Month: October 2022

Economists win Nobel prize for showing why banks fail

Philip Ball in Nature:

Ben Bernanke at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, Douglas Diamond at the University of Chicago in Illinois and Philip Dybvig at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, shared equal parts of the 10-million-Swedish-krona (US$915,000) award, formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

Ben Bernanke at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, Douglas Diamond at the University of Chicago in Illinois and Philip Dybvig at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, shared equal parts of the 10-million-Swedish-krona (US$915,000) award, formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

The research of the three laureates has helped to explain both why banks exist in the form they do and why they have fragilities that can be devastating to the economy, as shown in the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the Great Depression that followed, and in the global financial crisis of 2007–09. Insights from their work were essential in enabling banks, governments and international institutions to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic without catastrophic economic consequences, the Nobel committee said in its 10 October announcement.

More here.

The medical test paradox, and redesigning Bayes’ rule

Tuesday Poem

The Earth’s Wild Places

Your eyes, your mouth, your hands,

the public highways.

Hands, like truck stops,

semis rumbling in the corners,

Eyes like the bank clerk’s window

foreign exchange.

I love all the parts of your body

friends hug your suburbs

farmlands are given a nod

but I know the path

to your wilderness.

It’s not that I like it best,

but we’re almost always

alone there,

and it’s scary but also calm.

by Gary Snyder

from This Present Moment

Counterpoint Press, Berkeley,2015

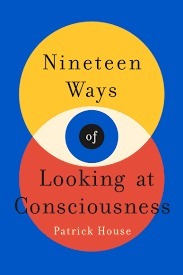

What Is It Like to Have a Brain?: “Nineteen Ways of Looking at Consciousness”

Henry Cowles in LARB:

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

It marked the edge

Of one of many circles.

BLACKBIRDS AREN’T ALL BLACK. They can be red-winged or red-shouldered, saffron-cowled or tricolored, rusty or yellow-hooded or chestnut-capped. And that’s just the members of the family Icteridae called blackbirds. Orioles and grackles, with their oranges and iridescence, are part of the family too. Old World blackbirds, many of which are called thrushes, are only distantly related; black birds like ravens and most crows aren’t blackbirds at all. To me, this fuzziness is part of the joke of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” a poem by Wallace Stevens first published in 1917. Across the poem’s 13 cantos, birds whirl and whistle, cast their shadows or eye us from the trees. Whether or not they’re all blackbirds — and, if so, what kind, with what colors? — the singular “a” of Stevens’s title is clearly misdirection. There are as many birds as there are perspectives, if not more, and as ever, what is true of the poem is true of the world. The more ways we look, the more we realize how much there is to see. Glance by glance, the blackbirds multiply.

Think about anything often enough, from enough angles, and it’s bound to splinter and refract. Our minds are like kaleidoscopes, packed with mirrors we twist to see the world anew. Sometimes we’re twisting consciously, sometimes unconsciously. But no matter what, we end up seeing patterns that are more a product of the tool in hand than of the world on its other end. Stevens’s poem, on this reading, is less about blackbirds than about the lenses we use to spy on them. It’s a warning, in other words, not to mistake the kaleidoscope for the universe.

More here.

Human Brain Cells Grow in Rats, and Feel What the Rats Feel

Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

Scientists have successfully transplanted clusters of human neurons into the brains of newborn rats, a striking feat of biological engineering that may provide more realistic models for neurological conditions such as autism and serve as a way to restore injured brains.

Scientists have successfully transplanted clusters of human neurons into the brains of newborn rats, a striking feat of biological engineering that may provide more realistic models for neurological conditions such as autism and serve as a way to restore injured brains.

In a study published on Wednesday, researchers from Stanford reported that the clumps of human cells, known as “organoids,” grew into millions of new neurons and wired themselves into their new nervous systems. Once the organoids had plugged into the brains of the rats, the animals could receive sensory signals from their whiskers and help generate command signals to guide their movements. Dr. Sergiu Pasca, the neuroscientist who led the research, said that he and his colleagues were now using the transplanted neurons to learn about the biology underlying autism, schizophrenia and other developmental disorders.

More here.

