Matthew Mutter in The Hedgehog Review:

For years, I played basketball with a humanities skeptic. He was an endowment manager at the Ivy League university from which he had graduated with a degree in economics. He knew I was a professor of literature, and one day he asked what I taught—and did I by any chance teach Moby-Dick? I nodded, and he said, “You don’t believe the hype, do you?” His proudest moment in college had come when, required to read the novel for a first-year class, he developed a firm belief that Moby-Dick’s reputation was explainable chiefly by its obscurity. The emperor had no clothes: The novel was taught because it was revered, and revered because it was taught. Baffled readers took their incomprehension as a sign of its elusive greatness. Teachers followed blind tradition and enjoyed the aura of solemn stupefaction.

For years, I played basketball with a humanities skeptic. He was an endowment manager at the Ivy League university from which he had graduated with a degree in economics. He knew I was a professor of literature, and one day he asked what I taught—and did I by any chance teach Moby-Dick? I nodded, and he said, “You don’t believe the hype, do you?” His proudest moment in college had come when, required to read the novel for a first-year class, he developed a firm belief that Moby-Dick’s reputation was explainable chiefly by its obscurity. The emperor had no clothes: The novel was taught because it was revered, and revered because it was taught. Baffled readers took their incomprehension as a sign of its elusive greatness. Teachers followed blind tradition and enjoyed the aura of solemn stupefaction.

“Now mystery had brushed them with her wing; they had heard the voice of authority”: So Virginia Woolf’s Londoners felt when they spotted a car, its windows curtained, transporting royalty. The intimations of majesty are pleasant, but there is a deeper pleasure in unmasking authority. The memory of pulling back the curtain still pleased my basketball partner fifteen years later.

More here.

A reader who opens a volume of Šalamun to any page is likely to find a startling line: “Bees rustle like a fifth column”; “I am a volcano that needs no sandals.” His images cascade in bewildering but thrilling torrents: “Wreaths shut in butter, shut in a glassy / casket in the hydra’s snout under the tree-tooth, / left shadow, microbes, blown up by / Job, flushed tender shivering gelatinous / Law morphing into socage.” Tonally, he can shift abruptly from the silly (“the soul of earth jacks off the skeleton key”) to the breathtaking (“My heart / beats like the heart of a hare who will die of fear”). He is a poet of wild and strange delights; to love Šalamun, readers must want to be invited into uncharted territory.

A reader who opens a volume of Šalamun to any page is likely to find a startling line: “Bees rustle like a fifth column”; “I am a volcano that needs no sandals.” His images cascade in bewildering but thrilling torrents: “Wreaths shut in butter, shut in a glassy / casket in the hydra’s snout under the tree-tooth, / left shadow, microbes, blown up by / Job, flushed tender shivering gelatinous / Law morphing into socage.” Tonally, he can shift abruptly from the silly (“the soul of earth jacks off the skeleton key”) to the breathtaking (“My heart / beats like the heart of a hare who will die of fear”). He is a poet of wild and strange delights; to love Šalamun, readers must want to be invited into uncharted territory. Owen Hatherley blithely claims that this massive tour de force is ‘a guide to the place … you’re visiting, or a place you want to visit’. Pull the other one, squire. The notion of Owen Hatherley, Tripadvisor, is sheerly preposterous, though it may appeal to a tremulous publisher figuring out how to market this behemoth. He is really a polemicist, ready to take issue with anyone, including himself. His insistent invitations to look are heavy with allusions, catholic comparisons and quiet asides. The result of his tireless labour is an oblique, partial, lopsided survey of Britain throughout the long modernist century; and no matter what a platoon of celluloid collars and triple-breasted waistcoats may have wished for, modernism did triumph, in many guises. Its variety goes unnoticed by its antagonists, who have no ability to discern the kinship of much modernist architecture to its medieval and Victorian precursors. What they do have, in abundance, is torpid prejudice. This approximate gazetteer will not convince the obstinate to change their minds. But that really is not its point. It is a gorgeous treat for the already converted and, maybe, for those impaled on the spikes of equivocation. Hatherley’s only historical blunder is to describe Art Nouveau as ‘a mechanized sub-species of the Arts and Crafts’. The latter was pretty much exclusively English; the former was its flashy contemporary in places such as Belgium, Catalonia and Nancy. They hardly infected each other.

Owen Hatherley blithely claims that this massive tour de force is ‘a guide to the place … you’re visiting, or a place you want to visit’. Pull the other one, squire. The notion of Owen Hatherley, Tripadvisor, is sheerly preposterous, though it may appeal to a tremulous publisher figuring out how to market this behemoth. He is really a polemicist, ready to take issue with anyone, including himself. His insistent invitations to look are heavy with allusions, catholic comparisons and quiet asides. The result of his tireless labour is an oblique, partial, lopsided survey of Britain throughout the long modernist century; and no matter what a platoon of celluloid collars and triple-breasted waistcoats may have wished for, modernism did triumph, in many guises. Its variety goes unnoticed by its antagonists, who have no ability to discern the kinship of much modernist architecture to its medieval and Victorian precursors. What they do have, in abundance, is torpid prejudice. This approximate gazetteer will not convince the obstinate to change their minds. But that really is not its point. It is a gorgeous treat for the already converted and, maybe, for those impaled on the spikes of equivocation. Hatherley’s only historical blunder is to describe Art Nouveau as ‘a mechanized sub-species of the Arts and Crafts’. The latter was pretty much exclusively English; the former was its flashy contemporary in places such as Belgium, Catalonia and Nancy. They hardly infected each other. Infectious diseases such as malaria remain a leading cause of death in many regions. This is partly because people there don’t have access to medical diagnostic tools that can detect these diseases (along with a range of non-infectious diseases) at an early stage, when there is more scope for treatment. It’s a challenge scientists have risen to, with a goal to democratize

Infectious diseases such as malaria remain a leading cause of death in many regions. This is partly because people there don’t have access to medical diagnostic tools that can detect these diseases (along with a range of non-infectious diseases) at an early stage, when there is more scope for treatment. It’s a challenge scientists have risen to, with a goal to democratize  In 2013, the French economist Thomas Piketty, in his best seller “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” a book eagerly received in the wake of the 2008 economic collapse, put forth the notion that returns on capital historically outstrip economic growth (his famous r>g formula). The upshot? The rich get richer, while the rest of us stay stuck in the mud. Now, nearly a decade later, Piketty is set to publish “A Brief History of Equality,” in which he argues that we’re on a trajectory of greater, not less, equality and lays out his prescriptions for remedying our current corrosive wealth disparities. (In short: Tax the rich.) If the line from one book to the other looks slightly askew given the state of the world, then, Piketty suggests, you’re looking from the wrong vantage point. “I am relatively optimistic,” says Piketty, who is 50, “about the fact that there is a long-run movement toward more equality, which goes beyond the little details of what happens within a specific decade.”

In 2013, the French economist Thomas Piketty, in his best seller “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” a book eagerly received in the wake of the 2008 economic collapse, put forth the notion that returns on capital historically outstrip economic growth (his famous r>g formula). The upshot? The rich get richer, while the rest of us stay stuck in the mud. Now, nearly a decade later, Piketty is set to publish “A Brief History of Equality,” in which he argues that we’re on a trajectory of greater, not less, equality and lays out his prescriptions for remedying our current corrosive wealth disparities. (In short: Tax the rich.) If the line from one book to the other looks slightly askew given the state of the world, then, Piketty suggests, you’re looking from the wrong vantage point. “I am relatively optimistic,” says Piketty, who is 50, “about the fact that there is a long-run movement toward more equality, which goes beyond the little details of what happens within a specific decade.”

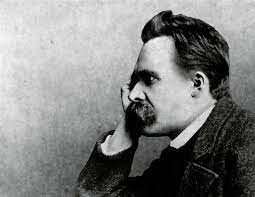

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Friedrich Nietzsche is my “desert island philosopher.” Guests, or “castaways” on BBC Radio 4’s long running program “Desert Island Discs” are allowed to take to their desert island, in addition to eight pieces of music, a text of religious or philosophical significance. Many accept the bible as the default option. For me, the choice is a no brainer: I’d take the works of Nietzsche.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Leandro Erlich. “BÂTIMENT”, 2004, La Nuit Blanche, Paris, France.

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

Language has an important role to play in national identity. One only has to think about the

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I’m not sure anyone has ever figured out how to write about music. This is a dangerous statement to make, and I’m sure readers will be quick to point out writers who have been able to capture something as intangible as sound via the written word. This would be a happy result of this article, and I welcome any and all suggestions. I should also say that I don’t mean there are no good music writers; there are, and I have certain writers I follow and read. But the question of how to write about music remains a tricky one.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed.

I got an incredible break when I was thirteen. We moved to Seattle and I entered public school in the sixth grade, after five years of Catholic education. The impact of the change in fortune was all the greater since I had no particular expectations, a good example of the principle that you can never know when things are about to change for the better. It was not just that my least favorite subject, religion, was no longer on the curriculum–that was the least of it. My new school exuded a different mood, much more open, so different to the reform school atmosphere I had become accustomed to. My life began to feel truly blessed. The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.

The interest of both Masahiko Aoki and Gérard Roland in institutional economics easily shaded into comparative analysis of economic systems, including different varieties of capitalism and socialism. Since my student days I have been acutely interested in comparative systems and their political economy. In this context like Aoki and Roland I have closely followed developments in China. When I was growing up in Kolkata the leftists around me used to say that the Chinese were better socialists than us, now in the last three decades I have heard in all quarters that the Chinese are better capitalists than us. To reconcile the two I sometimes tell people that if the Chinese are better capitalists now this is partly because they were better socialists then. This is not an entirely flippant comment. By the end of the Mao regime in middle 1970’s, before Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms started, Chinese performance indicators in basic health, education and rural electrification showed levels unattained by India even by two decades later. This gave China a head start in providing the basis of capitalist industrialization.