Month: October 2022

When the Push Button Was New, People Were Freaked

Matthew Wills at JSTOR Daily:

The doorbell. The intercom. The elevator. Once upon a time, beginning in the late nineteenth century, pushing the button that activated such devices was a strange new experience. The electric push button, the now mundane-seeming interface between human and machine, was originally a spark for wonder, anxiety, and social transformation.

As media studies scholar Rachel Plotnick details, people worried that the electric push button would make human skills atrophy. They wondered if such devices would seal off the wonders of technology into a black box: “effortless, opaque, and therefore unquestioned by consumers.” Today, you’d probably have to schedule an electrician to fix what some children back then knew how to make: electric bells, buttons, and buzzers.

more here.

The Meaning Of Classicism

Amit Chaudhuri at n+1:

OVER A DECADE AGO, I began to inadvertently call my mother’s singing “classicist.” I say “inadvertently” because I think I was, without fully realizing it, using the word in Eliot’s sense. My mother, Bijoya Chaudhuri, was a singer of Tagore songs—largely ignored, but admired by a few for being one of the great singers of her generation. In using “classicist,” I may have meant to connect her style to North Indian classical music. And North Indian classical music is “classicist” in the way Eliot, I believe, uses the word: vocal music in this tradition preoccupies itself with the expression of the note, of the raga, but not with emotion in the conventional humanist sense—that is, not with self-expression. One of the ways it does this is by eschewing vibrato and tremolo, which became such an effective means of bringing emotional drama to opera in the Romantic period. However intricate the embellishments in North Indian classical vocal music (and they are the most complex and difficult in any vocal tradition), they must return repeatedly to the stillness (thheherao) and purity of the note. One of the ways this happens is through the ah sound that dominates North Indian classical vocal music.

OVER A DECADE AGO, I began to inadvertently call my mother’s singing “classicist.” I say “inadvertently” because I think I was, without fully realizing it, using the word in Eliot’s sense. My mother, Bijoya Chaudhuri, was a singer of Tagore songs—largely ignored, but admired by a few for being one of the great singers of her generation. In using “classicist,” I may have meant to connect her style to North Indian classical music. And North Indian classical music is “classicist” in the way Eliot, I believe, uses the word: vocal music in this tradition preoccupies itself with the expression of the note, of the raga, but not with emotion in the conventional humanist sense—that is, not with self-expression. One of the ways it does this is by eschewing vibrato and tremolo, which became such an effective means of bringing emotional drama to opera in the Romantic period. However intricate the embellishments in North Indian classical vocal music (and they are the most complex and difficult in any vocal tradition), they must return repeatedly to the stillness (thheherao) and purity of the note. One of the ways this happens is through the ah sound that dominates North Indian classical vocal music.

more here.

Thursday Poem

The Such Thing As the Ridiculous Question –

Where are you from???

When I say ancestors, let’s be clear:

I mean slaves. I’m talkin’ Tennessee

cotton & Louisiana suga. I mean grave

dirt. I come from homes & marriages

named after the same type of weapon –

all it takes is a shotgun to know

I’m Black. I don’t got no secrets

a bullet ain’t told. Danger see me

& sit down somewhere.

I’m a direct descendant of last words

& first punches. I got stolen blood.

My complexion is America’s

darkest hour. You can trace my great

great great great great grandmother back

to a scream. I bet somewhere it’s a haint

with my eyes. My last name is a protest;

a brick through a window in a house

my bones built. One million

scabs from one scar.

Heavy is the hand that held

the whip. Black is the back that carried this

country & when this country’s palm gets

an itch, I become money. You give this country

an inch & it will take a freedom. You can’t talk slick

to this legacy of oiled scalps. You can’t spit

on my race & call it reign. I sound like my mama now,

who sound like her mama who sound like her mama who

sound like her mama, who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama, who sound like a scream.

& that’s why I’m so loud, remember? You wanna know

where I’m from? Easy. Open a wound

& watch it heal.

by Siaara Freeman

from Split This Rock

Listen to reading: here

Perfectionists: Lowering your standards can improve your mental health

Tracy Dennis-Tiwary in The Washington Post:

The standards to which perfectionists hold themselves are unrealistic, overly demanding and often impossible to achieve. And when perfectionists fail to achieve perfection? We beat ourselves up with harsh self-criticism and are less able to bounce back and learn from mistakes. We’re also unlikely to celebrate our achievements or take pride in improving on our personal best. To a perfectionist, it’s all or nothing — you can be a winner or you can be an abject, worthless failure, with nothing in between.

More here.