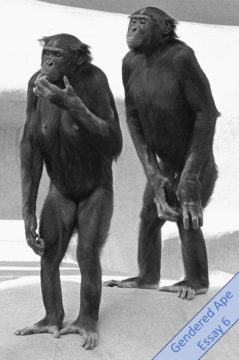

The Gendered Ape, Essay 6: Those Embarrassing Bonobos!

Editor’s Note: Frans de Waal’s new book, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist, has generated some controversy and misunderstanding. He will address these issues in a series of short essays which will be published at 3QD and can all be seen in one place here. More comments on these essays can also be seen at Frans de Waal’s Facebook page.

by Frans de Waal

It’s not always easy to talk about bonobos at academic gatherings. There is no issue with fellow primatologists, who are used to straightforward descriptions of sexual behavior and know the recent evidence. But it’s different with people outside my field, such as anthropologists, philosophers, or psychologists. They become fidgety, scratch their heads, snicker, or adopt a puzzled look. Why do bonobos stump them?

One reason for the discomfort is excessive shyness about erotic behavior, which bonobos exhibit in all positions that we can imagine, and even some that we can’t. Moreover, these apes do it in all partner combinations. People assume that animals use sex only for reproduction, but I estimate that three quarters of bonobo sex has nothing to do with it.

But there is a deeper reason why bonobos are the black sheep of our extended family despite being as close to us as chimpanzees. They fail to conform to the traditional model of the human ancestor. Most evolutionary scenarios of our species stress male bonding, male dominance, hunting, aggression, and territorial warfare. This is how our species conquered the earth, it is thought.

Chimpanzee behavior, which can be quite violent, lends support to this narrative. This ape is therefore happily embraced as model. The peaceful, female-dominated bonobo, on the other hand, doesn’t fit. The species is sidelined, such as in “The Better Angels of Our Nature,” in which Steven Pinker calls bonobos “very strange primates.” And Richard Wrangham, in “The Goodness Paradox,” portrays them as an evolutionary offshoot, who “have gone their separate way.” In other words, bonobos may be delightful apes, they are bizarre and irrelevant. Let’s just ignore them! Read more »

On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant

Review by Leanne Ogasawara

- The discovery of a book of letters written by a soldier and artist to his wife during World War I, and the recognition of this book of letters drives us into a consideration of the Great War, which was a kind of Apocalypse.

In 2011, philosopher and art critic Morgan Meis is wandering the halls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. A show on German Expressionism is on, and Meis finds himself transfixed by a certain picture. It is Franz Marc’s 1913 oil, The World Cow. The languid rust-colored creature in the painting calls to mind a cow seen in real life. Recognizing those eyes, Meis recalls its patient stare. Wasn’t there perhaps a hint of rebuke in the cow’s eyes?

This cow becomes the moment of possession. Or perhaps it was more like the first beckoning; for a year or so later Meis stumbles on a book of collected letters that the German painter wrote to his wife whilst a soldier in the Great War. It would be in the war where Franz Marc would lose his life, his skull shattered by a bullet.

Meis is hooked.

Meis’s next stop is Switzerland, where he and his dear friend Abbas Raza—to whom the book is dedicated– stand before Franz Marc’s monumental 1913 The Fate of the Animals, in the Kunstmuseum, Basel. At first glance, he thinks it is a work of early abstract art. With its strong slashes of primary colors, the immediate impression is one of violence. Looking closer, however, the animals come into focus. There is a bluish deer in the lower center, appearing in grave distress. Is the deer being sacrificed? And if so, to what purpose, he wonders. Other animals—including boars and horses—can be just made out among the shafts of color. Is this the end of the world? Read more »

Raji Cells

by Raji Jayaraman

Scheduled departure at Dulles came and went as we waited for the last passenger to board. Although the non-smoking section in the rear cabin was full, the smoking section where I sat was half empty. Death by asphyxiation on the flight to Paris was a distinct possibility but with three empty, adjacent seats in the centre nave there was some chance that my obituary might read, “She died peacefully, in recumbent sleep.”

Scheduled departure at Dulles came and went as we waited for the last passenger to board. Although the non-smoking section in the rear cabin was full, the smoking section where I sat was half empty. Death by asphyxiation on the flight to Paris was a distinct possibility but with three empty, adjacent seats in the centre nave there was some chance that my obituary might read, “She died peacefully, in recumbent sleep.”

