Cressida Leyshon in The New Yorker:

This week’s story, “The Face in the Mirror,” is about a man named Anders who wakes one morning and discovers that his skin is no longer white. He’s now a dark man. Why did this scenario first come to you?

I spent most of the nineteen-seventies and most of the nineteen-nineties in America. I lived in liberal enclaves, attended prestigious schools, had a well-paying job. Then, after 9/11, I experienced a profound sense of loss. I was constantly stopped at immigration, held for hours at the airport, once pulled off a flight that was already on the tarmac. I had become an object of suspicion, even fear. I had lost something. And, over the years, I began to realize that I had lost my partial whiteness. Not that I had been white before: I am brown-skinned, with a Muslim name. But I had been able to partake in many of the benefits of whiteness. And I had been complicit in that system. Losing this forced me to consider things afresh. And over the next couple of decades that experience was the grain of debris in my mind’s oyster that this work began to accrue around.

More here.

Twitter is toxic, suggests autocomplete; Twitter is an echo chamber, or at best a waste of time. Twitter is a hotbed of political factionalism. Twitter can be a frightening place for people who are harassed or threatened, and it may become more so when a recently announced takeover is complete. The bullying and misinformation and political threat are all real, and they’ve been central to recent discussions about the takeover. But Twitter is a big place, and some of us are there mainly for things we love. Birds, for example, and poems.

Twitter is toxic, suggests autocomplete; Twitter is an echo chamber, or at best a waste of time. Twitter is a hotbed of political factionalism. Twitter can be a frightening place for people who are harassed or threatened, and it may become more so when a recently announced takeover is complete. The bullying and misinformation and political threat are all real, and they’ve been central to recent discussions about the takeover. But Twitter is a big place, and some of us are there mainly for things we love. Birds, for example, and poems.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who find basements scary and those who find attics scary. I suppose there might be some folks (bless their hearts) who are disturbed by both, like those ethereal creatures with one blue eye and one brown. I refuse to countenance the idea of people who have no feelings of unease in either space. To be that well-adjusted, that free from inchoate fear, that grounded in the solid objects of reality—I draw back in horror at the thought. We will leave these hale and pragmatic types to their smoothies and their 401Ks and godspeed to them.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who find basements scary and those who find attics scary. I suppose there might be some folks (bless their hearts) who are disturbed by both, like those ethereal creatures with one blue eye and one brown. I refuse to countenance the idea of people who have no feelings of unease in either space. To be that well-adjusted, that free from inchoate fear, that grounded in the solid objects of reality—I draw back in horror at the thought. We will leave these hale and pragmatic types to their smoothies and their 401Ks and godspeed to them.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy.

I find Sue Hubbard’s writings to be an invitation to feel sorrowful. And therefore a beckoning towards a search for beauty, an attempt at forgiveness and redemption and reckoning; a belief in the possibility of joy. June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai.

June 4 early morning we took a taxi from Friendship Hotel to the Beijing airport, oblivious of the dreadful happenings in Tiananmen Square the previous night. I remember the taxi driver in his almost non-existent English tried to tell us that ‘something’ (he was not sure what) had happened in the night in the Square, traffic was not allowed to go in that direction. By the time we reached Shanghai, our hosts who came to receive us knew. Of course, they could not know it from radio or TV, as there was a news blackout. These were days before internet, but cross-country fax messages were still active. Beijing to Shanghai messages were blocked, but people in Beijing were sending fax messages to their friends and relatives in Los Angeles, and the latter were sending messages to Shanghai. ROBERT

ROBERT The fact that wings are not always a good thing is demonstrated by those animals whose ancestors used to have wings but who have given them up.

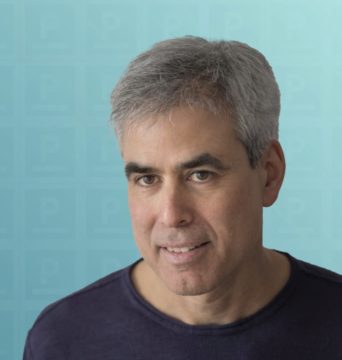

The fact that wings are not always a good thing is demonstrated by those animals whose ancestors used to have wings but who have given them up. Jonathan Haidt: The piece is the culmination of my eight-year struggle to understand what the hell happened. I’ve been a professor since 1995. I love being a professor, I love universities. I just felt like this is the greatest job on Earth. I got a glimpse, as a philosophy major, of Plato’s Academy—sitting under the olive trees talking about ideas. And then all of a sudden, from out of nowhere in 2014, things got weird. They got aggressive and they got frightening. This game has been going on for thousands of years, in which one person serves something, the other person hits it back—around 2014, intimidation came in. There was a new element, which was that if you say something, people won’t argue why you’re wrong, they’ll slam you as a bad person. On the left, they’ll call you a racist; on the right, they’ll call you a traitor. But something changed on campus.

