Sara Reardon in Nature:

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity.

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity.

These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test how drugs perform against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. But one experiment has drawn more scrutiny than the others. In August 2019, Muotri’s group published a paper in Cell Stem Cell reporting the creation of human brain organoids that produced coordinated waves of activity, resembling those seen in premature babies1. The waves continued for months before the team shut the experiment down.

This type of brain-wide, coordinated electrical activity is one of the properties of a conscious brain. The team’s finding led ethicists and scientists to raise a host of moral and philosophical questions about whether organoids should be allowed to reach this level of advanced development, whether ‘conscious’ organoids might be entitled to special treatment and rights not afforded to other clumps of cells and the possibility that consciousness could be created from scratch.

More here.

In November of 1660, at Gresham College in London, an invisible college of learned men held their first meeting after 20 years of informal collaboration. They chose their coat of arms: the royal crown’s three lions of England set against a white backdrop. Their motto: “Nullius in verba,” or “take no one’s word for it.” Three years later, they received a charter from King Charles II and became what was and remains the world’s preeminent scientific institution: the Royal Society.

In November of 1660, at Gresham College in London, an invisible college of learned men held their first meeting after 20 years of informal collaboration. They chose their coat of arms: the royal crown’s three lions of England set against a white backdrop. Their motto: “Nullius in verba,” or “take no one’s word for it.” Three years later, they received a charter from King Charles II and became what was and remains the world’s preeminent scientific institution: the Royal Society. Researchers who grew a brain cell culture in a lab claim that they taught the cells to play a version of

Researchers who grew a brain cell culture in a lab claim that they taught the cells to play a version of  The energy crisis incited by Russia’s war in Ukraine has triggered intense debates in many countries about whether the windfall profits that energy companies are now making should be taxed. While this question concerns all companies that produce coal, gas, or oil, the focus currently is on electricity producers. Since a high gas price is driving up electricity prices across the board, suppliers with power plants that use other fuels or renewables can reap extremely high profits. And the immense burden of rising electricity prices on consumers has ratcheted up political pressure to tax “unjustified” profits.

The energy crisis incited by Russia’s war in Ukraine has triggered intense debates in many countries about whether the windfall profits that energy companies are now making should be taxed. While this question concerns all companies that produce coal, gas, or oil, the focus currently is on electricity producers. Since a high gas price is driving up electricity prices across the board, suppliers with power plants that use other fuels or renewables can reap extremely high profits. And the immense burden of rising electricity prices on consumers has ratcheted up political pressure to tax “unjustified” profits. WOLFGANG TILLMANS HAS CREATED an image of contemporary Europe that a lot of people carry around in their heads. Not the Colosseum or the Arc de Triomphe or even the Eiffel Tower, but easyJet, English, Berghain. These keywords are both the technologies and the coordinates of Tillmans’s practice, the atmosphere and infrastructure that support his work, though they are not necessarily visible in his pictures. And yet he has created images—indeed, icons—that are somehow correlates for them, that use these things as scaffolding. I know this is a big claim to make about an artist, given that the profession today no longer has much to do with the way things look. The task of imaging has largely been left to the stylist, the executive, and the influencer. But by leveraging photography’s many lives (as art, as document, as fashion editorial, as reportage, and as publicity), Tillmans has been able to thread the needle through an increasingly vast network of image production, and its sites of display, in order to create a new kind of image—a moving image not simply in the affective sense, but in the circulatory one, too. His images get around, change shape. They are promiscuous. We can call them images in motion.

WOLFGANG TILLMANS HAS CREATED an image of contemporary Europe that a lot of people carry around in their heads. Not the Colosseum or the Arc de Triomphe or even the Eiffel Tower, but easyJet, English, Berghain. These keywords are both the technologies and the coordinates of Tillmans’s practice, the atmosphere and infrastructure that support his work, though they are not necessarily visible in his pictures. And yet he has created images—indeed, icons—that are somehow correlates for them, that use these things as scaffolding. I know this is a big claim to make about an artist, given that the profession today no longer has much to do with the way things look. The task of imaging has largely been left to the stylist, the executive, and the influencer. But by leveraging photography’s many lives (as art, as document, as fashion editorial, as reportage, and as publicity), Tillmans has been able to thread the needle through an increasingly vast network of image production, and its sites of display, in order to create a new kind of image—a moving image not simply in the affective sense, but in the circulatory one, too. His images get around, change shape. They are promiscuous. We can call them images in motion. ONE MAN ALONE

ONE MAN ALONE “You know you’re a nerd when you store DNA in your fridge.”

“You know you’re a nerd when you store DNA in your fridge.” T

T In 2015, The New York Times Book Review posed the question “Whatever happened to the Novel of Ideas?” to the writers Pankaj Mishra and Benjamin Moser. On the question of “whether philosophical novels have gone the way of the dodo bird,” Mishra answered in the affirmative and—not a writer who shies away from generalizations—charged that the culprit was the MFA program. “America’s postwar creative-writing industry,” Mishra claimed, has “hindered literature from its customary reckoning with the acute problems of the modern epoch” and “boosted instead a cult of private experience.”

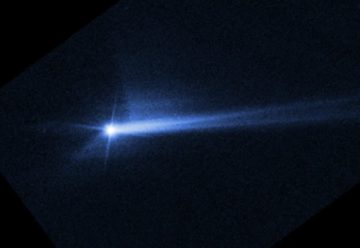

In 2015, The New York Times Book Review posed the question “Whatever happened to the Novel of Ideas?” to the writers Pankaj Mishra and Benjamin Moser. On the question of “whether philosophical novels have gone the way of the dodo bird,” Mishra answered in the affirmative and—not a writer who shies away from generalizations—charged that the culprit was the MFA program. “America’s postwar creative-writing industry,” Mishra claimed, has “hindered literature from its customary reckoning with the acute problems of the modern epoch” and “boosted instead a cult of private experience.” Humans have for the first time proved that they can change the path of a massive rock hurtling through space. NASA has announced that the spacecraft it slammed into an asteroid on 26 September succeeded in altering the space rock’s orbit around another asteroid — with better-than-expected results.

