by Michael Liss

I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president, who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me. —JFK

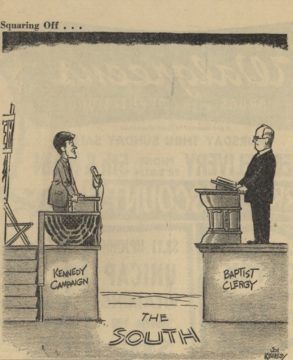

September 12, 1960. Just eight weeks before the 1960 election, and the Democratic candidate for President, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, finds himself before a crowd of roughly 300 Protestant clerics at a meeting of the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. He has been invited to explain his views on religion, more particularly, his religion.

To modern eyes, there is something surreal about this. Watch the clip in grainy black and white, read the speech, and you can’t help but be mesmerized. Why is he here? Kennedy was a war hero; he’d been a Congressman, a Senator, and a Pulitzer Prize winner. While it certainly could be argued that there might be better men for the job, surely JFK had achieved enough in his life to meet the qualifications for being a President.

Unless (and certainly many in the audience believed this) Kennedy could never be qualified. Unless, to use his own words on this day, he was just one of “40 million Americans [who] lost their chance of being president on the day they were baptized.”

Whatever his feelings, Kennedy and his team knew this moment, and moments like it, were inevitable. They had always known it, even before he entered the race. It was a reflection of what the journalist Theodore White called “the largest and most important division in American society, that between Protestants and Catholics.”

This division was everywhere, more so in some communities than others, but always present. Kennedy fought it all through the nominating process, every step on the journey, in small towns, at county fairs, at coffees and meets-and-greets, in Q&A sessions with local journalists, and in letters to the editors of local papers. Protestant ministers would raise it in their weekly bulletins to their congregants. Average voters would mention it without self-consciousness. A Catholic shouldn’t be President, because a Catholic was beholden to Rome. A Catholic could never separate Church from State.

America had been down this road once before, in 1928, when the Democrats nominated Catholic Al Smith, then the popular Governor of New York. Smith was overwhelmed by Herbert Hoover, losing 40 states, including the home state in which he was so popular. Come forward to 1960, and while a Depression and a World War may have changed some things, the conventional wisdom was that it hadn’t changed this. Catholics (and Jews) could be Senators, Governors, even Supreme Court Justices. But President—no, it was beyond reach.

When, in late 1959, Kennedy assembled his core team at the family compound in Hyannisport to organize and launch his run, everyone in the room was able to identify significant hurdles, and strategies to deal with them. But the Catholic thing was both unpredictable and uncontrollable. Kennedy could, and did, take a number of public positions that were contrary to “Catholic” wishes, but that didn’t rebut the presumption in many minds that he either couldn’t win, or shouldn’t win. No one had any idea how many Protestants who weren’t already committed Republicans might have considered, say, a Lyndon Johnson or Missouri’s Senator Stuart Symington, but would categorically rule out a JFK. Conversely, no one knew how strong the pull JFK, as a Catholic, would have on otherwise Republican-inclined Catholic voters. Complicating these calculations was a third point—Ike had routed Stevenson in 1956, gaining Democratic crossovers, and the hope was they could be brought home—would Democrats squander an opportunity by taking this big a chance? Finally, a fourth factor: with an uneven distribution of ethnic/religious groups across the country, the tipping point could be different from one state to another, leading to unanticipated results that could have substantial Electoral College impact.

Of course, Kennedy had to be nominated first, and that meant navigating an unusually treacherous path. In 1960, we hadn’t yet moved to a full primary-and-caucus system. Only 16 states had primaries, and, with the exception of Oregon, where candidates were enrolled automatically, entry was strictly optional. Several credible candidates avoided them entirely: LBJ, Symington, and twice Presidential loser (and possible reluctant-but-ready-to-serve-if-called) Adlai Stevenson.

