Month: May 2022

Catherine Spaak (1945 – 2022) Actress And Singer

Naomi Judd (1946 – 2022) Country Music Singer And Actress

‘The Premonitions Bureau’ by Sam Knight

Anthony Cummins at The Guardian:

Sam Knight is a prizewinning British New Yorker journalist whose features and profiles fizz with doggedly chased-down detail distilled into compelling narrative, whether he’s writing about Ronnie O’Sullivan, the £8bn-a-year sandwich industry or preparations for the death of the Queen (“Operation London Bridge”). The Premonitions Bureau, his first book, showcases the gifts that make him so endlessly readable. A richly researched feat of compression, it tells a tantalising tale of the unlikely interplay between the press, psychiatry and the paranormal in Britain during the late 1960s.

Sam Knight is a prizewinning British New Yorker journalist whose features and profiles fizz with doggedly chased-down detail distilled into compelling narrative, whether he’s writing about Ronnie O’Sullivan, the £8bn-a-year sandwich industry or preparations for the death of the Queen (“Operation London Bridge”). The Premonitions Bureau, his first book, showcases the gifts that make him so endlessly readable. A richly researched feat of compression, it tells a tantalising tale of the unlikely interplay between the press, psychiatry and the paranormal in Britain during the late 1960s.

Knight’s central character (so fluently does he tell his outlandish story, it’s hard not to think of it as a novel) is John Barker, a Cambridge-educated psychiatrist whose interest in clairvoyance led him to pitch the Evening Standard late in 1966 with the idea of a “Premonitions Bureau”, by which readers would come forward with portents of catastrophe, such as that year’s deadly landslide at Aberfan.

more here.

Carlo Rovelli Explores Beyond Physics

Nicholas Cannariato at the NYT:

The nature of time. Black holes. Ancient philosophers. The struggle for democracy. Climate change. Buddhist philosophy. In his new collection of essays and articles, Carlo Rovelli, one of the world’s most renowned physicists, broadens his writing to include questions of politics, justice and how we live now.

The nature of time. Black holes. Ancient philosophers. The struggle for democracy. Climate change. Buddhist philosophy. In his new collection of essays and articles, Carlo Rovelli, one of the world’s most renowned physicists, broadens his writing to include questions of politics, justice and how we live now.

“I look at myself as much more than a physicist,” he said in an interview at his home in London, Ontario, on a cold, calm day in February. The new book, “There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness,” published by Riverhead on May 10, is the result of all his “wandering around and being curious in this space of culture at large,” he added.

There is a thread, however, through the myriad topics he covers: the interdependence of all things — and what makes that interdependence profound.

more here.

Saturday Poem

A Birthday Poem

Just past dawn, the sun stands

with its heavy red head

in a black stanchion of trees,

waiting for someone to come

with his bucket

for the foamy white light,

and then a long day in the pasture.

I too spend my days grazing,

feasting on every green moment

till darkness calls,

and with the others

I walk away into the night,

swinging the little tin bell

of my name.

by Ted Kooser

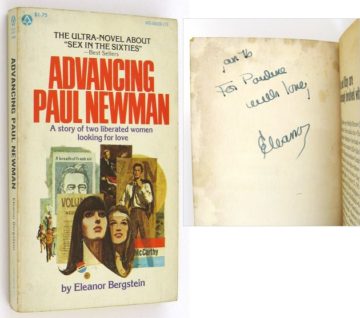

On Liberated Women Looking for Love

Elisa Gonzalez in The Paris Review:

I became aware of Advancing Paul Newman, Eleanor Bergstein’s 1973 debut novel, through Anatole Broyard’s dismissive review, which I came across in some undirected archival wandering. His grating condescension spurred me to read the novel—one of the best minor rebellions I’ve ever undertaken. (Bergstein is best known for writing the movie Dirty Dancing.) “This is the story of two girls, each of whom suspected the other of a more passionate connection with life,” she writes of the protagonists, best friends Kitsy and Ila. The romance of their friendship holds together everything else: trips to Europe to collect experiences (which, of course, often disappoint), becoming or failing to become writers, love affairs and marriages and divorces, their idealistic campaigning for the anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968. But Advancing Paul Newman is not simply a story of friendship, albeit one between two complicated women. The book is also gorgeously deranged and witty, told in fragments and leaps. “Don’t find me poignant, you ass,” Kitsy snaps at her ex when he happens upon her eating alone in a restaurant. After bad sex in Italy, she says matter-of-factly, “This was a good experience because now I know what it feels like to have my flesh crawl.” Ila is “glorious when in love, undistinguished when not in love,” and sleeps with two men on the day of Kitsy’s wedding. “There were reasons.”

I became aware of Advancing Paul Newman, Eleanor Bergstein’s 1973 debut novel, through Anatole Broyard’s dismissive review, which I came across in some undirected archival wandering. His grating condescension spurred me to read the novel—one of the best minor rebellions I’ve ever undertaken. (Bergstein is best known for writing the movie Dirty Dancing.) “This is the story of two girls, each of whom suspected the other of a more passionate connection with life,” she writes of the protagonists, best friends Kitsy and Ila. The romance of their friendship holds together everything else: trips to Europe to collect experiences (which, of course, often disappoint), becoming or failing to become writers, love affairs and marriages and divorces, their idealistic campaigning for the anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968. But Advancing Paul Newman is not simply a story of friendship, albeit one between two complicated women. The book is also gorgeously deranged and witty, told in fragments and leaps. “Don’t find me poignant, you ass,” Kitsy snaps at her ex when he happens upon her eating alone in a restaurant. After bad sex in Italy, she says matter-of-factly, “This was a good experience because now I know what it feels like to have my flesh crawl.” Ila is “glorious when in love, undistinguished when not in love,” and sleeps with two men on the day of Kitsy’s wedding. “There were reasons.”

When she has a story accepted by The New Yorker, the proofs are returned with only one sentence intact: “Madam, the gentleman across the aisle is staring at my upper thighs.” The novel’s title comes from one of Kitsy and Ila’s duties in the McCarthy campaign: to arrive in advance at Paul Newman’s public appearances on behalf of McCarthy. They act as political fluffers, exciting the crowd and leaving for the next event just as Newman’s car pulls up. (Spoiler: they never meet him.) “Why in the world are you doing that, Miss Bergstein?” Broyard asked, frustrated, in his review. I think I know: the search for a passionate connection with life is chaotic; the lives of young women encompass more than a man thinks they should.

More here.

Breaking into the black box of artificial intelligence

Neil Savage in Nature:

In February 2020, with COVID-19 spreading rapidly around the globe and antigen tests hard to come by, some physicians turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to try to diagnose cases1. Some researchers tasked deep neural networks — complex systems that are adept at finding subtle patterns in images — with looking at X-rays and chest computed tomography (CT) scans to quickly distinguish between people with COVID-based pneumonia and those without2. “Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a race to build tools, especially AI tools, to help out,” says Alex DeGrave, a computer engineer at the University of Washington in Seattle. But in that rush, researchers did not notice that many of the AI models had decided to take a few shortcuts.

In February 2020, with COVID-19 spreading rapidly around the globe and antigen tests hard to come by, some physicians turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to try to diagnose cases1. Some researchers tasked deep neural networks — complex systems that are adept at finding subtle patterns in images — with looking at X-rays and chest computed tomography (CT) scans to quickly distinguish between people with COVID-based pneumonia and those without2. “Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a race to build tools, especially AI tools, to help out,” says Alex DeGrave, a computer engineer at the University of Washington in Seattle. But in that rush, researchers did not notice that many of the AI models had decided to take a few shortcuts.

