Gordon Peake and Miranda Forsyth in Aeon:

Gordon Peake and Miranda Forsyth in Aeon:

We live in Canberra and Washington, DC, two stately capital cities that embody all the trappings and the ethos of the bureaucratic state. With their monuments, statues and symmetrical lines, the architects of both cities dreamt them as manifestations of the rational administrations that would work there. Imposing government buildings are the dominant architectural feature of both places, rising like redwood plantation trees in a planned forest. Irrespective of the decade or the party in charge, policies and plans that emerge from these buildings have the hallmarks of a planned forest, too: ordered, consistent and ostensibly guided by clear rules.

In terms of their scale, size and administrative grandeur, Canberra and Washington, DC are as different as can be from another city where we have both spent time: little Buka Town, the tumbledown, sun-scorched capital of Bougainville, presently an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea (and possibly soon the world’s newest country, after a 2019 referendum on independence, in which 97.7 per cent of the population voted in favour). In Buka, there is no capacious national repository to store administrative documents: the Bougainville government’s archives are a rusty-red shipping container into which papers get chucked periodically.

Ironically, though, it was in Buka that we found ourselves constantly bumping into the ghost of Max Weber, considered the father of bureaucracy (although he himself might bristle at that designation).

More here.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor. I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

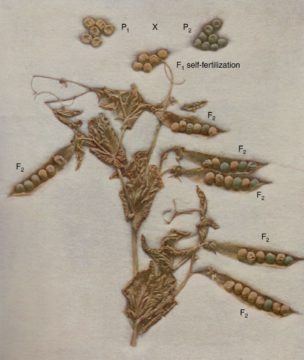

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread. There are few historical records concerning Gregor Johann Mendel and his work, so theories abound concerning his motivation. These theories range from Fisher’s view that Mendel was testing a fully formed previous theory of inheritance to Olby’s view that Mendel was not interested in inheritance at all, whereas textbooks often state his motivation was to understand inheritance. In this Perspective, we review current ideas about how Mendel arrived at his discoveries and then discuss an alternative scenario based on recently discovered historical sources that support the suggestion that Mendel’s fundamental research on the inheritance of traits emerged from an applied plant breeding program. Mendel recognized the importance of the new cell theory; understanding of the formation of reproductive cells and the process of fertilization explained his segregation ratios. This interest was probably encouraged by his friendship with Johann Nave, whose untimely death preceded Mendel’s first 1865 lecture by a few months. This year is the 200th anniversary of Mendel’s birth, presenting a timely opportunity to revisit the events in his life that led him to undertake his seminal research. We review existing ideas on how Mendel made his discoveries, before presenting more recent evidence.

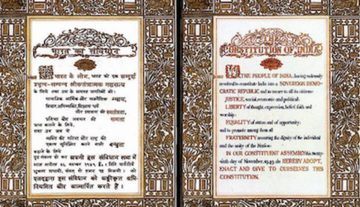

There are few historical records concerning Gregor Johann Mendel and his work, so theories abound concerning his motivation. These theories range from Fisher’s view that Mendel was testing a fully formed previous theory of inheritance to Olby’s view that Mendel was not interested in inheritance at all, whereas textbooks often state his motivation was to understand inheritance. In this Perspective, we review current ideas about how Mendel arrived at his discoveries and then discuss an alternative scenario based on recently discovered historical sources that support the suggestion that Mendel’s fundamental research on the inheritance of traits emerged from an applied plant breeding program. Mendel recognized the importance of the new cell theory; understanding of the formation of reproductive cells and the process of fertilization explained his segregation ratios. This interest was probably encouraged by his friendship with Johann Nave, whose untimely death preceded Mendel’s first 1865 lecture by a few months. This year is the 200th anniversary of Mendel’s birth, presenting a timely opportunity to revisit the events in his life that led him to undertake his seminal research. We review existing ideas on how Mendel made his discoveries, before presenting more recent evidence. AS SOMEONE WHO grew up in India in the early 2000s, after the once-colonized country had opened itself to the global economy, one thing was clear to me. Aspiration and English were synonymous. Both were essential. This lesson was drilled into me at my missionary-run English-medium high school in New Delhi. Whether we dreamed of becoming doctors or engineers or corporate hotshots, we were repeatedly told that we needed to have English. Students were penalized for speaking in any language other than English, and our pronunciations were disciplined in preparation for roles no one doubted we would take on. Away from the institutional ear, my peers and I still cherished our other languages, to varying degrees. But, for the most part, we learned to joke, dream, rebel, and obey in English.