A threat to abandon the tardy passenger filtered from the departure gate through the hull of the aircraft. Five minutes later, just as the pilot was threatening to offload his luggage, the no-show showed. Buckling under the weight of duty-free shopping bags, he made his way apologetically down the far aisle of the cabin, pausing at my row. From behind my paper, I listened to the sound of the overhead locker being opened and then clicked shut. My hopes for a good night’s rest sank with the soft thump at the far end of my four-seater.

At cruising altitude the signs blinked green, and the smokers lit up like runners at their starting blocks upon hearing the shot of the race pistol. The flight attendant rolled the drinks trolly up the aisle. I folded my paper and placed it on the empty seat beside me. As I lowered my tray table, I heard a voice at my far left ask, “Can I use your newspaper, please?” I turned to respond, but the words stuck in my throat as my eyes landed upon the most stunning man I had ever seen—the kind Michelangelo would have immortalized in white marble. He returned my stare with a disarming smile, with all the unselfconscious charm that only those born beautiful possess.

He reached out his right hand. Snatching it, I blurted my name, noticing too late that his outstretched palm had been upturned in anticipation of the paper. Retracting my hand clumsily, I retrieved the paper and handed it to him. He took it but laid it on the empty seat beside him without so much as a glance. “Thank you,” he said, “But please can you repeat: what is your name?” “Raji,” I repeated, more articulately this time. “My name is Raji.” It was his turn to be dumbstruck. Read more »

Monday Poem

Talking with my Guru

….. — Nothing and Emptiness

Me: What is emptiness?

G: What do you mean by emptiness?

Me: I mean nothing.

G: Then why are we discussing it?

…. Take your tiny Tao shears

…. and snip emptiness out of Webster’s

…. and heave it into the void. It’s another

…. self-serving tool like time

…. and collateral damage

…. Cut wood, draw water

…. and stop sound-biting life & death,

…. and travel light (and lightly)

…. until no sun remains

…. Nothing and Emptiness

…. are for advanced students

…. with nothing left to lose or gain

Jim Culleny

October 2007

Out of Indifference

by Ada Bronowski

Indifference is an attitude first theorised as a philosophical stance by ancient Greek Stoic philosophers from the 3rd century BC. It was conceived as the right attitude to cultivate in reaction to indifferent things. What was surprising were the things the Stoics considered to be indifferent and hence require us to be indifferent to. Not your usual ‘whether the number of hairs on your head is odd or pair’, or the number of billions of stars in the galaxy, or even what colour underwear your boss wears – though in some circumstances, the latter can start becoming titillating. And titillation is of course what it’s all about. It’s the tickle that spurs the Stoic to resist it. Resisting what exactly? Feeling, uncontrolled gratification, heart-melting, giving in, touching, kiss-&-make-up-ing.

Indifference is an attitude first theorised as a philosophical stance by ancient Greek Stoic philosophers from the 3rd century BC. It was conceived as the right attitude to cultivate in reaction to indifferent things. What was surprising were the things the Stoics considered to be indifferent and hence require us to be indifferent to. Not your usual ‘whether the number of hairs on your head is odd or pair’, or the number of billions of stars in the galaxy, or even what colour underwear your boss wears – though in some circumstances, the latter can start becoming titillating. And titillation is of course what it’s all about. It’s the tickle that spurs the Stoic to resist it. Resisting what exactly? Feeling, uncontrolled gratification, heart-melting, giving in, touching, kiss-&-make-up-ing.

The quintessential titillation is pleasure, sensorial or otherwise. The first Greek Stoics, pioneers of austere indifference, doubted there even really was such a thing: ‘pleasure, if it even exists’ reports of them their most stalwart chronicler, Diogenes Laertius[1]. But the more world-wise Romans, whose genius, after all, was to find pleasure in every aspect of everyday life from grooming to the delivery of justice in an orgy of spectacular blood, could not echo such a flat denial. The Roman Stoics we still know of, happen mostly to be from amongst the most prominent, wealthy and powerful figures of their time who could not but make full fruition of the gamut of pleasures life had on offer. It was the Roman Stoics who transformed the Stoic possibly non-existent pleasure into a tickle. Read more »

What We Don’t Know

by Rebecca Baumgartner

We prefer not to think about our own ignorance. We hope it sorts itself out as we get older and presumably wiser. We especially resent having it pointed out to us – which of course is very counterproductive if the goal is to get rid of it. The better approach is to cultivate an appreciation for our ignorance, get comfortable with it and look at it very closely, disentangling it as much as possible from our ego to see what’s really there (or not there).

* * *

This is the moral lesson in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, which isn’t really about Christmas, of course, despite the yuletide trappings; the emotional heart of the story is a man discarding his attachment to pride and expanding the definition of himself to make room for new knowledge about the world. In other words, it’s about the importance of learning, and the courage it takes to learn and change.

The Ghost of Christmas Present makes this explicit when he shows Scrooge two filthy urchins crouching at his feet, a boy symbolizing Ignorance and a girl symbolizing Want. The Spirit makes it clear that Ignorance is the greater threat of the two: “On his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.”

We’re very good at ignoring our ignorance. It took several supernatural interventions just for Scrooge to start to admit that his conception of the world was flawed. We might give him a hard time about this, but in reality all of us are bad about seeing what we don’t want to see. That’s why the Spirits had to be so heavy-handed – it required a series of guilt-trips bordering on psychological warfare for Scrooge (and the audience) to see the extent of the problem.

“Deny it!” the Spirit says sarcastically. “Slander those who tell it ye! Admit it for your factious purposes, and make it worse. And abide the end!” In other words, go ahead and stay in denial about your ignorance and impugn those who point it out – go on, he says, I dare you to brush this aside and see where it gets you. Read more »

Perceptions

How Many Children’s Lives Is That Worth?

by Thomas R. Wells

According to the meta-charity GiveWell, the most effective charities can save a child’s life for between 3 and 5,000 US dollars. One way of understanding this figure is that whenever you consider spending that amount of money, one of the things you would be choosing not to spend it on is saving a child’s life.

According to the meta-charity GiveWell, the most effective charities can save a child’s life for between 3 and 5,000 US dollars. One way of understanding this figure is that whenever you consider spending that amount of money, one of the things you would be choosing not to spend it on is saving a child’s life.

Take the median of the GiveWell figures: $4,000. I propose that prices for all goods and services should be listed in the universal alternative currency of percentage of a Child’s Life Not Saved (%CLNS), as well as their regular prices in Euros, dollars, or whatever. For example, a Starbucks Frappucino might be priced at 5$ /0.13%CLNS. A Caribbean holiday cruise might be priced at $8,000/ 200%CLNS.

The justification for this would be to fix a gap in the way the price system functions. Normally we make our consumption decisions entirely in terms of a consideration of how much we want something and how much we can afford, a matter of prudence only. As economists have analysed, such exercises in constrained maximisation are all we need do to enjoy a flourishing economy since by responding to prices we automatically take into account the social cost to others of resources being used for what we want rather than for something else (so long as some wise and non-self-interested government steps in to correct for externalities).

Occasionally it is questioned whether merely responding rationally to the information revealed by prices is enough. For example, perhaps we should also be pushed to take account of the impact of our choices on non-human entities by explicit ethical warnings on animal products (previously). Read more »

Cruising, or: A Map to the Next World, or: A Map to the World Past

by Michael Abraham

It was in the midst of thinking about my own childhood and friendships, of thinking about faith and magic and the End of the World and the World to Come, in the midst of reflecting quite deeply on these things, which for me are so profoundly interwoven, so profoundly interwoven because, in the tapestry they make together, there is, glimmering, the idea of what love is and means, the sense I have of amory, of life’s affectionate trajectory and the purpose of affection in the trajectory of life—it was in the midst of reflecting on these these things and of writing about them over and over that I met a man we’ll call Khalid.

I was in Tribeca, playing pool with the friend I once liked to call Shakti in my writing. She had to run off to a dinner, and so I was left on my own with a beautiful summer night thrumming around me. O, it was perfect. It was deep purple and eighty degrees with a strange chill in the breeze—everything New York in August is supposed to be. I was two blocks from the train to my house, but how could I go home on such a night? So, I decided I would walk north from Tribeca to the Christopher Street pier. This pier is a mightily historical place, both for me personally and for queer history itself. It was on this and the surrounding piers that voguing was invented by unhoused Black and Brown queer youth in between turning tricks, as they dance battled to pass the night. It was on this and the surrounding piers that so much of the twentieth century gay and trans lifeworld of sex and friendship existed. It was also on this pier that I first discovered myself as a queer man. I had been gay long before the discovery of course; I came out at fourteen. But I was not queer until I was nineteen. I was taking a class my second semester of freshman year at NYU, taught by Tamuira Reid, in the writing of creative nonfiction and immersive journalism. For our final projects, we had to pick something to immersively research, something to involve ourselves in, and then write a long-form lyrical essay about it. Having recently been exposed to Elegance Bratton’s then-unreleased film, Pier Kids, which follows the lives of three unhoused queer youth as they secure housing, I decided what I would write about were just these people, the unhoused youth of color who make the Christopher Street pier their nightly home. Looking back, I can see how voyeuristic and naïve this was. But I didn’t want to meet the pier kids to gawk at them. I had a sense, a sense merely, that they knew something, many things, about the kind of people we are, them and me, that I did not yet know. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

In Science, “the Fate of What We Say and Make is in Later Users’ Hands”

by Joseph Shieber

1. There’s something ironic about the fact that the received wisdom about science is that science teaches us not to trust received wisdom. Or, to paraphrase a recent blog post that seems oblivious to this irony: “Scientific expert opines, ‘Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts.’”

I should be fair to Daniel Lemire, the author of that blog post. He does a good job of spelling out the received wisdom about science, as well as of reflecting the orthodox opinion about the scientific expert that Lemire takes as his authority, the Nobel prizewinning physicist, lock-picker, and bongo-player, Richard Feynman.

Unfortunately, Lemire is wrong on both points: the received wisdom about science is hopelessly naive and, far from being a univocal opponent of the importance of expert opinion, Feynman was himself rather confused about the role of iconoclasm in science.

2. Let me begin by tackling the second, in some sense less interesting, point concerning Feynman interpretation.

Far from being of the opinion that all scientists should be iconoclasts who question the experts, the bulk of Feynman’s writing is far more nuanced than the pull-quotes that are turned into the posters that adorn undergraduate science majors’ dorm rooms.

Before appealing to Feynman as an authority on the nature of science, it is worthwhile to keep in mind that Feynman’s field of expertise isn’t the nature of science itself, but theoretical physics. This is important, since, as Feynman himself noted, “In order to talk about the impact of ideas in one field on ideas in another field one is always apt to be an idiot of one kind or another. In these days of specialization, there are few people who have such a deep knowledge of two departments of our understanding that they don’t make fools of themselves in one or the other.” (“The Uncertainty of Science,” John Danz Lecture Series, 1963)

With that in mind, we can appreciate the ways in which slogans like, “science is the belief in the ignorance of experts,” do an injustice to Feynman’s own insights about the nature of science. I’ll briefly sketch five ways in which this is true. Read more »

Bell’s Theorem: A Nobel Prize For Metaphysics

by Jochen Szangolies

There has been no shortage of articles on this year’s physics Nobel, which, just in case you’ve been living under a rock, was awarded to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science”. Why, then, add more to the pile?

A justification is given be John Bell himself in his 1966 review article On the Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics: “[l]ike all authors of noncommissioned reviews [the writer] thinks that he can restate the position with such clarity and simplicity that all previous discussions will be eclipsed”. While I like to think that I’m generally more modest in my ambitions than Bell semi-seriously positions himself here, I feel that there is a lacuna in most of the recent coverage that ought to be addressed. That omission is that while there is much talk about what the prize-winning research implies—from the possibility of groundbreaking new quantum technologies to the refutation of dearly held assumptions about physical reality—there is considerably less talk about what it, and Bell’s theorem specifically, actually is, and why it has had enough impact beyond the scientific world to warrant the unique (to the best of my knowledge) distinction of having a street named after it.

