of neural transmission, amount of neural tissue, and so on). It exists as a coherent variable only because performance scores on subtests like vocabulary, digit string memorization, and factual knowledge intercorrelate, yielding a statistical principal component, probably a global measure of neural fitness.

While I defend the existence and utility of IQ and its principal component, general intelligence or g, in the study of individual differences, I think it’s completely irrelevant to AI, AI scaling, and AI safety. It’s a measure of differences among humans within the restricted range they occupy, developed more than a century ago. It’s a statistical construct with no theoretical foundation, and it has tenuous connections to any mechanistic understanding of cognition other than as an omnibus measure of processing efficiency (speed of neural transmission, amount of neural tissue, and so on). It exists as a coherent variable only because performance scores on subtests like vocabulary, digit string memorization, and factual knowledge intercorrelate, yielding a statistical principal component, probably a global measure of neural fitness. American Stutter, 2019–2021, novelist Steve Erickson’s journal of our ongoing plague year — the everything-at-once-all-the-time mash-up of election, pandemic, and still-unresolved attempted coup — springs from a clarifying rage that not only scorns right-wing perfidy but also looks askance at liberal good intentions (and their too-often ether-brained descendants, progressive good intentions). In Erickson’s view, liberal humanism is just not up to the job of preventing America from becoming a democracy in name only. His voice in this book is simultaneously that of a soldier exhorting his fellow combatants to get off their asses and rush with him into enemy fire, and of a disillusioned man wiping the dirt off his hands as he walks away from the grave of American democracy. It is hopeful and fierce and already grieving.

American Stutter, 2019–2021, novelist Steve Erickson’s journal of our ongoing plague year — the everything-at-once-all-the-time mash-up of election, pandemic, and still-unresolved attempted coup — springs from a clarifying rage that not only scorns right-wing perfidy but also looks askance at liberal good intentions (and their too-often ether-brained descendants, progressive good intentions). In Erickson’s view, liberal humanism is just not up to the job of preventing America from becoming a democracy in name only. His voice in this book is simultaneously that of a soldier exhorting his fellow combatants to get off their asses and rush with him into enemy fire, and of a disillusioned man wiping the dirt off his hands as he walks away from the grave of American democracy. It is hopeful and fierce and already grieving.