Humans have for the first time proved that they can change the path of a massive rock hurtling through space. NASA has announced that the spacecraft it slammed into an asteroid on 26 September succeeded in altering the space rock’s orbit around another asteroid — with better-than-expected results. A new paper,

A new paper,  As I write this I suddenly realize that All Souls’ Day, November 1, might have been a more timely date for the publication of this article, but alas, that is one of the (very few) inconveniences of not being a religious man. Life is life, however, and certain truths do not always dawn on us in a timely fashion; they come when they come. And in the end, there is so much more to be pondered in November, the month that Herman Melville always associated with melancholy, as he so succinctly expressed it at the beginning of Moby-Dick, through the voice of Ishmael, his narrator who said that “whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul… I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can,” since the sea was his “substitute for pistol and ball.”

As I write this I suddenly realize that All Souls’ Day, November 1, might have been a more timely date for the publication of this article, but alas, that is one of the (very few) inconveniences of not being a religious man. Life is life, however, and certain truths do not always dawn on us in a timely fashion; they come when they come. And in the end, there is so much more to be pondered in November, the month that Herman Melville always associated with melancholy, as he so succinctly expressed it at the beginning of Moby-Dick, through the voice of Ishmael, his narrator who said that “whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul… I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can,” since the sea was his “substitute for pistol and ball.” Filmmaking thrives in plenty of other cities in India, but “Bollywood” has become shorthand for Indian cinema as a whole, and for the thousand or so movies that the country releases annually. For nearly a century, Bollywood has also worn the warm, self-satisfied gloss of being a passion that unifies a country of divisions. Not only are its audiences as mixed as India itself, filmmakers will say, but Bollywood is a place where caste and religion don’t matter. The most piously presented proof of this is the fact that, in a Hindu-majority country, a Muslim man named Shah Rukh Khan has been the supreme box-office star for decades.

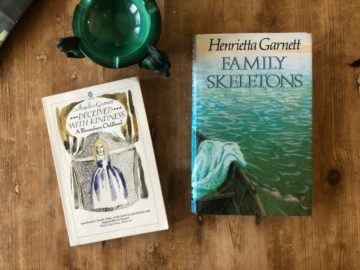

Filmmaking thrives in plenty of other cities in India, but “Bollywood” has become shorthand for Indian cinema as a whole, and for the thousand or so movies that the country releases annually. For nearly a century, Bollywood has also worn the warm, self-satisfied gloss of being a passion that unifies a country of divisions. Not only are its audiences as mixed as India itself, filmmakers will say, but Bollywood is a place where caste and religion don’t matter. The most piously presented proof of this is the fact that, in a Hindu-majority country, a Muslim man named Shah Rukh Khan has been the supreme box-office star for decades. Henrietta Garnett was forty-one when her first and last novel, Family Skeletons, was published in 1986. She knew that her debut, a tragic gothic romance revolving around a complex constellation of family secrets, would face an unusual degree of public scrutiny: Henrietta was English literary royalty, the direct descendant of the Bloomsbury Group on both sides of her family tree. Her father was the novelist David “Bunny” Garnett, author of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize–winning Lady into Fox (1922), a book so highly regarded it was on the British high school syllabus when his daughter was a teenager in the late fifties and early sixties. Henrietta’s mother was Angelica Garnett, née Bell, daughter of Virginia Woolf’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. “I had been putting off trying to get anything published,” Henrietta confessed when an interviewer asked about her famous relations, “because I couldn’t help thinking that whatever I did it would never be as good as anything they’ve achieved.” Family Skeletons is a strange and singular creation: melodramatic in plot but elegant in tone, written in a cool and fluent prose that is utterly Henrietta’s own. The novel bears no resemblance to either Bunny’s or Woolf’s fiction; nevertheless, the story does contain more psychological traces of her family’s legacy—namely, of the uniquely disturbing personal dramas that shaped the lives of those who raised her and the public perception of the Bloomsbury Group.

Henrietta Garnett was forty-one when her first and last novel, Family Skeletons, was published in 1986. She knew that her debut, a tragic gothic romance revolving around a complex constellation of family secrets, would face an unusual degree of public scrutiny: Henrietta was English literary royalty, the direct descendant of the Bloomsbury Group on both sides of her family tree. Her father was the novelist David “Bunny” Garnett, author of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize–winning Lady into Fox (1922), a book so highly regarded it was on the British high school syllabus when his daughter was a teenager in the late fifties and early sixties. Henrietta’s mother was Angelica Garnett, née Bell, daughter of Virginia Woolf’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. “I had been putting off trying to get anything published,” Henrietta confessed when an interviewer asked about her famous relations, “because I couldn’t help thinking that whatever I did it would never be as good as anything they’ve achieved.” Family Skeletons is a strange and singular creation: melodramatic in plot but elegant in tone, written in a cool and fluent prose that is utterly Henrietta’s own. The novel bears no resemblance to either Bunny’s or Woolf’s fiction; nevertheless, the story does contain more psychological traces of her family’s legacy—namely, of the uniquely disturbing personal dramas that shaped the lives of those who raised her and the public perception of the Bloomsbury Group.