Month: November 2021

Getting Beyond The Transportation Debate

Addison Del Mastro at The New Atlantis:

Much of this progressive ire is directed at the presence of cars in cities. It resists how cities are shaped to suit the needs and preferences of drivers. But the attitude easily extends to sneering at rural or suburban life, especially when it seems to bleed over into cities. Consider the broad dislike of SUVs. Urbanists associate the increasing prevalence of SUVs in New York City with a rising numbers of car crashes and fatalities — and for better or worse, SUVs are also today’s standard suburban family vehicle. But instead of focusing on the broader system of car dependence, some of the most vocal urbanist car critics attack the lifestyle choices of individual motorists or car ownership generally.

Much of this progressive ire is directed at the presence of cars in cities. It resists how cities are shaped to suit the needs and preferences of drivers. But the attitude easily extends to sneering at rural or suburban life, especially when it seems to bleed over into cities. Consider the broad dislike of SUVs. Urbanists associate the increasing prevalence of SUVs in New York City with a rising numbers of car crashes and fatalities — and for better or worse, SUVs are also today’s standard suburban family vehicle. But instead of focusing on the broader system of car dependence, some of the most vocal urbanist car critics attack the lifestyle choices of individual motorists or car ownership generally.

Underlying the conflict between cars and transit, suburbs and cities, we might imagine a shared vision of how mobility is crucial to economic stability and flourishing communities — a vision that ought to be appealing to both liberals and conservatives.

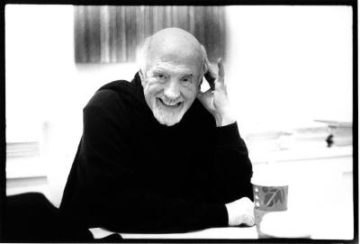

On Sylvère Lotringer (1938–2021)

Marco Roth at n+1:

Sylvère’s way of creating accidents or chance was like this: He’d come in to the classroom of about five to ten students, depending on the day, and begin thinking aloud about literature, art, and philosophy—in French or occasionally heavily accented English—in a way that I only understood, at some point during my second or third Sylvère semester, was intended to “disorganize” us, his students, regardless of our level. If we asked him to explain “structuralism,” he might lecture on Saussure and Barthes for a while, but then go off into Nietzsche, the schizophrenic writings of Judge Daniel Paul Schreber, and onto Deleuze, thus making clear the limitations of any rage for ordering things. Sylvère encouraged or provoked everyone to excess. Even the French graduate student who gave a seemingly flawless presentation on the idea of “la grève” in Mallarmé and Rimbaud, and who once accused me of working for the police when I asked him how long he was staying at Columbia—a true disciple if ever there was one—Sylvère blew up his presentation, too.

Sylvère’s way of creating accidents or chance was like this: He’d come in to the classroom of about five to ten students, depending on the day, and begin thinking aloud about literature, art, and philosophy—in French or occasionally heavily accented English—in a way that I only understood, at some point during my second or third Sylvère semester, was intended to “disorganize” us, his students, regardless of our level. If we asked him to explain “structuralism,” he might lecture on Saussure and Barthes for a while, but then go off into Nietzsche, the schizophrenic writings of Judge Daniel Paul Schreber, and onto Deleuze, thus making clear the limitations of any rage for ordering things. Sylvère encouraged or provoked everyone to excess. Even the French graduate student who gave a seemingly flawless presentation on the idea of “la grève” in Mallarmé and Rimbaud, and who once accused me of working for the police when I asked him how long he was staying at Columbia—a true disciple if ever there was one—Sylvère blew up his presentation, too.

more here.

Sylvère Lotringer on Antonin Artaud

Wednesday Poem

Second Drink

………… For my grandfather, Michael Giovio, 1920-1997

………… On my pillow bit by bit waking,

………… suddenly I hear a cicada cry—

………… at that moment I know I’ve not died,

………… though past days are like a former existence,

………… I want to go to the window, listen closer,

………… but even with a cane I cant manage.

………… Before long like you I’ll shed my shell

………… and drink again the clear brightness of the dew.

………… ..—Xin Oiji, “Start of Autumn: “Hearing a Cicada While Sick in Bed”

On your pillow, bit by bit waking,

….. dreams of playground slides, highways, swatches of sky

all scatter into the fume of your first breath, waking.

Bit by bit, on your pillow, you wake

and suddenly you hear a cicada cry

….. from its flaky tomb. Caked in green, a fresh buzz breaking

the silence of an eight o’clock light, a clear cicada cry.

Suddenly you hear a cicada cry,

and at that moment, you know you have not died.

….. Now, an armada of cicadas, in apocalyptic quaking,

soars from the trees that have not died.

Neither, at that moment, have you.

though past days are like a former existence,

….. cast in a tomb, gilded in aching

like the words of a song that only in memory exists.

Future days, too, are like a former existence.

You want to go to the window, listen closer

….. to the cicada’s rise, their resurrection, they’re remaking,

but your legs cannot bring you closer.

You want to go to the window, listen closer,

but even with a cane, you can’t manage.

….. Never in your daughter’s dreams are your legs forsaken—

they’re your wings, your wheels, your dream’s imagining—

but even with a cane, you can’t manage.

Before long, like the cicada, you’ll shed your shell—

….. your apocalyptic limbs regaining, reshaping—

stronger now than used to be. Strong like the cicada, you’ll shed your shell.

Before long, like the cicada, you’ll shed your shell

and drink the clear brightness of the dew.

….. You’ll drink again the clear brightness of the dew,

and bit by bit, you will wake.

by Lauren Marie Schmidt

from Filthy Labors

Curbstone Books, 2017

What’s it like to be a bird?

Dominic Ziegler in More Intelligent Life:

There is a problem in getting up close to birds in order to celebrate them. Warm-blooded, they support striking levels of energy and movement. They are social, active and dynamic – most of them fly, though there are significant species of flightless birds. Birds rarely stand still, especially near humans. That’s why the pioneering illustrators of the 19th century sought dead specimens to bring into the studio to paint. John James Audubon’s 1838 engraving of a shocking-pink, double-bent flamingo is one of America’s best-known images, but his career was as much about slaughtering birds – and encouraging a network of associates to do the same – as it was about illustrating them. (He was also a slave owner; some environmental groups are now dropping his name.)

There is a problem in getting up close to birds in order to celebrate them. Warm-blooded, they support striking levels of energy and movement. They are social, active and dynamic – most of them fly, though there are significant species of flightless birds. Birds rarely stand still, especially near humans. That’s why the pioneering illustrators of the 19th century sought dead specimens to bring into the studio to paint. John James Audubon’s 1838 engraving of a shocking-pink, double-bent flamingo is one of America’s best-known images, but his career was as much about slaughtering birds – and encouraging a network of associates to do the same – as it was about illustrating them. (He was also a slave owner; some environmental groups are now dropping his name.)

In contrast to the Victorians’ skins and taxidermy specimens – often much-travelled, moth-eaten and peppered with lead shot – a new book by Tim Flach shows birds full of life and vigour. In “Birds”, he could not draw them closer. Flach’s photographs represent a kind of end-station or apotheosis of humans’ age-old and passionate quest to capture and possess the beauty of birds. Hyperreal and drenched in colour, the studio portraits of his avian subjects put him in a long and inspired tradition of artist-ornithologists. Photography, says Flach, may allow the viewer a deeper experience of birds than observing them from a distance, in motion. The image, he writes, “invites us to examine and contemplate the bending of a feather caught in flight, the minute details of the vanes and barbules of plumage, the frozen moments of torpedo-like diving penguins, the painterly reflections of flamingos wading.” Few figurative depictions of birds have done anything quite like this.

More here.

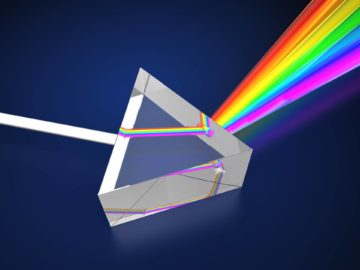

Spectrometry and Spectroscopy: What’s the difference?

From ATA Scientific:

Scientific terms are often used interchangeably, and scientifically-accepted descriptions are constantly being refined and reinterpreted, which can lead to errors in scientific understanding. While such errors can’t be completely eliminated, they can be reduced by making ourselves aware of them, better understanding the terminology, and using thoughtful and careful scientific methods. This is certainly true when it comes to understanding spectroscopy and spectrometry which, despite being similar, aren’t the same thing. With this in mind, let’s take a deeper look at these terms.

Scientific terms are often used interchangeably, and scientifically-accepted descriptions are constantly being refined and reinterpreted, which can lead to errors in scientific understanding. While such errors can’t be completely eliminated, they can be reduced by making ourselves aware of them, better understanding the terminology, and using thoughtful and careful scientific methods. This is certainly true when it comes to understanding spectroscopy and spectrometry which, despite being similar, aren’t the same thing. With this in mind, let’s take a deeper look at these terms.