Racism: Overcoming science’s toxic legacy

The Editorial Board at Nature:

Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses”. So wrote the guest editors of this special issue of Nature, Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam and Elizabeth Wathuti, in a June 2022 editorial announcing their involvement. Among those worst excesses is racism. For centuries, science has built a legacy of excluding people of colour and those from other historically marginalized groups from the scientific enterprise. Institutions and scientists have used research to underpin discriminatory thinking, and have prioritized research outputs that ignore and further disadvantage marginalized people.

Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses”. So wrote the guest editors of this special issue of Nature, Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam and Elizabeth Wathuti, in a June 2022 editorial announcing their involvement. Among those worst excesses is racism. For centuries, science has built a legacy of excluding people of colour and those from other historically marginalized groups from the scientific enterprise. Institutions and scientists have used research to underpin discriminatory thinking, and have prioritized research outputs that ignore and further disadvantage marginalized people.

In the minds of many who do not experience it day to day, racism consists of egregious acts of violence or abuse. But that is only part of what many people experience in science. It is also, in the words of Black geoscientist Martha Gilmore, a “persistent current in everyday interactions” — of belittlement, of denial of opportunity, of feeling that you do not belong.

More here.

Muddy Waters – Live In Chicago 1979

The Secret Life Of Leftovers

Nat Watkins at The New Atlantis:

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

This is possible because I live in a country where 30 to 40 percent of food produced is never eaten, where the average family throws out $1,500 worth of food every year, and where a typical restaurant discards about a half-pound of food per meal.

This is an astonishing historical anomaly. In almost any other time and place in human history, someone would look at the very same waste and say, “Looks delicious!”

more here.

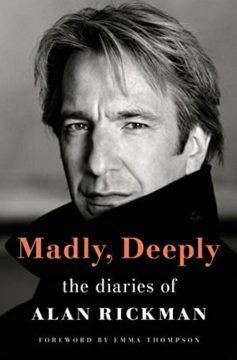

Madly, Deeply: The Alan Rickman Diaries

Thomas W Hodgkinson at Literary Review:

For anyone with a sneaker for the man and his work, these diaries are a delight. For one thing, they’re filled with his acerbic verdicts on the films and plays he sees. Vicky Cristina Barcelona he dismisses as ‘Woman’s Weekly tosh’, which seems about right. He’s no fan of the over-praised Last Seduction, noting that ‘an espresso is more rewarding’. As for Marvin’s Room, he complains it’s ‘another of those American plays which insist that you feel something’, before adding wryly, ‘I don’t think anger & frustration is what they had in mind.’

For anyone with a sneaker for the man and his work, these diaries are a delight. For one thing, they’re filled with his acerbic verdicts on the films and plays he sees. Vicky Cristina Barcelona he dismisses as ‘Woman’s Weekly tosh’, which seems about right. He’s no fan of the over-praised Last Seduction, noting that ‘an espresso is more rewarding’. As for Marvin’s Room, he complains it’s ‘another of those American plays which insist that you feel something’, before adding wryly, ‘I don’t think anger & frustration is what they had in mind.’

There are also two or three terrific anecdotes involving the glittering cast list of his friends and acquaintances. I loved Rupert Everett’s dry reply to Ruby Wax’s question about how his career is going: ‘Endlessly clawing my way back to the middle.’ Better still is Rickman’s own riposte when John Major approaches him in the stands at the 2011 Wimbledon men’s final. ‘You have given us so much enjoyment,’ gushes the former Tory prime minister. To which Rickman, a lifelong Labour supporter, cannot resist replying, ‘I wish I could say the same of you.’

more here.

Robert Pinsky on His Many Readings of Robert Lowell

Robert Pinsky in Literary Hub:

Life Studies is Robert Lowell’s best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowell’s book, “Yeah, I had a grandfather, too.” Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish”—the poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village.

Life Studies is Robert Lowell’s best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowell’s book, “Yeah, I had a grandfather, too.” Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish”—the poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village.

A year later, when I arrived as a graduate student at Stanford, I entered a culture more bucolic than what I had known at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey—the home state of Ginsberg, with urban New Brunswick about an hour from those Village streets. Surrounding the sleepy Palo Alto of those days, an actual village, the future Silicon Valley was still a place of horse ranches and apricot orchards. Leland and Jane Stanford had founded the university on their ranch, in 1891, and the school’s affectionate nickname for itself was “the Farm.” In Palo Alto, too, as in the quite different literary and urban terrain of Rutgers, Robert Lowell’s poetry was not held in the first rank of importance.

But five or six years later, in 1970, I took a job teaching at Wellesley College, not far from Boston and Cambridge, where I met poets who considered Life Studies a major work of art.

More here.

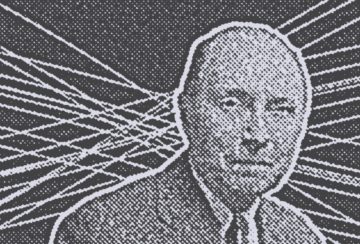

Reflections on an Essay by Eugene Wigner

Sergiu Klainerman in Inference Review:

IN THE SPRING of 1960, Eugene Wigner delivered a lecture at New York University. Published as an essay the following year under the title “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences,”1 Wigner’s remarks sparked a debate that continues to the present day. Indeed, the significance and implications of the essay have been discussed far beyond the realms of mathematics and physics.

IN THE SPRING of 1960, Eugene Wigner delivered a lecture at New York University. Published as an essay the following year under the title “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences,”1 Wigner’s remarks sparked a debate that continues to the present day. Indeed, the significance and implications of the essay have been discussed far beyond the realms of mathematics and physics.

Wigner’s essay has long been a source of fascination for me. I was a graduate student when I first read the essay and I have returned to it many times over the intervening years. Although I have often found myself admiring the clarity and articulation of Wigner’s observations, it is the mystery he pointed to that first caught my imagination and is at the heart of its enduring appeal.

The mystery Wigner described can be stated as follows: mathematical concepts introduced for solving specific problems turn out to have unexpected and mysterious consequences in seemingly unrelated areas.

More here.

Hyperthymia, rationality, and emotional self-regulation

Andrew Van Wagner interviews Ronald de Sousa, a philosopher best known for his work in philosophy of emotion, in his Substack newsletter:

1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on? And the most exciting projects that you know of that others are working on?

1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on? And the most exciting projects that you know of that others are working on?

I’m working on a project about how language affects our emotions. For this project, I’m basing my general perspective on the “dual processing” hypothesis—that there are two systems, one intuitive and one analytic—that was popularized in Daniel Kahneman’s very famous and wonderful 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow. I’m interested in how this dual system affects our emotions, which then translates into the question of how our emotions are elaborated when we talk about them—someone who values rationality might think that the analytic system should be trusted over the intuitive one, but our brains can only do a very limited amount of conscious reasoning, which means that you essentially have to rely on the intuitive system for the most part.

I’m also writing a book—Why It’s Okay to Be Amoral—that’s based on a 2021 article that I wrote about morality. I argue in the book that philosophers are basically wasting their time in trying to justify the principles that they peddle as fundamental moral principles—my view is that such efforts are useless when people have different moral foundations and each one is at the very rock bottom of understanding and explanation, which makes rational discourse impossible.

More here.

Steven Pinker: The Eight Levels of Charitable Giving

Anna May Wong will become the first Asian American to be on U.S. currency

Ashley Ahn on NPR:

The U.S. Mint will begin shipping coins featuring actress Anna May Wong on Monday, the first U.S. currency to feature an Asian American. Dubbed Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star, Wong championed the need for more representation and less stereotypical roles for Asian Americans on screen. Wong, who died in 1961, struggled to land roles in Hollywood in the early 20th century, a time of “yellowface,” when white people wore makeup and clothes to take on Asian roles, and anti-miscegenation laws, which criminalized interracial relationships.

The U.S. Mint will begin shipping coins featuring actress Anna May Wong on Monday, the first U.S. currency to feature an Asian American. Dubbed Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star, Wong championed the need for more representation and less stereotypical roles for Asian Americans on screen. Wong, who died in 1961, struggled to land roles in Hollywood in the early 20th century, a time of “yellowface,” when white people wore makeup and clothes to take on Asian roles, and anti-miscegenation laws, which criminalized interracial relationships.

The roles she did land were laced with racial stereotypes and she was underpaid, earning $6,000 for her top billed role in Daughter of the Dragon compared to Warner Oland’s $12,000, who only appeared in the first 23 minutes of the film. For Shanghai Express, Wong earned $6,000 while Marlene Dietrich made $78,166.

More here.

The Long and Winding Road to Eukaryotic Cells

Amanda Heidt in The Scientist:

Despite recent advances in the study of eukaryogenesis, much remains unresolved about the origin and evolution of the most complex domain of life.

This year, University of Paris-Saclay biologist Purificación López-García embarked with colleagues on a journey into life’s ancient past. The researchers traveled to the altiplanos of the northern Atacama Desert, high-altitude stretches of rocky soil and shrubbery in South America that are among the driest places in the world. Despite their inhospitable reputation, these plateaus may hold clues about the very origins of complex life. Amidst the dunes and barren mountains, there are pockets of life—warm, briny pools crusted over with colorful microbial mats of cyano-bacteria and archaea stacked atop one another like crepes. Long before Earth resembled its current state, López-García says, these microbial mats “were the forests of the past,” adding that scientists now use these clumps of microscopic life “as analogs of past ecosystems that certainly occurred at the time when eukaryotes first appear[ed].”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

A Vagabond Song

There is something in the autumn that is native to my blood—

Touch of manner, hint of mood;

And my heart is like a rhyme,

With the yellow and the purple and the crimson keeping time.

The scarlet of the maples can shake me like a cry

Of bugles going by.

And my lonely spirit thrills

To see the frosty asters like a smoke upon the hills.

There is something in October sets the gypsy blood astir;

We must rise and follow her,

When from every hill of flame

She calls and calls each vagabond by name.

by Bliss Carman

from Poetic Outlaws

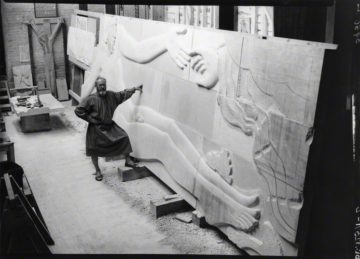

James Turrell: You Who Look

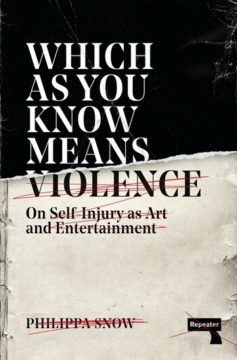

Performers Who Hurt Themselves, From Chris Burden To Jackass

Nikki Shaner-Bradford at Bookforum:

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch.

WHEN I FINISHED MY FIRST READ of Which as You Know Means Violence, critic Philippa Snow’s debut “on self-injury as art and entertainment,” I returned to my own cultural hallmark of suffering, the 2006 film adaptation of The Da Vinci Code. Reading Snow’s analysis of artist Chris Burden’s 1974 crucifixion atop a Volkswagen Beetle alongside the comical stunts of Johnny Knoxville and his squad of Jackass pranksters, I thought frequently of Paul Bettany’s fanatical Silas, who torments himself to such extremes that he plays at the brink of absurdity. Silas spends most of his screen time scurrying around church cloisters in monk’s robes and a bloody cilice, or flagellating his back in penance, a commitment to suffering so all-consuming and ridiculous that, by his third murderous jump-scare, it’s a challenge not to laugh mid-flinch.

more here.

Cooking with Taeko Kōno

Valerie Stivers at The Paris Review:

The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them.

The Japanese writer Taeko Kōno is a maestro of transgressive desire whose stories often—and deliciously—use food as a metaphor for sexual appetite. Kōno, who died in 2015, is considered one of Japan’s foremost feminist writers and one of its foremost writers of any kind. She won many of the country’s top literary prizes, including the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri. The single selection of her work in English, Toddler-Hunting & Other Stories, first published by New Directions in 1996 and translated by Lucy North and Lucy Lower, contains ten dark, deceptively simple stories about women who find the gender roles in Japanese society unbearable, and are warped by them.

Kōno’s heroines are abandoned wives, girlfriends who don’t want to marry, and women who lack maternal instincts. Her mothers are monsters. Her little girls feel “inner discomfort” with their gender. Most characters desire pain or humiliation during sex.

more here.

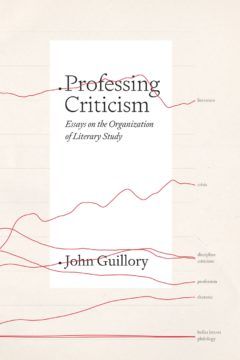

Monuments and Documents: Panofsky on the Object of Study in the Humanities

John Guillory at the website of the University of Chicago Press:

In this essay, I argue for a reorientation of discourse about the humanities to the objects of humanistic study rather than claims for their value or effect. Returning to an essay Erwin Panofsky published in 1940, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” I build on Panofsky’s rich distinction between “monuments” and “documents” as the two sides of the humanistic object of study. By “monuments,” Panofsky refers to all of those human artifacts, actions, or ideas that have urgent meaning for us in the present. By “document,” he refers to all of those traces or records by means of which we recover monuments. Monuments and documents bring the long time of human existence, past or future, into relation to the short time of human life, a relation that defines the objects of study in all the humanities and confirms the undeniable interest of that study.

In this essay, I argue for a reorientation of discourse about the humanities to the objects of humanistic study rather than claims for their value or effect. Returning to an essay Erwin Panofsky published in 1940, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline,” I build on Panofsky’s rich distinction between “monuments” and “documents” as the two sides of the humanistic object of study. By “monuments,” Panofsky refers to all of those human artifacts, actions, or ideas that have urgent meaning for us in the present. By “document,” he refers to all of those traces or records by means of which we recover monuments. Monuments and documents bring the long time of human existence, past or future, into relation to the short time of human life, a relation that defines the objects of study in all the humanities and confirms the undeniable interest of that study.

More here.

I am a recovering perfectionist.

I am a recovering perfectionist.