The primaries’ influence was diluted further by the fact that “Favorite Sons” (usually a Governor or Senator) would run in their state’s primary or caucus for the purpose of controlling the state delegation (and doing a little bartering, for themselves or their states). Three states did that very thing—California (Governor Pat Brown), Florida (Senator George Smathers), and Ohio (Governor Michael DiSale). A fourth state, New Jersey, sent an unpledged slate of delegates, but included Governor Robert Meyner, who also thought he was Presidential material and saw himself as a fallback in a deadlocked Convention. These men were joined by the state and local-level power brokers who headed state delegations from places without primaries or caucuses.

So, if you were “just” a delegate, what were Conventions for besides doing what you were told, cheering on cue, and running around semi-sleepless in sweaty clothes with a drink in one hand and cigar in the other? Often, it was for the big boys to take their drinks and cigars into private rooms to determine just which one of the worthy candidates would grace the top of the ticket. That’s what the Favorite Sons With Ambition would hang their thin hopes on, and that’s what people like LBJ, Symington, and Stevenson counted on.

What did those big boys want? First and foremost, they wanted a winner—someone who could take the prize in November (and be able to honor all the deals they made). Could Kennedy be a winner? JFK’s own brain trust thought the big boys would say no—that a brokered convention would inevitably pick someone else.

That meant Kennedy had to show them otherwise—by amassing enough delegates to take it out of their hands. That started with quietly getting support from state-level power brokers (utilizing not just charm, but also the “Kennedy” tools at hand). It also required something bigger: it meant unifying (or at least mollifying) all the major components of a party that was in no way philosophically harmonious: Labor, farmers, big-city voters and the machine string pullers who quietly led them. Then add the not-so-Solid South and bits and pieces of other groups who had been swept into FDR’s New Deal coalition and hadn’t quite left through the Eisenhower years.

Each of these constituent interests would be watching for JFK’s positions that mattered to them, and the big boys would be watching that and more. How would Kennedy navigate issues that he simply could not control? He would be the youngest President ever to be elected, at a time when the world seemed particularly dangerous. He had no executive experience—he was a Senator, and, in the 20th Century, sitting Senators hadn’t had a lot of luck going directly to the Oval Office. And….he was a Catholic.

JFK’s brain trust thought they could deal with the age issue in part by showing its flip side, his “youth and viggah.” Kennedy was tireless, going not just to big rallies and high-profile speeches, but to anywhere votes could be found. Gravitas came from his Pulitzer for “Profiles in Courage” and his more recent work on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. But the Catholicism part, as frustrating as it was, would have to be answered over and over, often to people whose minds were permanently closed.

Kennedy entered and won New Hampshire—he was basically uncontested in his neighboring state, but the bigger questions revolved around Wisconsin (April 5) and West Virginia (May 10). There was a good reason why serious candidates like LBJ and Symington skipped the primaries altogether—an early loss in a truly competitive primary could lead to an early end to their candidacies. Notwithstanding that, if Kennedy was right in his analysis that he’d get the cold shoulder at the Convention without the delegate strength to back him up, the primaries were a place to get some.

All that said, Wisconsin and West Virginia were particularly fraught: Wisconsin had a population and economic base similar to competitor Hubert Humphrey’s Minnesota. It was also majority Protestant, but with a significant Catholic population. That made it a minefield: Kennedy could lose outright to a well-liked neighbor, or he could win in such a manner that would cast doubt on his general appeal. As for West Virginia, outside of its pervasive and appalling poverty, it was also 95% Protestant. Not prime ground for a Harvard-educated member of the Boston-Catholic elites.

Kennedy barnstormed Wisconsin—he was everywhere, and his superior resources swamped Humphrey’s meager campaign chest (at one point, Humphrey had to write a $750 personal check to secure airtime, as his wife looked on with a wince). Polling showed JFK catching him and then opening a large lead. The Kennedy people were optimistic going into the election—perhaps he’d sweep all of the state’s Congressional Districts. It wasn’t to be. Although JFK won about 55% of the vote, he lost the heavily Protestant 3rd, 4th, 9th, and 10th CDs. While Humphrey’s campaign was damaged by the loss, the results highlighted JFK’s vulnerability, and essentially forced his hand. He had to contest West Virginia, where word of his Catholicism had helped turn an early polling lead into a 20-point deficit. But before that, he had to take head on what was becoming the “narrative” in the media. On April 21, he addressed the American Society of Newspaper Editors (link here)

The speech was tightly reasoned and made an intellectually compelling case for fairness, but one wonders if it changed minds in the room. There were apparently no questions from the audience, and it can’t be said to have had a measurable effect on the news coverage afterwards. The press continued to let religion crowd out more substantive issues.