Spectroscopy is the study of the absorption and emission of light and other radiation by matter. It involves the splitting of light (or more precisely electromagnetic radiation) into its constituent wavelengths (a spectrum), which is done in much the same way as a prism splits light into a rainbow of colours. In fact, old style spectroscopy was carried out using a prism and photographic plates. Modern spectroscopy uses diffraction grating to disperse light, which is then projected onto CCDs (charge-coupled devices), similar to those used in digital cameras. The 2D spectra are easily extracted from this digital format and manipulated to produce 1D spectra that contain an impressive amount of useful data.

More here.

Whose Anthropocene?

Mark Bould in the Boston Review:

Imagine a world haunted not just by the dead, but by the specter of death. Drawn ever closer by the already locked-in consequences of our actions and inaction. Its domain extended by endless escalating catastrophe.

Imagine a world haunted not just by the dead, but by the specter of death. Drawn ever closer by the already locked-in consequences of our actions and inaction. Its domain extended by endless escalating catastrophe.

Imagine a future of foreclosed possibilities.

Haunted by all the worlds that were, and all the worlds that could have been.

Then imagine—as Amitav Ghosh suggests in The Great Derangement (2016), the most widely read and highly regarded book on literature and climate change—that somewhere in the middle of all this, in a future in which “sea-level rise has swallowed the Sunderbans and made cities like Kolkata, New York, and Bangkok uninhabitable,” there are still museums and libraries and bookstores. Picture its inhabitants, urgently examining “the art and literature of our time . . . for traces and portents” of the upheavals that made their “substantially altered” world.

And “when they fail to find them,” Ghosh asks, “what should they—what can they—do other than to conclude that ours was a time when most forms of art and literature were drawn into the modes of concealment that prevented people from recognizing the realities of their plight?”

This is, of course, nonsense.

More here.

Why Health-Care Workers Are Quitting In Droves

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

Since COVID-19 first pummeled the U.S., Americans have been told to flatten the curve lest hospitals be overwhelmed. But hospitals have been overwhelmed. The nation has avoided the most apocalyptic scenarios, such as ventilators running out by the thousands, but it’s still sleepwalked into repeated surges that have overrun the capacity of many hospitals, killed more than 762,000 people, and traumatized countless health-care workers. “It’s like it takes a piece of you every time you walk in,” says Ashley Harlow, a Virginia-based nurse practitioner who left her ICU after watching her grandmother Nellie die there in December. She and others have gotten through the surges on adrenaline and camaraderie, only to realize, once the ICUs are empty, that so too are they.

Since COVID-19 first pummeled the U.S., Americans have been told to flatten the curve lest hospitals be overwhelmed. But hospitals have been overwhelmed. The nation has avoided the most apocalyptic scenarios, such as ventilators running out by the thousands, but it’s still sleepwalked into repeated surges that have overrun the capacity of many hospitals, killed more than 762,000 people, and traumatized countless health-care workers. “It’s like it takes a piece of you every time you walk in,” says Ashley Harlow, a Virginia-based nurse practitioner who left her ICU after watching her grandmother Nellie die there in December. She and others have gotten through the surges on adrenaline and camaraderie, only to realize, once the ICUs are empty, that so too are they.

Some health-care workers have lost their jobs during the pandemic, while others have been forced to leave because they’ve contracted long COVID and can no longer work. But many choose to leave, including “people whom I thought would nurse patients until the day they died,” Amanda Bettencourt, the president-elect of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, told me. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that the health-care sector has lost nearly half a million workers since February 2020.

More here.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez & Noam Chomsky: The Way Forward

Scientific American Goes Woke

Michael Shermer at his Substack Newsletter, Skeptic:

In April of 2001 I began my monthly Skeptic column at Scientific American, the longest continuously published magazine in the country dating back to 1845. With Stephen Jay Gould as my role model (and subsequent friend), it was my dream to match his 300 consecutive columns that he achieved at Natural History magazine, which would have taken me to April, 2026. Alas, my streak ended in January of 2019 after a run of 214 essays.

In April of 2001 I began my monthly Skeptic column at Scientific American, the longest continuously published magazine in the country dating back to 1845. With Stephen Jay Gould as my role model (and subsequent friend), it was my dream to match his 300 consecutive columns that he achieved at Natural History magazine, which would have taken me to April, 2026. Alas, my streak ended in January of 2019 after a run of 214 essays.