The AI systems honed their skills by analysing X-rays that had been labelled as either COVID-positive or COVID-negative. They would then use the differences they had spotted between the images to make inferences about new, unlabelled X-rays. But there was a problem. “There wasn’t a lot of data available at the time,” says DeGrave.

More here.

Friday Poem

Untitled

The astonishing reality of things

Is my discovery every day.

Each thing is what it is,

And it’s hard to explain to someone how happy this

… makes me,

And how much this suffices me.

All it takes to be complete is to exist.

I’ve written quite a few poems,

I’ll no doubt write many more,

And this is what every poem of mine says,

And all my poems are different,

Because each thing that exists is a different way of saying this.

Sometimes I start looking at a stone.

I don’t start thinking about whether it exists.

I don’t get sidetracked, calling it my sister.

I like it for being a stone,

I like it because it feels nothing,

I like it because it’s not related to me in any way.

At other times I hear the wind blow,

And I feel that it was worth being born just to hear the wind

… blow.

I don’t know what people will think when they read this,

But I feel it must be right since I think it without any effort

Or any idea of what people who hear me will think,

Because I think it without thoughts,

Because I say it the way my words say it.

I was once called a materialist poet,

And it surprised me, for I didn’t think

I could be called anything.

I’m not even a poet: I see.

If what I write has any value, the value isn’t mine,

It belongs to my poems.

All this is absolutely independent of my will.

Fernando Pessoa [as Alberto Caeiro]

from A little Larger Than The Entire Universe

Penguin Classic, 1998

AI software clears high hurdles on IQ tests but still makes dumb mistakes

Matthew Hutson in Science:

Trained on billions of words from books, news articles, and Wikipedia, artificial intelligence (AI) language models can produce uncannily human prose. They can generate tweets, summarize emails, and translate dozens of languages. They can even write tolerable poetry. And like overachieving students, they quickly master the tests, called benchmarks, that computer scientists devise for them. That was Sam Bowman’s sobering experience when he and his colleagues created a tough new benchmark for language models called GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation). GLUE gives AI models the chance to train on data sets containing thousands of sentences and confronts them with nine tasks, such as deciding whether a test sentence is grammatical, assessing its sentiment, or judging whether one sentence logically entails another. After completing the tasks, each model is given an average score.

Trained on billions of words from books, news articles, and Wikipedia, artificial intelligence (AI) language models can produce uncannily human prose. They can generate tweets, summarize emails, and translate dozens of languages. They can even write tolerable poetry. And like overachieving students, they quickly master the tests, called benchmarks, that computer scientists devise for them. That was Sam Bowman’s sobering experience when he and his colleagues created a tough new benchmark for language models called GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation). GLUE gives AI models the chance to train on data sets containing thousands of sentences and confronts them with nine tasks, such as deciding whether a test sentence is grammatical, assessing its sentiment, or judging whether one sentence logically entails another. After completing the tasks, each model is given an average score.

At first, Bowman, a computer scientist at New York University, thought he had stumped the models. The best ones scored less than 70 out of 100 points (a D+). But in less than 1 year, new and better models were scoring close to 90, outperforming humans. “We were really surprised with the surge,” Bowman says. So in 2019 the researchers made the benchmark even harder, calling it SuperGLUE. Some of the tasks required the AI models to answer reading comprehension questions after digesting not just sentences, but paragraphs drawn from Wikipedia or news sites. Again, humans had an initial 20-point lead. “It wasn’t that shocking what happened next,” Bowman says. By early 2021, computers were again beating people.

More here.

