Alexander and Conrad in BBC:

The doom-laden headlines of our times would seem to indicate there are two futures on offer.

The doom-laden headlines of our times would seem to indicate there are two futures on offer.

In one, an Orwellian authoritarianism prevails. Fearful in the face of compounding crises – climate, plagues, poverty, hunger – people accept the bargain of the “Strong Man”: their leader’s protection in return for unquestioning allegiance as “subjects”. What follows is the abdication of personal power, choice, or responsibility.

In the other, everyone is a “consumer” and self-reliance becomes an extreme sport. The richest have their boltholes in New Zealand and a ticket for Mars in hand. The rest of us strive to be like them, fending for ourselves as robots take jobs and as the competition for ever-scarcer resources intensifies. The benefits of technology, whether artificial intelligence, bio-, neuro- or agrotechnology, accrue to the wealthiest – as does all the power in society. This is a future shaped by the whims of Silicon Valley billionaires. While it sells itself on personal freedoms, the experience for most is exclusion: a top-heavy world of haves and haves-nots.

Yet despite the bandwidth and airwaves devoted to these twin dystopias, there’s another trajectory: we call it the “citizen future”.

More here.

Researchers have restored

Researchers have restored

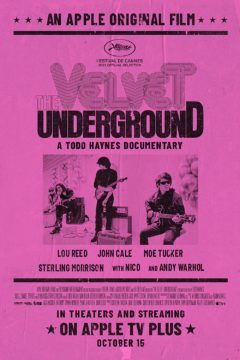

INTELLECTUAL HISTORIES OF recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “

INTELLECTUAL HISTORIES OF recent American public life typically foreground disintegration in order to capture the mood of a country on the brink. These moments are not only about the United States’s ongoing culture wars or its “ The craft of knitting is such a prominent literary act that a subgenre of literature—called “knit-lit”—has formed. Within this subgenre, there are several motifs, including what is colloquially referred to as “the sweater curse”: the idea that when someone knits a garment for their love interest, the act will seal the demise of their relationship. Knitting a garment by hand is a deeply intimate act, which perhaps explains why authors are attracted to its symbolic potential. Knitting also has an unassuming quality. The act evokes peace and domestic tranquility, and it is often employed to convey these sentiments. A knitter can become a vehicle for change, too, propelling a story forward through their handicraft. A character may weave intricate narrative webs, sometimes suggesting warmth or safety, and other times disguising the places where heartbreak, deceit, and evil may lie. If you look for them, you’ll find them—somebody in the corner, knitting a hat or a scarf, quite possibly something containing the depths of their affections or, just as probable, the names of the people they wish dead.

The craft of knitting is such a prominent literary act that a subgenre of literature—called “knit-lit”—has formed. Within this subgenre, there are several motifs, including what is colloquially referred to as “the sweater curse”: the idea that when someone knits a garment for their love interest, the act will seal the demise of their relationship. Knitting a garment by hand is a deeply intimate act, which perhaps explains why authors are attracted to its symbolic potential. Knitting also has an unassuming quality. The act evokes peace and domestic tranquility, and it is often employed to convey these sentiments. A knitter can become a vehicle for change, too, propelling a story forward through their handicraft. A character may weave intricate narrative webs, sometimes suggesting warmth or safety, and other times disguising the places where heartbreak, deceit, and evil may lie. If you look for them, you’ll find them—somebody in the corner, knitting a hat or a scarf, quite possibly something containing the depths of their affections or, just as probable, the names of the people they wish dead. Wait for tea to cool before drinking it, avoid all alcohol, crowds, reading, writing letters, wear warm clothes in the evening, eat rhubarb from time to time, have a napkin at breakfast, remember notebook.” These memoranda, as recorded in Lesley Chamberlain’s Nietzsche in Turin, capture the regime Friedrich Nietzsche followed in that city, in the last of his many lodgings during his wanderings across Europe. He loved long walks, but any interruption of routine was as toxic for him as bad food, so he avoided fashionable cafés and promenades. Even a bookshop was off-limits for fear of bumping into an acquaintance who might want to talk about Hegel. He needed, above all, a quiet life.

Wait for tea to cool before drinking it, avoid all alcohol, crowds, reading, writing letters, wear warm clothes in the evening, eat rhubarb from time to time, have a napkin at breakfast, remember notebook.” These memoranda, as recorded in Lesley Chamberlain’s Nietzsche in Turin, capture the regime Friedrich Nietzsche followed in that city, in the last of his many lodgings during his wanderings across Europe. He loved long walks, but any interruption of routine was as toxic for him as bad food, so he avoided fashionable cafés and promenades. Even a bookshop was off-limits for fear of bumping into an acquaintance who might want to talk about Hegel. He needed, above all, a quiet life. With so many lives affected by cancer — in the United States alone, about

With so many lives affected by cancer — in the United States alone, about  The ripple effects that come from the removal or diminished size of a predator’s population:

The ripple effects that come from the removal or diminished size of a predator’s population: Scene: Scandinavia, late summer, a cloudless night. The Dark Ages. Seemingly from nowhere, a quasihuman monster, descended from Cain, hears the sounds of warriors reveling in their Great Hall and decides to silence them. Creeping out of the unstructured darkness of his usual stomping grounds, this monster sneaks into the Great Hall and slaughters the warriors in their sleep. The monster develops a taste for blood, so these murders become habitual. For years.

Scene: Scandinavia, late summer, a cloudless night. The Dark Ages. Seemingly from nowhere, a quasihuman monster, descended from Cain, hears the sounds of warriors reveling in their Great Hall and decides to silence them. Creeping out of the unstructured darkness of his usual stomping grounds, this monster sneaks into the Great Hall and slaughters the warriors in their sleep. The monster develops a taste for blood, so these murders become habitual. For years. Wading into current gender debates is not for the faint of heart, but that has not discouraged Dutch-born primatologist Frans de Waal from treading where others might not wish to go. In Different, he draws on his

Wading into current gender debates is not for the faint of heart, but that has not discouraged Dutch-born primatologist Frans de Waal from treading where others might not wish to go. In Different, he draws on his  What is a paragraph? Consult a writing guide, and you will receive an answer like this: “A paragraph is a group of sentences that develops one central idea.” However solid such a definition appears on the page, it quickly melts in the heat of live instruction, as any writing teacher will tell you. Faced with the task of assembling their own paragraphs, students find nearly every word in the formula problematic. How many sentences belong in the “group?” Somewhere along the way, many were taught that five or six will do. But then out there in the world, they have seen (or heard rumors of) bulkier and slimmer specimens, some spilling over pages, some consisting of a single sentence. And how does one go about “developing” a central idea? Is there a magic number of subpoints or citations? Most problematic of all is the notion of the main “idea” itself. What qualifies? Facts? Propositions? Your ideas? Someone else’s?

What is a paragraph? Consult a writing guide, and you will receive an answer like this: “A paragraph is a group of sentences that develops one central idea.” However solid such a definition appears on the page, it quickly melts in the heat of live instruction, as any writing teacher will tell you. Faced with the task of assembling their own paragraphs, students find nearly every word in the formula problematic. How many sentences belong in the “group?” Somewhere along the way, many were taught that five or six will do. But then out there in the world, they have seen (or heard rumors of) bulkier and slimmer specimens, some spilling over pages, some consisting of a single sentence. And how does one go about “developing” a central idea? Is there a magic number of subpoints or citations? Most problematic of all is the notion of the main “idea” itself. What qualifies? Facts? Propositions? Your ideas? Someone else’s? AT THE BEGINNING OF

AT THE BEGINNING OF