Since then, I have received many queries about why my column ended and, more generally, about what has happened over at Scientific American, which historically focused primarily on science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM), but now appears to be turning to social justice issues. There is, for example, the August 12, 2021 article on how “Modern Mathematics Confronts its White Patriarchal Past,” which asserts prima facie that the reason there are so few women and blacks in academic mathematics is because of misogyny and racism.

More here.

The Madness Of Renaissance Art

Dave Hickey Dies At 82

Alex Greenberger at ARTnews:

The Invisible Dragon exemplifies Hickey’s sensibility. It mounts an argument that beauty still mattered at a time when it was viewed as being anathema to relevant art-making, and it does so elegantly and seemingly effortlessly. In one essay, he compares Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexually explicit photography of queer subcultures to Caravaggio’s religious paintings. Using language indebted to art theory of the postwar era, he muses on sleek Mapplethorpe pictures that had been the subject of a culture war in the early ’90s, writing that they “seem so obviously to have come from someplace else, down by the piers, and to have brought with them, into the world of ice-white walls, the aura of knowing smiles, bad habits, rough language, and smoky, crowded rooms with raw brick walls, sawhorse bars and hand-lettered signs on the wall. They may be legitimate, but like my second cousins, Tim and Duane, they are far from respectable, even now.” Such a statement came alongside an honest disclosure: he had first come across these works in a coke dealer’s penthouse.

The Invisible Dragon exemplifies Hickey’s sensibility. It mounts an argument that beauty still mattered at a time when it was viewed as being anathema to relevant art-making, and it does so elegantly and seemingly effortlessly. In one essay, he compares Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexually explicit photography of queer subcultures to Caravaggio’s religious paintings. Using language indebted to art theory of the postwar era, he muses on sleek Mapplethorpe pictures that had been the subject of a culture war in the early ’90s, writing that they “seem so obviously to have come from someplace else, down by the piers, and to have brought with them, into the world of ice-white walls, the aura of knowing smiles, bad habits, rough language, and smoky, crowded rooms with raw brick walls, sawhorse bars and hand-lettered signs on the wall. They may be legitimate, but like my second cousins, Tim and Duane, they are far from respectable, even now.” Such a statement came alongside an honest disclosure: he had first come across these works in a coke dealer’s penthouse.

more here.

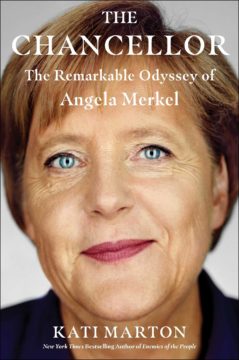

The Remarkable Odyssey of Angela Merkel

Kati Marton at Literary Review:

For much of her sixteen years in office as Germany’s chancellor, Angela Dorothea Merkel, née Kasner, has been ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’, to quote Churchill’s famous dictum on the Soviet Union. Her meteoric rise defied all rational explanation. A woman from East Germany, a scientist with an inbuilt aversion to straddling the political stage and mounting the bully pulpit: how could she succeed in a country with a conservative mind-set which had all but closed out women from professional advancement?

For much of her sixteen years in office as Germany’s chancellor, Angela Dorothea Merkel, née Kasner, has been ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’, to quote Churchill’s famous dictum on the Soviet Union. Her meteoric rise defied all rational explanation. A woman from East Germany, a scientist with an inbuilt aversion to straddling the political stage and mounting the bully pulpit: how could she succeed in a country with a conservative mind-set which had all but closed out women from professional advancement?

Merkel had other drawbacks, too, which in her own eyes militated against her ascent. In June 2005, in the middle of her campaign to be elected chancellor, she approached Tony Blair, who was visiting Berlin, for advice, telling him, ‘I have the following problems: I am a woman, I have no charisma, and I’m not good at communicating.’

more here.

Ann Patchett’s essays unfold her warmth, generosity, and humor

Heller McAlpin in The Christian Science Monitor:

“These Precious Days,” Ann Patchett’s generous new collection of essays, nearly all of which were previously published in periodicals, offers a burst of warm positivity. Like her first collection, “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (2013), this appealing mix of the personal and the professional highlights the centrality of books, family, friendship, and compassion in Patchett’s life. At the heart of “These Precious Days” is the title essay, a tribute to a woman Patchett befriended in what turned out to be the last years of the woman’s life. Patchett, who memorialized her difficult, intense friendship with fellow writer Lucy Grealy in “Truth & Beauty” (2004), has an easier time celebrating her less complicated, serendipitous relationship with Sooki Raphael, Tom Hanks’ longtime personal assistant.

