Alexander Larman in The Critic:

If Sir Kingsley Amis was still alive today, on the occasion of his centenary — an event that would owe a quite remarkable amount to medical science, and might, given the context of this particular weekend, even be seen as a second Resurrection narrative — he might be amused by the way that he has been treated by posterity. I’ve written about the decline in Kingers’ fortunes, justified or not, for the May issue of The Critic, but one area that I was only able to touch on in the most passing of fashions was one that many Amis aficionados prefer not to dwell on. Yes — oh dear yes — Kingsley Amis wrote poetry. Many may have wished that it were not so.

If Sir Kingsley Amis was still alive today, on the occasion of his centenary — an event that would owe a quite remarkable amount to medical science, and might, given the context of this particular weekend, even be seen as a second Resurrection narrative — he might be amused by the way that he has been treated by posterity. I’ve written about the decline in Kingers’ fortunes, justified or not, for the May issue of The Critic, but one area that I was only able to touch on in the most passing of fashions was one that many Amis aficionados prefer not to dwell on. Yes — oh dear yes — Kingsley Amis wrote poetry. Many may have wished that it were not so.

This does one of the twentieth century’s most brilliant writers a disservice. One of the oft-repeated ironies of his epochal friendship with Philip Larkin is that, for a fair amount of their early lives, each man saw himself in the opposite sphere to the one in which he ended up excelling: Larkin wished to be a novelist, Amis a poet.

More here.

Well Rick B. from the United States, it seems that you did not like the Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s newest film The Worst Person in The World very much. Your Amazon review is quite short, and pretty rough. You gave it one star. The title of your review is “tedious, annoying people talking too much.” And then you followed that up with two words and an exclamation mark: “It sucks!”

Well Rick B. from the United States, it seems that you did not like the Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s newest film The Worst Person in The World very much. Your Amazon review is quite short, and pretty rough. You gave it one star. The title of your review is “tedious, annoying people talking too much.” And then you followed that up with two words and an exclamation mark: “It sucks!” When the mathematicians

When the mathematicians  Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the next technological revolution, a breakthrough that poses both great risks and great rewards for human rights. Our ability to mitigate AI’s risks will depend not on its technical features, but on how and why those features are used. A hammer can build a house or break a skull — the impact of any tool depends on who wields it, their intentions behind its use, and what constraints, if any, have been built around the tool’s use.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the next technological revolution, a breakthrough that poses both great risks and great rewards for human rights. Our ability to mitigate AI’s risks will depend not on its technical features, but on how and why those features are used. A hammer can build a house or break a skull — the impact of any tool depends on who wields it, their intentions behind its use, and what constraints, if any, have been built around the tool’s use. Creativity is an essential element of the human condition. Yet unlike other elements of our humanity, there’s a perception that creativity seems to leave us as we age. Children, wrapped up in their imaginary play worlds and projects, are notoriously unhindered in their creativity. But adults are far less adept at conjuring the fantastical and bizarre imagination that their childhood selves had easy access to. Many adults long for those playful youthful days, when conjuring up a grand scene, on paper or on the playground, was as natural as breathing.

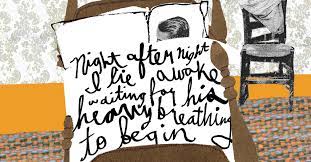

Creativity is an essential element of the human condition. Yet unlike other elements of our humanity, there’s a perception that creativity seems to leave us as we age. Children, wrapped up in their imaginary play worlds and projects, are notoriously unhindered in their creativity. But adults are far less adept at conjuring the fantastical and bizarre imagination that their childhood selves had easy access to. Many adults long for those playful youthful days, when conjuring up a grand scene, on paper or on the playground, was as natural as breathing. Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was once the most famous poet in America. Her collections sold tens of thousands of copies, and her readings filled theaters from New York to Texas. She was the female voice of the Jazz Age, the New Woman incarnate whose passionate and iconoclastic verse earned her a devoted following. Her 1920 poem “First Fig” became an anthem for a generation tired of Victorian mores:

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was once the most famous poet in America. Her collections sold tens of thousands of copies, and her readings filled theaters from New York to Texas. She was the female voice of the Jazz Age, the New Woman incarnate whose passionate and iconoclastic verse earned her a devoted following. Her 1920 poem “First Fig” became an anthem for a generation tired of Victorian mores: