by Derek Neal

There are certain words that seem to take on a life of their own, words that spread imperceptibly, like a virus, replicating below the level of consciousness, latent in our environment and culture, until suddenly the word is everywhere, and we are afflicted with it. We may even use these words ourselves: we struggle to find the right phrase, the true word to capture our intention, and these words come to us unbidden, floating into our minds from somewhere out there, and we speak the word without understanding what we really mean, but we see understanding and acknowledgement in the face of our interlocutor, and we know we have hit upon the correct utterance that will mark us as one who belongs.

There are certain words that seem to take on a life of their own, words that spread imperceptibly, like a virus, replicating below the level of consciousness, latent in our environment and culture, until suddenly the word is everywhere, and we are afflicted with it. We may even use these words ourselves: we struggle to find the right phrase, the true word to capture our intention, and these words come to us unbidden, floating into our minds from somewhere out there, and we speak the word without understanding what we really mean, but we see understanding and acknowledgement in the face of our interlocutor, and we know we have hit upon the correct utterance that will mark us as one who belongs.

Journey

Here are some uses of the word “journey” that I’ve heard or read recently: faith journey, personal development journey, teeth journey, skincare journey, healing journey, leadership journey, finance journey, mental health journey, breast cancer journey, fertility journey, musical journey, immigration journey, medical journey, weight loss journey, pregnancy journey. The first thing we notice about these “journeys” is their combination with another word, increasingly a noun. It seems to me that the use of journey used to be exclusively about physical travel from one place to another (journey to the stars, journey to the center of the earth), or that an adjective would be used to describe a journey (harrowing journey, difficult journey), but now nouns are often used to describe a type of journey, which enables us to turn any sort of experience into a narrative story. Just now, when attempting to pay my credit card bill, I was told that my bank could help me on my “credit journey.” The word “journey” acts like a spell—once it is cast, it performs a sort of magic, turning something without order or structure into something that we can trust will turn out well, because it’s about the journey, not the destination. Read more »

In the US, we are feeling the sickening after-effects of

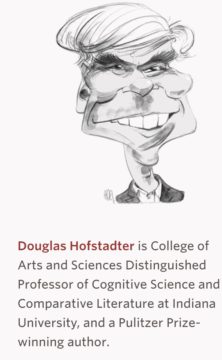

In the US, we are feeling the sickening after-effects of  Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language.

Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language. In 1977, Ken Olsen declared that ‘there is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.’ In 1995, Robert Metcalfe predicted in InfoWorld that the internet would go ‘spectacularly supernova’ and then collapse within a year. In 2000, the Daily Mail reported that the ‘Internet may be just a passing fad,’ adding that ‘predictions that the Internet would revolutionise the way society works have proved wildly inaccurate.’ Any day now, the millions of internet users would simply stop, either bored or frustrated, and rejoin the real world.

In 1977, Ken Olsen declared that ‘there is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.’ In 1995, Robert Metcalfe predicted in InfoWorld that the internet would go ‘spectacularly supernova’ and then collapse within a year. In 2000, the Daily Mail reported that the ‘Internet may be just a passing fad,’ adding that ‘predictions that the Internet would revolutionise the way society works have proved wildly inaccurate.’ Any day now, the millions of internet users would simply stop, either bored or frustrated, and rejoin the real world. Nobel Prizes used to be awarded fairly quickly after the discovery, achievement, or event that prompted them. The instructions left by Alfred Nobel seemed to warrant this speed. However, this has occasionally led to awards for discoveries that later turned out to be bunk. Perhaps no case of this is clearer-cut than the 1926 prize in medicine, which was awarded “for [Fibiger’s] discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma.”

Nobel Prizes used to be awarded fairly quickly after the discovery, achievement, or event that prompted them. The instructions left by Alfred Nobel seemed to warrant this speed. However, this has occasionally led to awards for discoveries that later turned out to be bunk. Perhaps no case of this is clearer-cut than the 1926 prize in medicine, which was awarded “for [Fibiger’s] discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma.” The House committee tasked with investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol made its closing arguments to the American public today and voted 9-0 to subpoena former President Donald Trump. They highlighted snippets from more than a million Secret Service communications in the days and hours leading up to the breach of the Capitol, bolstering their thesis that then-President Donald Trump had incited a mob and bears singular responsibility for the violence that ensued. “Armed and Ready, Mr. President!” read one snippet of intelligence presented in a Secret Service email on Dec. 24, 2020, about two weeks before the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress to formalize Joe Biden’s election victory.

The House committee tasked with investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol made its closing arguments to the American public today and voted 9-0 to subpoena former President Donald Trump. They highlighted snippets from more than a million Secret Service communications in the days and hours leading up to the breach of the Capitol, bolstering their thesis that then-President Donald Trump had incited a mob and bears singular responsibility for the violence that ensued. “Armed and Ready, Mr. President!” read one snippet of intelligence presented in a Secret Service email on Dec. 24, 2020, about two weeks before the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress to formalize Joe Biden’s election victory. Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if

Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if  Cihan Tugal in Sidecar:

Cihan Tugal in Sidecar: Samir Sonti and JW Mason in Phenomenal World:

Samir Sonti and JW Mason in Phenomenal World: Ingrid Robeyns in Crooked Timber:

Ingrid Robeyns in Crooked Timber: This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything.

This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything. In June 1794,

In June 1794,  Analytic philosophers avoided the subject of meaning in life till relatively recently. The standard explanation is that they associated it with the meaning of life question they considered bankrupt. But it’s surely also because the subject conflicts with some of the core tendencies of the analytic tradition. “What gives point to life?” is a sweeping question that invites the synoptic approach associated with continental philosophy, not the divide-and-conquer method favored by Anglo-Americans. The question also wears its angst on its sleeve, making it an awkward fit with the dispassionate mode employed in the mainstream academy.

Analytic philosophers avoided the subject of meaning in life till relatively recently. The standard explanation is that they associated it with the meaning of life question they considered bankrupt. But it’s surely also because the subject conflicts with some of the core tendencies of the analytic tradition. “What gives point to life?” is a sweeping question that invites the synoptic approach associated with continental philosophy, not the divide-and-conquer method favored by Anglo-Americans. The question also wears its angst on its sleeve, making it an awkward fit with the dispassionate mode employed in the mainstream academy.