In part, this is certainly owed to the constraints of writing for an audience with a diverse background, and the fear of alienating one’s readers by delving too deeply into what might seem like overly technical matters. Luckily (or not), I have no such scruples. However, I—perhaps foolishly—believe that there is a way to get the essential content of Bell’s theorem across without breaking out its full machinery. Indeed, the bare statement of his result is quite simple. At its core, what Bell did was to derive an inequality—a bound on the magnitude of a certain quantity—such that, when it holds, we can write down a joint probability distribution for the possible values of the inputs of the inequality, where these ‘inputs’ are given by measurement results.

Now let’s unpack what this means. Read more »

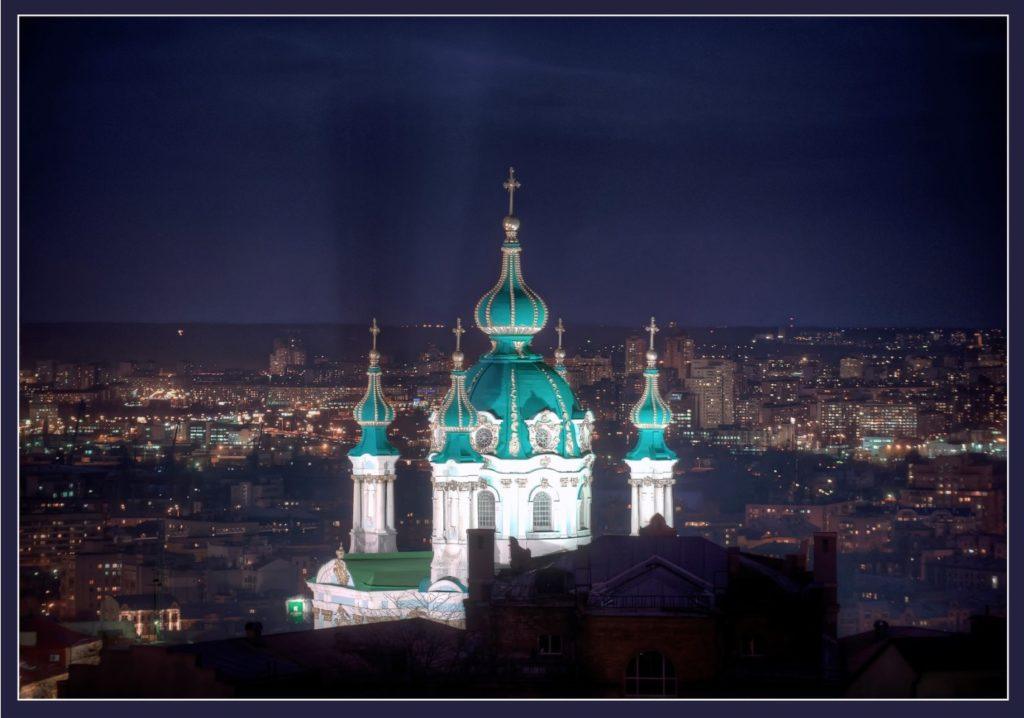

Monday Photo

On the Road: Back Home

by Bill Murray

In spring the pandemic lurked. Boris Johnson was Ukraine’s new best friend, Russia’s domination of Ukraine appeared imminent and the UK basked in the queen’s platinum jubilee. I’ve been away since spring. Have I missed anything?

The war continues. Many who caution they can’t get inside Vladimir Putin’s head proclaim from in there that his scheme is to split and outlast a freezing western alliance this winter. We operate from that premise this fall, while minding an added pinch of Kremlin nuclear horseplay.

Putin must now fulminate over his mobilization. Timothy Snyder thinks this war was meant to be played out as a Russian TV event “about a faraway place.” But as the birches fade in Moscow, the fight creeps ever farther into the Motherland.

A month ago I was convinced mobilization wasn’t in the cards, because by the time call-ups got even the most basic training it would be that muddy time of year when the weather constrains fighting vehicles to the roads and the great European plain becomes a great big mess.

So to hell with basic training.

Novaya Gazeta Europe, now operating from Riga, reports that a “hidden article of Russia’s mobilisation order allows the Defence Ministry to draft up to one million reservists into the army,” which may or may not be Putin’s intent. But finer legal points have a distinctly irrelevant feel now, as Commander Putin appears to be personally running the war these days. Read more »

Deborah Roberts. Shankia and Grace. 2021.

Deborah Roberts. Shankia and Grace. 2021.