Playing Hardball: Kenneth Roth on His Three Decades Leading Human Rights Watch

Jonathan Tepperman in The Octavian Report:

Last week, Ken Roth, who’s led Human Rights Watch for nearly 30 years, announced that he was stepping down. Over the course of his career, Roth, a former U.S. federal prosecutor, has had a profound impact on the organization and the cause he serves. What was once a modest outfit of some 60 people with a budget of $7 million is now a major global operation of 552 staffers operating in more than 100 countries and with a budget of close to $100 million. But Roth’s tenure hasn’t just been about organization-building or fundraising. In the course of his years with Human Rights Watch, he’s met with dozens of heads of state and worked in more than 50 countries. Under his management, the group shared the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for working to ban landmines; helped the UN establish the war crimes tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and then the International Criminal Court; and fought against the use of cluster munitions and child soldiers, among many issues. Along the way, as you’d expect, Roth has made many friends and supporters but also enemies; at various moments, he’s been accused of anti-Semitism (despite being Jewish), been attacked by Republican politicians in the United States, and has been denounced by a long list of autocratic governments, from China to Rwanda. I’ve known Roth for many years and was curious to get his reflections on a career spent fighting for justice, as well as the state of the world today and how it compares to 1993, when he was first named executive director of Human Rights Watch. We spoke about all this and more on Tuesday.

Last week, Ken Roth, who’s led Human Rights Watch for nearly 30 years, announced that he was stepping down. Over the course of his career, Roth, a former U.S. federal prosecutor, has had a profound impact on the organization and the cause he serves. What was once a modest outfit of some 60 people with a budget of $7 million is now a major global operation of 552 staffers operating in more than 100 countries and with a budget of close to $100 million. But Roth’s tenure hasn’t just been about organization-building or fundraising. In the course of his years with Human Rights Watch, he’s met with dozens of heads of state and worked in more than 50 countries. Under his management, the group shared the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for working to ban landmines; helped the UN establish the war crimes tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and then the International Criminal Court; and fought against the use of cluster munitions and child soldiers, among many issues. Along the way, as you’d expect, Roth has made many friends and supporters but also enemies; at various moments, he’s been accused of anti-Semitism (despite being Jewish), been attacked by Republican politicians in the United States, and has been denounced by a long list of autocratic governments, from China to Rwanda. I’ve known Roth for many years and was curious to get his reflections on a career spent fighting for justice, as well as the state of the world today and how it compares to 1993, when he was first named executive director of Human Rights Watch. We spoke about all this and more on Tuesday.

More here.

Where Do Space, Time and Gravity Come From?

Steven Strogatz talks to Sean Carroll at Quanta:

Strogatz (02:56): It’s very exciting to me to be talking with the master of emergent space-time. Really mind-boggling stuff, I enjoyed your book very much. I hope you can help us make some sense of these really thorny and fascinating issues in, I’d say, at the frontiers of physics today.

Why are you guys, you physicists, worrying so much about space and time again? I thought Einstein took care of that for us a long time ago. What’s really missing?

Carroll (03:21): Yeah, you know, we think of relativity, the birth of relativity in the early 20th century, as a giant revolution in physics. But it was nothing compared to the quantum revolution that happened a few years later.

More, including transcript, here.

Our Global Food System Was Already in Crisis, Russia’s War Will Make It Worse

Raj Patel in the Boston Review:

The first tank hadn’t yet rolled across the border before the U.S. oil industry was recycling calls to “drill, baby, drill.” Now it’s food’s turn. Together Russia and Ukraine accounted for just under 30 percent of global wheat exports in 2021. The price of wheat hit a record high this year at approximately $12.94 a bushel (it opened the year at $7.55). The Financial Times reports that the U.S. Farm Service Agency is thinking about loosening federal restrictions on land. Dig, baby, dig is a reactionary battle cry in waiting.

The first tank hadn’t yet rolled across the border before the U.S. oil industry was recycling calls to “drill, baby, drill.” Now it’s food’s turn. Together Russia and Ukraine accounted for just under 30 percent of global wheat exports in 2021. The price of wheat hit a record high this year at approximately $12.94 a bushel (it opened the year at $7.55). The Financial Times reports that the U.S. Farm Service Agency is thinking about loosening federal restrictions on land. Dig, baby, dig is a reactionary battle cry in waiting.