“These Precious Days,” Ann Patchett’s generous new collection of essays, nearly all of which were previously published in periodicals, offers a burst of warm positivity. Like her first collection, “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (2013), this appealing mix of the personal and the professional highlights the centrality of books, family, friendship, and compassion in Patchett’s life. At the heart of “These Precious Days” is the title essay, a tribute to a woman Patchett befriended in what turned out to be the last years of the woman’s life. Patchett, who memorialized her difficult, intense friendship with fellow writer Lucy Grealy in “Truth & Beauty” (2004), has an easier time celebrating her less complicated, serendipitous relationship with Sooki Raphael, Tom Hanks’ longtime personal assistant.

Patchett’s essays often carry life lessons. What she learns from Sooki is to remember to treasure and pay attention to every precious moment. Another lesson here is about the deep gratification of extending oneself. That’s what Patchett did when she opened her Nashville home to Sooki so her new friend could participate in a medical trial not then available in her home state of California. Patchett, a born nurturer, writes that even though she barely knew Sooki at that point, “there have been few moments in my life when I have felt so certain: I was supposed to help.”

Sooki turns out to be an ideal houseguest – self-sufficient, tidy, quiet, thoughtful. When the pandemic hits, they go into lockdown together with Patchett’s husband, Karl VanDevender, a doctor who helped arrange for Sooki’s enrollment in the trial. Patchett spends her days writing or packing books to ship from her closed bookstore. Between treatments, Sooki finally gets to devote herself to her passion: painting. The two women practice yoga and cook vegetarian meals together. “Most of the writers and artists I know were made for sheltering in place,” Patchett writes. “The world asks us to engage, and for the most part we can, but given the choice, we’d rather stay home.”

More here.

Trees alone will not save us

Alun Salt in Botany One:

There’s more recognition that ecological restoration can be an essential tool in fighting climate change, and there are many projects aimed at restoring degraded forests to capture carbon. Still, the focus on forests ignores much of the land in the tropics that would not naturally be forested. A team of scientists is arguing that people need to become aware of other habitats and their value.

There’s more recognition that ecological restoration can be an essential tool in fighting climate change, and there are many projects aimed at restoring degraded forests to capture carbon. Still, the focus on forests ignores much of the land in the tropics that would not naturally be forested. A team of scientists is arguing that people need to become aware of other habitats and their value.

There’s increased understanding that not only do we need to cut carbon dioxide emissions, we also need to pull it from the atmosphere. Recently trees have come into fashion as the answer. This need has led to the Trillion Tree Campaign and a company in the UK planting giant redwoods to offset a lifetime’s carbon on the basis that “planting native trees to combat climate change is a little like bringing a water pistol to a gun fight.” Ecologists working outside forests could feel a little neglected. Research recently published in the Journal of Applied Ecology by Fernando A. O. Silveira and colleagues showed that they’d be right. And it’s not just the public that is fixating on trees. The study shows that scientists and policymakers are focussing disproportionately on trees too. This problem, which they label Biome Awareness Disparity or BAD, could have consequences for conservation in the future.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Upon hearing the glacier’s been declared officially dead

That hollering wind catches again

in my throat the way it once

caught at our tent all night it hasn’t

died down by morning blowing

open my mind’s shutters to that

interminable static snowfield ascent

with neither ropes nor poles

cold’s iron taste sunlight banging

like a gate in my sternum i grew old

expecting the crevasse-edge to crack

breakage i still carry in my pack

though years have fallen through us

and we’ve little occasion to speak

the glacier is dead news i zip

into a cool hidden pocket and keep

walking deforming and flowing

under the weight of zero gathering

a force that sucks the world we

knew through its infinite mouth

by Sara Burant

from the Ecotheo Review

It’s not easy to live in a Mystery

by Charlie Huenemann

Over years of teaching philosophy, I have observed that people fall into two groups with regard to the Biggest Question. The Biggest Question is one that is so big it is hard to fit into words, but here goes: When everything that can be explained has been explained, when we know the truths of physics and brains and psychology and social interactions and so on and so forth, will there still be anything worth wondering about? I am assuming the “wonder” here is a philosophical wonder, not the sort of wonder over whatever happened to my old pocket knife or whatever. It’s the sort of wonder that has a “why-is-there-something-rather-than-nothing” flavor to it. It’s the sort of wonder that doesn’t go away no matter how much is explained.