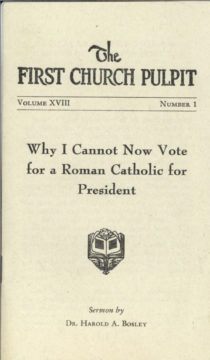

Perhaps the media was too focused on JFK’s religion, but it isn’t as if the topic didn’t keep coming up. On April 28, the convention of the American Council of Christian Churches passed a resolution disapproving a Catholic as President. A day later, The National Association of Evangelicals adopted one suggesting that a Catholic President would not resist the demands/commands of the hierarchy. On May 20, the Southern Baptist Convention did something in the same vein. While other organizations took a broader view (both The Quadrennial Methodist General Conference and the general assembly of the Southern Presbyterian Church considered, but rejected similar initiatives), the mere fact that the subject was being discussed continued to make it newsworthy.

The Kennedy team had no choice but to plunge ahead, and their best asset, the candidate himself, was doing a spectacular job on the ground in West Virginia. He went to every corner of the state, saw everything, and came away with a firsthand picture of back-breaking poverty, houses without running water, schools without the most basic resources, ravaged lands and worn-out company towns. West Virginians saw him—Catholic, yes, but someone who showed genuine empathy. There are some remarkable images of the immaculately dressed JFK speaking to crowds in rough, probably home-made clothes, sitting with ordinary people, listening to their cares. They responded with 61% of the vote, effectively ending Humphrey’s campaign (he withdrew right afterwards) and emphatically showing JFK could appeal outside his base.

With Humphrey out, West Virginia cleared the field of meaningful primary opposition, and Kennedy began to roll, both in the remaining primaries and in recruiting delegates. As for the rest of the candidates, Kennedy’s team simply out-charmed, out-organized, and, where necessary, out-fought them. After some real drama at the Convention caused mostly by Stevenson’s anguished last gasp (which included a plea by Eleanor Roosevelt for JFK to accept the Veep spot), Kennedy secured the nomination on July 14th.

Out of the frying pan, into the general-election fire. However much a theoretical Kennedy candidacy had riled up those who objected to him on religious grounds, the reality of the nomination, and the real possibility of his election, amped up the anxiety. It remained the constant question of the media, and a constant concern of some voters. It also brought off the sidelines some prominent minsters and theologians who might have privately been voicing their views, but now felt they had to speak out. America could not have a President beholden to a foreign power.

On September 7, a new organization emerged, the “National Citizens Conference For Religious Freedom.” It consisted of approximately 150 Protestant ministers and was chaired by one of the most famous (and popular) religious figures in America, the Reverend Norman Vincent Peale. Peale’s “The Power Of Positive Thinking” had sold millions of copies and been translated into roughly 40 languages.

The Conference’s statement, some of it in the form of a series of questions directed at JFK, was objectively harsh and presumptively rejected any possible rebuttal. In the moment, it just went too far, and immediately induced a counter-reaction. Peale himself came in for sharp criticism, and several newspapers dropped his spiritual advice column. He quickly backed away from both the statement, and the Committee itself.

Why did Peale do it in the first place? He was a friend of Richard Nixon, who, after he moved to New York, occasionally attended services at Peale’s Marble Collegiate Church, but there’s no evidence that Nixon asked. The best answer is probably the most obvious: Prejudice against Catholics was not confined to the fringes.

With this as backdrop and with the election looking to be very close, Kennedy headed into the lion’s den. Ignoring the concerns of some of his advisors, he went to Texas to speak to, and take questions from, the Greater Houston Ministerial Association.

Kennedy and his chief speechwriter, Ted Sorenson, worked into the speech the same themes that candidate Kennedy had been repeating everywhere, and there was certainly an echo of his April remarks before the American Society of Newspaper Editors. Yet, there was something subtly different about this speech, something tone-appropriate for an audience that largely ranged from skeptical to outright hostile. It was not only cerebral but aspirational. There were touches of Lincoln in it, calling people to reach for something higher.