Higher food prices will lead to more people going hungry—and digging won’t solve the problem. The malnutrition caused by Russia’s war on Ukraine cannot be fixed by planting new wheat. The season is over for U.S. winter wheat. Farther north, only a small minority of Canadian farmers are bothering to plant more for the spring harvest. Even if farmers were to bend seasons, soil, and rain to their will, spring wheat won’t be ready for four months. The markets are already pricing in the shortfall. Croupiers at grain trading desks the world over are readying themselves for bumper bonuses amid the meager harvests.

More here.

How David C. Roy Builds Mesmerizing Kinetic Sculptures

Kazuo Hara’s Dedicated Lives

Markus Nornes at The Current:

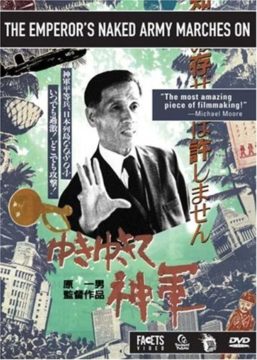

The notoriety of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987) always precedes it, yet the film never fails to evoke shock and wonder at its stunning improbability. The subject of this documentary is one of cinema’s greatest bullies. Both relentless and charismatic, Kenzo Okazaki was a veteran of the terrifying battles on Papua New Guinea at the end of World War II, and was clearly damaged by the experience. At the time of shooting, the radicality of the war’s violence was being erased from history by Japan’s right wing, and Okazaki was on a mission to push his audiences’ noses into the messiness. He tyrannically usurps the filmmakers, positioning them as mere witnesses to his project: visiting his old army buddies one by one to literally beat the truth out of them. Having witnessed or participated in crimes perpetrated against Japanese soldiers by their own officers, these men have a secret, and its revelation and memorialization on film is Okazaki’s mission.

The notoriety of The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987) always precedes it, yet the film never fails to evoke shock and wonder at its stunning improbability. The subject of this documentary is one of cinema’s greatest bullies. Both relentless and charismatic, Kenzo Okazaki was a veteran of the terrifying battles on Papua New Guinea at the end of World War II, and was clearly damaged by the experience. At the time of shooting, the radicality of the war’s violence was being erased from history by Japan’s right wing, and Okazaki was on a mission to push his audiences’ noses into the messiness. He tyrannically usurps the filmmakers, positioning them as mere witnesses to his project: visiting his old army buddies one by one to literally beat the truth out of them. Having witnessed or participated in crimes perpetrated against Japanese soldiers by their own officers, these men have a secret, and its revelation and memorialization on film is Okazaki’s mission.

This is one of those films that people always remember where, when, and how they watched. It made the career of its director, Kazuo Hara. To this day, anyone introducing him inevitably invokes Emperor’s Naked Army, even though his entire filmography makes for compelling viewing.

more here.

The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On

Circular Migration To And From The Caribbean

Colin Grant at Lapham’s Quarterly:

Today almost as many Caribbeans reside overseas than live at home. Outward and inward migration from and to the region provides an illuminating case study into the pattern and history of migration. Immigrant has become a dirty word, a term of abuse. But Caribbean pioneers have been, and continue to be, a great expeditionary force that keeps the world turning.

Today almost as many Caribbeans reside overseas than live at home. Outward and inward migration from and to the region provides an illuminating case study into the pattern and history of migration. Immigrant has become a dirty word, a term of abuse. But Caribbean pioneers have been, and continue to be, a great expeditionary force that keeps the world turning.

People have always been on the move, all the more when travel became easier. On one level, the world can be divided into those who leave their birthplace and those who remain. “To be born on a small island, a colonial backwater,” wrote Derek Walcott, “meant a precocious resignation to fate.” The only protest was to get away. When Ethlyn and my father, Bageye, left in 1959, they did so in the midst of what was coined “England fever.”

more here.

