Carolyn Wilke in Smithsonian:

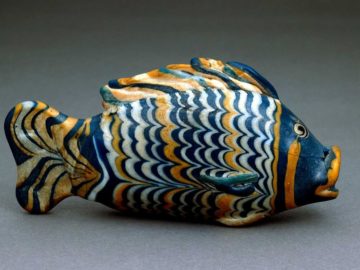

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a decorative writing palette and two blue-hued headrests made of solid glass that may once have supported the head of sleeping royals. His funerary mask sports blue glass inlays that alternate with gold to frame the king’s face.

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a decorative writing palette and two blue-hued headrests made of solid glass that may once have supported the head of sleeping royals. His funerary mask sports blue glass inlays that alternate with gold to frame the king’s face.

In a world filled with the buff, brown and sand hues of more utilitarian Late Bronze Age materials, glass — saturated with blue, purple, turquoise, yellow, red and white — would have afforded the most striking colors other than gemstones, says Andrew Shortland, an archaeological scientist at Cranfield University in Shrivenham, England. In a hierarchy of materials, glass would have sat slightly beneath silver and gold and would have been valued as much as precious stones were. But many questions remain about the prized material. Where was glass first fashioned? How was it worked and colored, and passed around the ancient world? Though much is still mysterious, in the last few decades materials science techniques and a reanalysis of artifacts excavated in the past have begun to fill in details.

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent.

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent. In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister

In March 2020, Boris Johnson, pale and exhausted, self-isolating in his flat on Downing Street, released a video of himself – that he had taken himself – reassuring Britons that they would get through the pandemic, together. “One thing I think the coronavirus crisis has already proved is that there really is such a thing as society,” the prime minister  I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after

I thought often about something the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders said, after  Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper.

Why have I come so far on a literary pilgrimage? I want to be unafraid to move in the world again. But what do I expect from a visit to the three-quarters-Canadian, one-quarter-American poet Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood home? “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” Bishop asks in her marvelous poem “Questions of Travel.” Am I, like her, dreaming my dream and having it too? Is it a lack of imagination that brings me to Great Village? “Shouldn’t you have stayed at home and thought of here?” I can hear her asking. I wish my friend Rachel were here as planned. She would know the answers to these questions. She is receiving a new treatment and isn’t herself. In 1979, on the weekend that Bishop died, Rachel knocked on her door at 437 Lewis Wharf—Rachel still lives upstairs—because she knew Bishop wasn’t feeling well, and offered to bring her some milk and eggs from the local market, but Bishop demurred. A couple of days later, Bishop’s friend and companion Alice Methfessel phoned to say that Elizabeth had died and that she didn’t want Rachel to be shocked to read about it in the newspaper. Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy.

Richard Rorty (1931–2007) was the philosopher’s anti-philosopher. His professional credentials were impeccable: an influential anthology (The Linguistic Turn, 1967); a game-changing book (Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, 1979); another, only slightly less original book (Consequences of Pragmatism, 1982); a best-selling (for a philosopher) collection of literary/philosophical/political lectures and essays (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 1989); four volumes of Collected Papers from the venerable Cambridge University Press; president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association (1979). He seemed to be speaking at every humanities conference in the 1980s and 1990s, about postmodernism, critical theory, deconstruction, and the past, present, and future (if any) of philosophy. Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born.

Tiny is pregnant, but not as we know it: she is expecting an “owl-baby”, the result of a secret tryst with a female “owl-lover”. “This baby will never learn to speak, or love, or look after itself”, Tiny knows. Her husband, an intellectual property lawyer, thinks her panic is just pregnancy jitters, and that she’s carrying his child. Even when he finds a disembowelled possum on the path and his “well fed” wife sitting in the dark (“It didn’t feel dark to me. I see everything”), he doesn’t believe. Then the baby is born. In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years.