Some people think that on that sunny day when everything that can be explained has been explained, well then, that will be that. We will understand why things have happened, and how we came to exist, and what we should do if we want to be healthy and happy, and why works of art move us as they do. It’s not that such people are in any way shallow or unimaginative or tone deaf. They are open to the most wonderful experiences of life, along with the most heart-wrenching and most tragic. It’s just that they think these experiences can be explained and understood in all their glory through that explanation. If there is anything “left over” — some stubborn bit of incredulous wonder we just can’t shake — then that too will be explained through some feature of human psychology, like the way those patterns still seem to swirl in a static optical illusion even when you know the trickery behind it. The feeling that there is a Mystery can itself be explained as an illusory sort of feeling, an accidental by-product of the cognitive engine we happen to think with.

But other people think that the Mystery is not an illusion or accident, and that there still would be something worthy of genuine philosophical wonder even when the grand explainers have completed their grand task. Maybe the Mystery is worthy of some kind of worship or spiritual reverence. Maybe it can be reflected in a poem or in music or in a painting, or even in a shared and silent moment with friends. Maybe it is exactly what remains when all explaining is done — as Wittgenstein the Sage once wrote, “Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that it is”. In his terms, the Mystery is precisely that of which we must remain silent, simply because no amount of talking will capture it. These people would say that the first group of people are the ones with the illusion: namely, the illusion that what can’t be explained isn’t real. Read more »

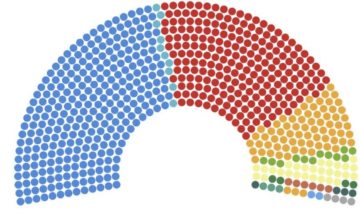

Sometimes It’s Just Math

by John Allen Paulos

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

Since group identity and wokeness arouse so much emotion, a “geologic upheaval of thought” as Proust characterized it, it’s probably best to discuss a couple of simple illustrative scenarios abstractly. Consider, for example, a well-meaning institution, the Earnest Enterprises Foundation say, operating in a community that contains a numerically dominant majority group, Maj, and two subgroups – a substantial minority group, Min, and a smaller minority group, Sm, which has members in group Maj as well as members in group Min. Let’s assume that the group Maj constitutes 75% of this imaginary community, Min the remaining 25%, and let’s also assume that 10% of the community belongs to group Sm, whose members are known to be somewhat marginalized and less likely to self-identify as Sm, self-identity being a somewhat nebulous notion. This latter assumption introduces complications since the extent to which the groups differ, self-identify, and intersect is unknown to the foundation or even to the community. Let’s further assume that only 4% of group Min members self-identify as Sm and 8% of the group Maj members self-identify as Sm.

Making a well-intended attempt to assemble a workforce of 1,000 which “fairly” reflects the community, the foundation most naturally (but not necessarily) prioritizes the Maj-Min dichotomy and hires 750 members of group Maj and 250 members of group Min. But this is problematic since just 10 members of the group Min (4% of 250) would self-identify as being in group Sm, AND 60 members of the group Maj (8% of 750) would self-identify as being in group Sm. Thus ONLY 70 or 7% of all 1,000 workers would be self-identified members of group Sm.

It follows that, despite their best efforts, Earnest Enterprises would still be liable to charges of bias. It could obviously be accused by its Min employees of being anti-SM since only 4% of the Min employees (10 of 250) would be in group Sm, not the assumed community‑wide 10%. Interestingly, the foundation’s group Sm employees could likewise claim that the foundation was anti-Min since only 14.3% of the self-identified Sm members (10 of 70) would be from group Min, not the community‑wide 25%. Read more »

Monday Poem

“Facts are surprisingly delible things.”

………….— Bill Bryson, author

“Trump won.”

……….…— Fox Skews

Facts Are Delible

facts are not indelible after all—

imagine that

now U S headspace is one of delibility,

if such a word exists

—but of course it may, nothing

moors every word to dictionaries:

fresh definition embraced, case closed.

now we just say: fact’s indelibility is erased

what’s interesting though is that

those who scorn indelible facts

genuflect before them when fact is essential

—no heart transplant’s performed through routines

of delible facts, that’s a certainty; nor have

kidneys enjoyed dialysis through ignorance,

or deliberate, delible inconstancy

—nor does any pact, personal or political

survive in a miasma of delible truth or law

by which, instead, we suffer lives of

tooth and claw

Jim Culleny

11/19/21