I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote; where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference; and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the president who might appoint him or the people who might elect him.

I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish; where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the Pope, the National Council of Churches or any other ecclesiastical source; where no religious body seeks to impose its will directly or indirectly upon the general populace or the public acts of its officials; and where religious liberty is so indivisible that an act against one church is treated as an act against all.

That is the kind of America in which I believe. And it represents the kind of presidency in which I believe—a great office that must neither be humbled by making it the instrument of any one religious group, nor tarnished by arbitrarily withholding its occupancy from the members of any one religious group. I believe in a president whose religious views are his own private affair, neither imposed by him upon the nation, or imposed by the nation upon him as a condition to holding that office.

It took Kennedy 10 minutes to deliver those remarks, and there was a Q&A session that followed for roughly another 30. If he had come to convert his audience, he almost certainly didn’t. But, in terms of showing stature, maturity, balance, and more than a little courage, he’d done exactly what he needed to do. Sam Rayburn, then Speaker of the House, and a Kennedy doubter, said afterwards, “As they say in my part of Texas, he ate’em blood raw.”

One speech was never going to be enough, and Kennedy’s religion continued to be an issue through the rest of the campaign. Again and again, the same themes recurred: A Catholic had to obey the church hierarchy, he could never keep church and state separate, he would skew policy in favor of Catholic priorities, and, ultimately, he would let the Pope decide the biggest of issues. No matter what words Kennedy used, no matter how he voted in the Senate, he would never be able to shake off the suspicions, or those willing to act on them. The National Association of Evangelicals, for example, attempted to make Reformation Sunday (October 30, 1960) a day of anti-Catholic and anti-Kennedy sermons and rallies. Perhaps as a result of what happened in Houston, their success was limited.

The race was tight all the way and tightened even more as it approached Election Day. On October 19, fate decided to intercede a bit more. That other “great divide” in American life, between White and Black, appeared. Martin Luther King was arrested with 52 others for sitting in an Atlanta department store’s dining room. The following Monday, all but King were released. He was found guilty of a traffic violation and sentenced to four months’ hard labor at a state penitentiary. There was every reason to think King would never make it out alive, and, if he were lynched, every reason to expect even more violence. King’s wife Coretta was six months pregnant at the time and was convinced her husband was doomed.

The moral dilemma for the Kennedy campaign was acute. Bobby Kennedy had heard from three Democratic Governors that, if JFK ever tried to intervene on King’s behalf, their states would be lost to him. But Coretta King was almost certainly right, and what the judge had done to King was clearly wrong. Sargent Shriver, then head of the Civil Rights Section of the Kennedy campaign, tracked down JFK at a hotel in Chicago, and Kennedy responded immediately. He called Mrs. King to assure her of his concern and support, and, the day after, Bobby called the judge directly. King was released, and it was like a lightning bolt in the Black community. King’s father, The Reverend Martin Luther King Sr., who had come out for Nixon a few weeks previously on religious grounds, now publicly switched. “This man was willing to wipe the tears from my daughter[-in-law]’s eyes,” he said. “I’ve got a suitcase of votes, and I’m going to take them to Mr. Kennedy.” There is no way to quantify how many votes were in Dr. King’s suitcase, but Blacks surely switched in some numbers to Kennedy. Their votes were difference-makers for him in swing states Illinois, Michigan and South Carolina.

The election was unbearably close. More than a dozen states were decided by less than two percent. Hawaii went to a recount before going for Kennedy by 115 votes. There is no way to disaggregate the statistics in a way that can fully account for the impact of the Protestant-Catholic divide, but it surely played a significant role.

We can leave Kennedy with the last word on what it means to be a President:

But if, on the other hand, I should win the election, then I shall devote every effort of mind and spirit to fulfilling the oath of the presidency—practically identical, I might add, to the oath I have taken for 14 years in the Congress. For without reservation, I can ‘solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States, and will to the best of my ability preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution, so help me God.’