In her preface to the 2021 paperback edition of Thanksgiving, marking the 400th anniversary of the American Thanksgiving, Melanie Kirkpatrick expresses her concern for the continued celebration of the venerable holiday. “Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving.” (x) Her use of the word “heroes” clearly places her on a particular side in this installment of the culture wars, but her worry is legitimate. Thanksgiving could fall, condemned as a symbol, a relic of White supremacy, simultaneously celebrating and masking genocide, colonialism, and racism, just as Columbus Day has died an ignoble (and for many a deserved) death across a good swath of the United States. The fact that Kirkpatrick does not touch upon this at all in the introduction to the 2016 edition of her book shows just how decisive (Kirkpatrick would probably say destructive) a force cancel culture has become in a mere five years. Today the reduction procedure, known as the Laporta algorithm, has become the main tool for generating precise predictions about particle behavior. “It’s ubiquitous,” said

Today the reduction procedure, known as the Laporta algorithm, has become the main tool for generating precise predictions about particle behavior. “It’s ubiquitous,” said  The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) fell far short of what is needed for a safe planet, owing mainly to the same lack of trust that has burdened global climate negotiations for almost three decades. Developing countries regard climate change as a crisis caused largely by the rich countries, which they also view as shirking their historical and ongoing responsibility for the crisis. Worried that they will be left paying the bills, many key developing countries, such as India, don’t much care to negotiate or strategize.

The United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) fell far short of what is needed for a safe planet, owing mainly to the same lack of trust that has burdened global climate negotiations for almost three decades. Developing countries regard climate change as a crisis caused largely by the rich countries, which they also view as shirking their historical and ongoing responsibility for the crisis. Worried that they will be left paying the bills, many key developing countries, such as India, don’t much care to negotiate or strategize. My last pandemic Thanksgiving dinner began in a jet black convertible-turned-restaurant booth where I watched as a teenaged pizzamaker took a break from scattering toppings on my 18-inch Supreme pie to take a hit and turn up “Heartbreakin’ Man” by My Morning Jacket. Spinelli’s Pizzeria in Louisville’s Highland neighborhood possesses a kind of curated grime. It’s covered in graffiti-style art (which is unsurprising because its staff is often a rotation of local taggers) and is packed with muscle car and pop culture ephemera, including a

My last pandemic Thanksgiving dinner began in a jet black convertible-turned-restaurant booth where I watched as a teenaged pizzamaker took a break from scattering toppings on my 18-inch Supreme pie to take a hit and turn up “Heartbreakin’ Man” by My Morning Jacket. Spinelli’s Pizzeria in Louisville’s Highland neighborhood possesses a kind of curated grime. It’s covered in graffiti-style art (which is unsurprising because its staff is often a rotation of local taggers) and is packed with muscle car and pop culture ephemera, including a  The

The  A.S. Byatt’s reputation as a master of the long form has been crystallized by Possession, a novel of depth, breadth and heft; the “Frederica Quartet,” a prose tapestry of post-war England; and The Children’s Book, a many-chambered country house of a narrative. Her new collection, Medusa’s Ankles, showcases Byatt’s gifts as a master of the short story. To my mind, she belongs in that select club of writers whose members include Dickens, John Cheever, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Elizabeth Bowen, and who achieve virtuosity in both short- and long-form fiction.

A.S. Byatt’s reputation as a master of the long form has been crystallized by Possession, a novel of depth, breadth and heft; the “Frederica Quartet,” a prose tapestry of post-war England; and The Children’s Book, a many-chambered country house of a narrative. Her new collection, Medusa’s Ankles, showcases Byatt’s gifts as a master of the short story. To my mind, she belongs in that select club of writers whose members include Dickens, John Cheever, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Elizabeth Bowen, and who achieve virtuosity in both short- and long-form fiction. Metaculus predicts

Metaculus predicts Superhero movies offer plenty of drama: big personalities, colorful explosions, the fate of the world hanging on the contest between good and evil. Thrilling as they may be, these movies don’t provide much practical guidance about saving the real world, where our problems demand more grappling with ambiguity than derring-do. Yet you can see the influence of superhero theatrics in public discourse about the culture wars. On Twitter and in podcasts, everything now seems to be an epochal struggle between two factions, the “Wokeists” and the “anti-Wokeists,” whose battles over social justice will doom or save us all.

Superhero movies offer plenty of drama: big personalities, colorful explosions, the fate of the world hanging on the contest between good and evil. Thrilling as they may be, these movies don’t provide much practical guidance about saving the real world, where our problems demand more grappling with ambiguity than derring-do. Yet you can see the influence of superhero theatrics in public discourse about the culture wars. On Twitter and in podcasts, everything now seems to be an epochal struggle between two factions, the “Wokeists” and the “anti-Wokeists,” whose battles over social justice will doom or save us all.