Jonathan Haidt: The piece is the culmination of my eight-year struggle to understand what the hell happened. I’ve been a professor since 1995. I love being a professor, I love universities. I just felt like this is the greatest job on Earth. I got a glimpse, as a philosophy major, of Plato’s Academy—sitting under the olive trees talking about ideas. And then all of a sudden, from out of nowhere in 2014, things got weird. They got aggressive and they got frightening. This game has been going on for thousands of years, in which one person serves something, the other person hits it back—around 2014, intimidation came in. There was a new element, which was that if you say something, people won’t argue why you’re wrong, they’ll slam you as a bad person. On the left, they’ll call you a racist; on the right, they’ll call you a traitor. But something changed on campus. Europe is geographically much closer to Africa than America. Northern Africa has been part of the Eurasian culture since Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, over two millennia ago.

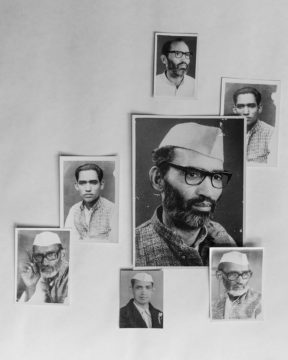

Europe is geographically much closer to Africa than America. Northern Africa has been part of the Eurasian culture since Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, over two millennia ago. There is a particular collage in Indian photographer Devashish Gaur’s project This Is The Closest We Will Get that stands out in its cut-and-paste simplicity. Entitled Me and Dad, it’s a portrait, black and white, cropped at the shoulders, but most importantly, it depicts two men instead of one. The sitter of the original photograph—an archival one that’s been collaged over—wears a checkered suit and his hair is neatly swept to the side. It feels formal, perhaps a little dated even. Meanwhile, slices of a second face, arranged over this sitter, belong to his son—the photographer, Gaur himself. And their features, the contours and outlines of their faces, do seem to blend quite remarkably. Father and boy, artist and sitter, portrait and self-portrait, entwined.

There is a particular collage in Indian photographer Devashish Gaur’s project This Is The Closest We Will Get that stands out in its cut-and-paste simplicity. Entitled Me and Dad, it’s a portrait, black and white, cropped at the shoulders, but most importantly, it depicts two men instead of one. The sitter of the original photograph—an archival one that’s been collaged over—wears a checkered suit and his hair is neatly swept to the side. It feels formal, perhaps a little dated even. Meanwhile, slices of a second face, arranged over this sitter, belong to his son—the photographer, Gaur himself. And their features, the contours and outlines of their faces, do seem to blend quite remarkably. Father and boy, artist and sitter, portrait and self-portrait, entwined. As a mother of six and a Mormon, I have a good understanding of arguments surrounding abortion, religious and otherwise. When I hear men discussing women’s reproductive rights, I’m often left with the thought that they have zero interest in stopping abortion. If you want to prevent abortion, you need to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Men seem unable (or unwilling) to admit that they cause 100% of them. I realize that’s a bold statement. You’re likely thinking, “Wait. It takes two to tango!” While I fully agree with you in the case of intentional pregnancies, I argue that all unwanted pregnancies are caused by the irresponsible ejaculations of men. All of them.

As a mother of six and a Mormon, I have a good understanding of arguments surrounding abortion, religious and otherwise. When I hear men discussing women’s reproductive rights, I’m often left with the thought that they have zero interest in stopping abortion. If you want to prevent abortion, you need to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Men seem unable (or unwilling) to admit that they cause 100% of them. I realize that’s a bold statement. You’re likely thinking, “Wait. It takes two to tango!” While I fully agree with you in the case of intentional pregnancies, I argue that all unwanted pregnancies are caused by the irresponsible ejaculations of men. All of them.