A crop of new books attempts to explain the allure of conspiracy theories

Trevor Quirk in Guernica:

For the millions who were enraged, disgusted, and shocked by the Capitol riots of January 6, the enduring object of skepticism has been not so much the lie that provoked the riots but the believers themselves. A year out, and book publishers confirmed this, releasing titles that addressed the question still addling public consciousness: How can people believe this shit? A minority of rioters at the Capitol had nefarious intentions rooted in authentic ideology, but most of them conveyed no purpose other than to announce to the world that they believed — specifically, that the 2020 election was hijacked through an international conspiracy — and that nothing could sway their confidence. This belief possessed them, not the other way around.

For the millions who were enraged, disgusted, and shocked by the Capitol riots of January 6, the enduring object of skepticism has been not so much the lie that provoked the riots but the believers themselves. A year out, and book publishers confirmed this, releasing titles that addressed the question still addling public consciousness: How can people believe this shit? A minority of rioters at the Capitol had nefarious intentions rooted in authentic ideology, but most of them conveyed no purpose other than to announce to the world that they believed — specifically, that the 2020 election was hijacked through an international conspiracy — and that nothing could sway their confidence. This belief possessed them, not the other way around.

At first, I’d found the riots both terrifying and darkly hilarious, but those sentiments were soon overwon by a strange exasperation that has persisted ever since. It’s a feeling that has robbed me of my capacity to laugh at conspiracy theories — QAnon, chemtrails, lizardmen, whatever — and the people who espouse them. My exasperation is for lack of an explanation.

More here.

Will new vaccines be better at fighting coronavirus variants?

Vaibhav Upadhyay and Krishna Mallela in The Conversation:

A major reason why new vaccines are important – and why the world is still dealing with COVID-19 – is the continued emergence of new variants. Most of the differences between variants are changes in the spike protein, which is on the surface of the virus and helps it enter and infect cells.

A major reason why new vaccines are important – and why the world is still dealing with COVID-19 – is the continued emergence of new variants. Most of the differences between variants are changes in the spike protein, which is on the surface of the virus and helps it enter and infect cells.

Some of these small changes in the spike protein have allowed the coronavirus to infect human cells more efficiently. These changes have also made it so that previous vaccinations or infections with COVID-19 provide less protection against the new variants. Updated or new vaccines could be better at detecting these different spike proteins and better at protecting against new variants.

So far, 38 vaccines have been approved around the world, and the U.S. has approved three of those. There are currently 195 vaccine candidates at different stages of development worldwide, out of which 41 are in clinical trials in U.S. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 can be broadly divided into four classes: whole virus, viral vector, protein-based and nucleic acid-based vaccines.

More here.

Some Lessons from the Sorry History of Campus Speech Codes

Greg Lukianoff and Talia Barnes in Persuasion:

Concern about the proliferation of hate speech motivates many who oppose the recent acquisition of Twitter by billionaire Elon Musk, who says he plans to turn the heavily moderated platform into a bastion for free speech. Sources ranging from writers at major news publications to CEOs have voiced fears that free-speech-friendly policies will make the platform a haven for “totally lawless hate, bigotry, and misogyny,” as actress Jameela Jamil put it in her farewell-to-Twitter tweet.

Concern about the proliferation of hate speech motivates many who oppose the recent acquisition of Twitter by billionaire Elon Musk, who says he plans to turn the heavily moderated platform into a bastion for free speech. Sources ranging from writers at major news publications to CEOs have voiced fears that free-speech-friendly policies will make the platform a haven for “totally lawless hate, bigotry, and misogyny,” as actress Jameela Jamil put it in her farewell-to-Twitter tweet.

But those who take for granted that hate speech should be policed on Twitter would do well to learn the history of attempts to police hate speech on campuses in the United States. Some readers may be surprised to learn that American universities have attempted to regulate hate speech for four decades now: This real-world experiment has shown how subjective and nebulous restrictions chill speech in often-surprising ways.

More here.