Drone: The Pilot’s Wife in Church

She wears a kind of doily hair-pinned to her crown,

her glory, the pastor says. She stands and the hymn

is sung along with the keyboard, the electric

guitar and the lead singer, heavy eyeliner, a tear

in the voice. The pastor stands at the rail, waiting

on sinners, scanning the congregation.

What should she pray? That her husband’s hands

should stop shaking? That he should stop working

on the Sabbath? That he should stop having those dreams,

stop getting up and playing video games in the dark?

Stop turning out the lights and then talking?

Stop not talking? Stop hating her for listening?

Stop killing those men who kill us? Stop killing

those children who cluster around them? Stop

the women who he must watch collect the bodies,

parts of bodies, who are themselves sometimes nothing

but bodies? Stop watching the bodies get into carts,

into trucks, into the trunks of cars? Stop being paid

for watching, for locating, for prosecuting,

for firing? Stop fighting for the insurance to pay,

for the VA to pay, for the government to pay.

What should she pray? How can God answer?

by Kim Garcia

from The Brooklyn Quarterly

IS A GAS GUZZLER

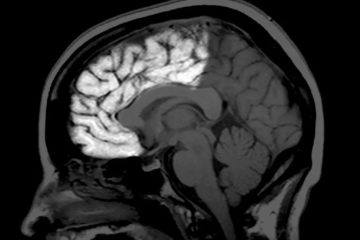

IS A GAS GUZZLER Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new

Scientists have discovered a glitch in our DNA that may have helped set the minds of our ancestors apart from those of Neanderthals and other extinct relatives. The mutation, which arose in the past few hundred thousand years, spurs the development of more neurons in the part of the brain that we use for our most complex forms of thought, according to a new

As forced migration in the wake of war and climate change continues, and various administrations attempt to additionally restrict the movement of people while further “freeing” the flow of capital, national borders, nativism, and a sense of cultural rootedness have re-emerged as acceptable topics in a globalized order that had until recently believed itself post-national. In the German-speaking world, where refugees have been met with varying degrees of enthusiasm depending on their provenance, national pride, long taboo following the Second World War, at least in Germany, is enjoying a comeback. As the last generation of perpetrators and victims dies and a newly self-confident, unproblematically nationalist generation comes to consciousness, it is again becoming possible to use a romantic, symbolically charged term like Heimat.

As forced migration in the wake of war and climate change continues, and various administrations attempt to additionally restrict the movement of people while further “freeing” the flow of capital, national borders, nativism, and a sense of cultural rootedness have re-emerged as acceptable topics in a globalized order that had until recently believed itself post-national. In the German-speaking world, where refugees have been met with varying degrees of enthusiasm depending on their provenance, national pride, long taboo following the Second World War, at least in Germany, is enjoying a comeback. As the last generation of perpetrators and victims dies and a newly self-confident, unproblematically nationalist generation comes to consciousness, it is again becoming possible to use a romantic, symbolically charged term like Heimat. Sughra Raza. Don’t Step On The Jewels, 2014.

Sughra Raza. Don’t Step On The Jewels, 2014.

technology will somehow amplify itself into a superintelligence and proceed to eliminate the human race, either inadvertently – as a side effect of some other project, such as creating paper clips (a standard example), or deliberately.

technology will somehow amplify itself into a superintelligence and proceed to eliminate the human race, either inadvertently – as a side effect of some other project, such as creating paper clips (a standard example), or deliberately.

Evil: Lost and Found

Evil: Lost and Found About eight years ago, I was in downtown Manhattan and went into a Warby Parker store, an eyewear retailer. I didn’t post anything on social media about it, but I did have location services enabled on Facebook. Later that day, Facebook started showing me ads for eyewear (something it had never done before.) How and why it did that wasn’t a giant leap of understanding, and I immediately turned location services off for Facebook. But of course, this was sticking one thumb in the crumbling dam that is my data privacy. I own an Alexa, and I have an iPhone, an Apple watch, and an iPad. And that’s just for starters. I use Google all day long, subscribe to multiple online publications, use Amazon regularly, have used Instacart in the past, and the list goes on.

About eight years ago, I was in downtown Manhattan and went into a Warby Parker store, an eyewear retailer. I didn’t post anything on social media about it, but I did have location services enabled on Facebook. Later that day, Facebook started showing me ads for eyewear (something it had never done before.) How and why it did that wasn’t a giant leap of understanding, and I immediately turned location services off for Facebook. But of course, this was sticking one thumb in the crumbling dam that is my data privacy. I own an Alexa, and I have an iPhone, an Apple watch, and an iPad. And that’s just for starters. I use Google all day long, subscribe to multiple online publications, use Amazon regularly, have used Instacart in the past, and the list goes on.

In the middle 1990’s my friend from the September Group, Sam Bowles, and I were invited by the Chicago-based MacArthur Foundation to form an inter-disciplinary and international research network to study the effects of Economic Inequality, with the two of us as co-Directors. I have known Sam for nearly four decades now. He is one of the brightest economists I know, with a large vision and wide-ranging interests that are often lacking in many bright economists. His landmark 2013 book Cooperative Species with his frequent co-author Herb Gintis uses experimental data and evolutionary science to show how genetic and cultural evolution has produced a human species where large numbers make sacrifices to uphold cooperative social norms. He himself has been socially alert and active in public causes all through his life, starting from writing background papers for Martin Luther King’s 1968 Poor People’s March to most recently providing leadership in the revamping of undergraduate Economics curriculum to include upfront non-standard issues like inequality, the environment and reciprocity and altruism in human behavior, and making it available free online worldwide. He is also one of the most generous and genial people I know.

In the middle 1990’s my friend from the September Group, Sam Bowles, and I were invited by the Chicago-based MacArthur Foundation to form an inter-disciplinary and international research network to study the effects of Economic Inequality, with the two of us as co-Directors. I have known Sam for nearly four decades now. He is one of the brightest economists I know, with a large vision and wide-ranging interests that are often lacking in many bright economists. His landmark 2013 book Cooperative Species with his frequent co-author Herb Gintis uses experimental data and evolutionary science to show how genetic and cultural evolution has produced a human species where large numbers make sacrifices to uphold cooperative social norms. He himself has been socially alert and active in public causes all through his life, starting from writing background papers for Martin Luther King’s 1968 Poor People’s March to most recently providing leadership in the revamping of undergraduate Economics curriculum to include upfront non-standard issues like inequality, the environment and reciprocity and altruism in human behavior, and making it available free online worldwide. He is also one of the most generous and genial people I know. Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost

Some words are much more frequent than others. For example, in a sample of almost  More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science

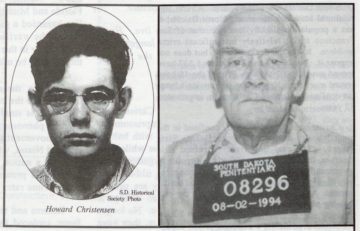

More than 500,000 years ago, the ancestors of Neanderthals and modern humans were migrating around the world when a fateful genetic mutation caused some of their brains to suddenly improve. This mutation, researchers report in Science In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “

In September of 1994, the editors and writers of The Angolite sought to identify everyone in America who had served two decades or more in prison in a piece titled, “ Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of

Although not originally part of the notorious gang of writers – Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and the late Christopher Hitchens – who made their names in the 70s and dominated the literary scene for much longer (too long, according to their critics), Rushdie arrived a few years later with the publication in 1981 of