AS SOMEONE WHO grew up in India in the early 2000s, after the once-colonized country had opened itself to the global economy, one thing was clear to me. Aspiration and English were synonymous. Both were essential. This lesson was drilled into me at my missionary-run English-medium high school in New Delhi. Whether we dreamed of becoming doctors or engineers or corporate hotshots, we were repeatedly told that we needed to have English. Students were penalized for speaking in any language other than English, and our pronunciations were disciplined in preparation for roles no one doubted we would take on. Away from the institutional ear, my peers and I still cherished our other languages, to varying degrees. But, for the most part, we learned to joke, dream, rebel, and obey in English. In the late afternoon of September 21, 2018, I exited my New York apartment building carrying a folding table and a big sign reading GRAMMAR TABLE. I crossed Broadway to a little park called Verdi Square, found a spot at the northern entrance to the Seventy-Second Street subway station, propped up my sign, and prepared to answer grammar questions from passersby.

In the late afternoon of September 21, 2018, I exited my New York apartment building carrying a folding table and a big sign reading GRAMMAR TABLE. I crossed Broadway to a little park called Verdi Square, found a spot at the northern entrance to the Seventy-Second Street subway station, propped up my sign, and prepared to answer grammar questions from passersby. INTERPRETING ANCIENT DNA

INTERPRETING ANCIENT DNA I remember all too well that day early in the pandemic when we first received the “stay at home” order. My attitude quickly shifted from feeling like I got a “snow day” to feeling like a bird in a cage. Being a person who is both extraverted by nature and not one who enjoys being told what to do, the transition was pretty rough.

I remember all too well that day early in the pandemic when we first received the “stay at home” order. My attitude quickly shifted from feeling like I got a “snow day” to feeling like a bird in a cage. Being a person who is both extraverted by nature and not one who enjoys being told what to do, the transition was pretty rough. “O

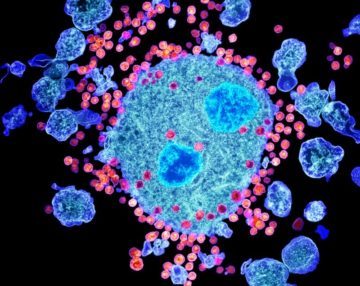

“O An injectable drug that protects people at high risk of HIV infection has been recommended for use by the World Health Organization (WHO). Cabotegravir (also known as CAB-LA), which is given every two months, was initially approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in December 2021.

An injectable drug that protects people at high risk of HIV infection has been recommended for use by the World Health Organization (WHO). Cabotegravir (also known as CAB-LA), which is given every two months, was initially approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in December 2021. Care work — tending to the sick, the very young or the very old — has long been denied the kind of recognition (and remuneration) that

Care work — tending to the sick, the very young or the very old — has long been denied the kind of recognition (and remuneration) that  Ever since ancient Uruk, the world’s first major city, founded around 4000

Ever since ancient Uruk, the world’s first major city, founded around 4000  Melinda Cooper in Phenomenal World:

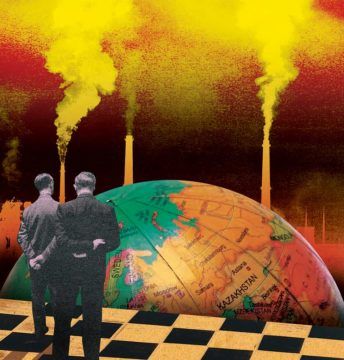

Melinda Cooper in Phenomenal World: Thea Riofrancos in The Nation (illustration by Tim Robinson):

Thea Riofrancos in The Nation (illustration by Tim Robinson): Gordon Peake and Miranda Forsyth in Aeon:

Gordon Peake and Miranda Forsyth in Aeon: