Elif Batuman, Edna Bonhomme, Hazel V. Carby, Linda Colley, Meehan Crist, Anne Enright, Lorna Finlayson, Lisa Hallgarten and Jayne Kavanagh, Sophie Lewis, Maureen N. McLane, Erin Maglaque, Gazelle Mba, Azadeh Moaveni, Toril Moi, Joanne O’Leary, Niela Orr, Lauren Oyler, Susan Pedersen, Jacqueline Rose, Madeleine Schwartz, Arianne Shahvisi, Sophie Smith, Rebecca Solnit, Alice Spawls, Amia Srinivasan, Chaohua Wang, Marina Warner, Bee Wilson, Emily Witt in the LRB (image by WomenArtistUpdates – Own work):

Elif Batuman, Edna Bonhomme, Hazel V. Carby, Linda Colley, Meehan Crist, Anne Enright, Lorna Finlayson, Lisa Hallgarten and Jayne Kavanagh, Sophie Lewis, Maureen N. McLane, Erin Maglaque, Gazelle Mba, Azadeh Moaveni, Toril Moi, Joanne O’Leary, Niela Orr, Lauren Oyler, Susan Pedersen, Jacqueline Rose, Madeleine Schwartz, Arianne Shahvisi, Sophie Smith, Rebecca Solnit, Alice Spawls, Amia Srinivasan, Chaohua Wang, Marina Warner, Bee Wilson, Emily Witt in the LRB (image by WomenArtistUpdates – Own work):

Amia Srinivasan

The most famous philosophical treatment of abortion is an essay by Judith Jarvis Thomson published in 1971, two years before Roe v. Wade was decided, in the inaugural issue of the journal Philosophy and Public Affairs. ‘A Defence of Abortion’ opens by dispensing with the standard pro-choice premise that the foetus is not a person. A ‘newly implanted clump of cells’, Thomson writes, is ‘no more a person than an acorn is an oak tree’, but ‘we shall probably have to agree that the foetus has already become a human person well before birth.’ But is that what matters? Imagine, Thomson says, that you wake up to find that the Society of Music Lovers has hooked your circulatory system up to a famous violinist with a life-threatening kidney ailment. Unless you stay in bed, attached to him for nine months (you are the only one with the right blood type), he will die. Are you morally permitted to unplug the violinist?

The hospital director explains why not:

Tough luck, I agree, but you’ve now got to stay in bed, with the violinist plugged into you ... Because remember this. All persons have a right to life, and violinists are persons. Granted you have a right to decide what happens in and to your body, but a person’s right to life outweighs your right to decide what happens in and to your body.

Thomson suggests that most readers will find the doctor’s logic ‘outrageous’. Yes, the violinist is a person; but no, obviously, his right to life does not trump your right to bodily autonomy.

More here.

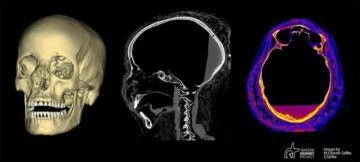

A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their

A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their  In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin

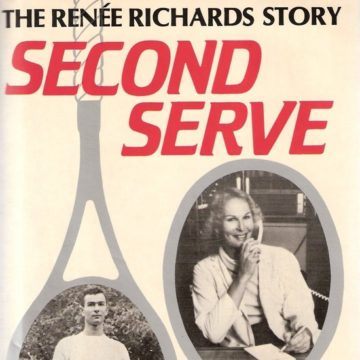

In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin  RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by

Louis Rogers in Sidecar (image by

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was

So now we can answer the question: How does democracy die? It dies not in darkness, as the Washington Post’s Trump-era slogan would have it, but in the White House itself, in the private dining room off the Oval Office, with the sound of Fox News blaring in the background. That private dining room was  We are all going to die. Most of us don’t know when. But what if we did know? What if we were told the year, the month, even the day? How would that change our lives? These questions drive Nikki Erlick’s debut novel, “The Measure,” which weighs Emerson’s claim that “it is not the length of life, but the depth of life” that matters.

We are all going to die. Most of us don’t know when. But what if we did know? What if we were told the year, the month, even the day? How would that change our lives? These questions drive Nikki Erlick’s debut novel, “The Measure,” which weighs Emerson’s claim that “it is not the length of life, but the depth of life” that matters. We have seen nothing yet. The dangerous heat England is suffering at the moment is already

We have seen nothing yet. The dangerous heat England is suffering at the moment is already  Humans have been expressing thoughts with language for tens (or perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. It’s a hallmark of our species — so much so that scientists once speculated that the capacity for language was the key difference between us and other animals. And we’ve been wondering about each other’s thoughts for as long as we could talk about them.

Humans have been expressing thoughts with language for tens (or perhaps hundreds) of thousands of years. It’s a hallmark of our species — so much so that scientists once speculated that the capacity for language was the key difference between us and other animals. And we’ve been wondering about each other’s thoughts for as long as we could talk about them. In her new book, The Bin Laden Papers, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has gone through the huge collection of information purloined by Navy Seals in their 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout, information that was declassified in 2017. The book essentially concludes that Carle had it right. Although “falsely” taken to be “a Leviathan in the jihadi landscape,” she says al-Qaeda has actually been notable mainly for its “operational impotence” while bin Laden, its fabled, if notorious, leader, continued to pursue “alarmingly sophomoric” goals and was “powerless and confined to his compound, over-seeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.”

In her new book, The Bin Laden Papers, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has gone through the huge collection of information purloined by Navy Seals in their 2011 raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout, information that was declassified in 2017. The book essentially concludes that Carle had it right. Although “falsely” taken to be “a Leviathan in the jihadi landscape,” she says al-Qaeda has actually been notable mainly for its “operational impotence” while bin Laden, its fabled, if notorious, leader, continued to pursue “alarmingly sophomoric” goals and was “powerless and confined to his compound, over-seeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.”