by Jochen Szangolies

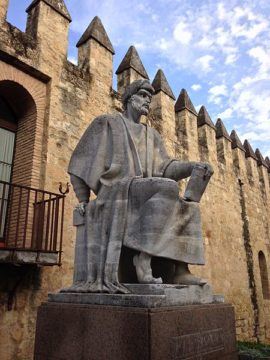

The Incoherence of the Philosophers (Tahâfut al-falâsifa) is an attempt by 11th century Sunni theologian and mystic al-Ghazâlî to refute the doctrines of philosophers such as Ibn Sina (often latinized Avicenna) or al-Fârâbî (Alpharabius), which he viewed as heretical for favoring Greek philosophy over the tenets of Islam. Al-Ghazâlî’s methodological principle was that in order to refute the assertions of the philosophers, one must first be well versed in their ideas; indeed, another work of his, Doctrines of the Philosophers (Maqāsid al-Falāsifa), gives a comprehensive survey of the Neoplatonic philosophy he sought to refute in the Incoherence.

The Incoherence, besides its other qualities, is noteworthy in that it is now regarded as a landmark work in philosophy itself. Ibn Rushd (Averroes), in response, penned the Incoherence of the Incoherence (Tahāfut al-Tahāfut), a turning point away from Neoplatonism to Aristotelianism.

In modern times, most allegations of ‘incoherence’ levied against philosophy come not from the direction of religion, but rather, from scientists’ allegations that their discipline has made philosophy redundant, supplanting it by a better set of tools to investigate the world. The perhaps most well-known example of this is Stephen Hawking’s infamous assertion that ‘philosophy is dead’, but similar sentiments are readily found. While the proponents of such allegations have not always shown shown al-Ghazâlî’s methodological scrupulousness in engaging with the body of thought they seek to refute, these are still weighty charges by some of the leading intellectuals of the day. Read more »

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, there are four types of movies: good-good movies, good-bad movies, bad-good movies, and bad-bad movies. These types can be identified using the Rotten Tomatoes score for each movie, particularly the relationship between the critics’ score and the audience’s score. Let me explain. Rotten Tomatoes is a website that collects movie reviews and assigns them a rating of either “fresh” (if the review is positive) or “rotten” (if the review is negative). It then calculates the percentage of fresh reviews and assigns this as a score to the movie. If the score is 60% or greater, the film itself is considered fresh, whereas if the score is lower than 60%, the film is rotten. This is a useful way of rating a movie, but there’s a problem here, too. Let’s imagine every reviewer gives a movie three out of four stars, indicating a good film but not a great one. These reviews would all be classified as fresh, and the film would receive a misleadingly high score of 100% (The Terminator has a 100% rating, for example, while The Godfather does not). Let’s imagine another film receives all two out of four-star reviews. These would be classified as rotten, and the film would receive a rating of 0%, indicating one of the worst movies of all time. But the movie wouldn’t really be that bad.

According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, there are four types of movies: good-good movies, good-bad movies, bad-good movies, and bad-bad movies. These types can be identified using the Rotten Tomatoes score for each movie, particularly the relationship between the critics’ score and the audience’s score. Let me explain. Rotten Tomatoes is a website that collects movie reviews and assigns them a rating of either “fresh” (if the review is positive) or “rotten” (if the review is negative). It then calculates the percentage of fresh reviews and assigns this as a score to the movie. If the score is 60% or greater, the film itself is considered fresh, whereas if the score is lower than 60%, the film is rotten. This is a useful way of rating a movie, but there’s a problem here, too. Let’s imagine every reviewer gives a movie three out of four stars, indicating a good film but not a great one. These reviews would all be classified as fresh, and the film would receive a misleadingly high score of 100% (The Terminator has a 100% rating, for example, while The Godfather does not). Let’s imagine another film receives all two out of four-star reviews. These would be classified as rotten, and the film would receive a rating of 0%, indicating one of the worst movies of all time. But the movie wouldn’t really be that bad. Is loneliness a choice? Is love?

Is loneliness a choice? Is love? Presidency College had a good Department of Economics and Political Science. I’d say that the teaching standard at my time there would compare quite favorably with the standard I found later when teaching undergraduate classes in Berkeley. I remember in my first lecture in Berkeley in a large undergraduate class I was using some bit of calculus. After my class a female student came to see me to complain about the use of calculus in class. I told her that I was not using any advanced calculus, so if she brushed up her high school-level calculus she should have no difficulty in following the class. She said that in her high school in Carmel, a California coastal town, there was the option to take either calculus or yoga, and she had chosen the latter. I told her, unhelpfully, that this was a choice unheard-of in the land of yoga, India, and, I thought to myself, certainly in Presidency College.

Presidency College had a good Department of Economics and Political Science. I’d say that the teaching standard at my time there would compare quite favorably with the standard I found later when teaching undergraduate classes in Berkeley. I remember in my first lecture in Berkeley in a large undergraduate class I was using some bit of calculus. After my class a female student came to see me to complain about the use of calculus in class. I told her that I was not using any advanced calculus, so if she brushed up her high school-level calculus she should have no difficulty in following the class. She said that in her high school in Carmel, a California coastal town, there was the option to take either calculus or yoga, and she had chosen the latter. I told her, unhelpfully, that this was a choice unheard-of in the land of yoga, India, and, I thought to myself, certainly in Presidency College. Recently I was sent an article about “

Recently I was sent an article about “ Humans have long wondered why we sleep. A well-rested prehistoric mind probably pondered the question, long before Galileo thought to predict the period of the pendulum or to understand how fast objects fall. Why must we put ourselves into this potentially endangering state, one that consumes about a third of our adult lives and even more of our childhood? And we don’t do it grudgingly – why do we, along with dogs, lions and virtually every other animal, apparently enjoy it? Unlike measuring the period of the pendulum, scientists would have to wait much longer to obtain reliable answers, since it’s not so easy to sleep while strangers watch. Doing so involves building sleep disorder clinics for humans and elaborate structures such as platypusariums to observe the REM (rapid eye movement) repose of platypuses.

Humans have long wondered why we sleep. A well-rested prehistoric mind probably pondered the question, long before Galileo thought to predict the period of the pendulum or to understand how fast objects fall. Why must we put ourselves into this potentially endangering state, one that consumes about a third of our adult lives and even more of our childhood? And we don’t do it grudgingly – why do we, along with dogs, lions and virtually every other animal, apparently enjoy it? Unlike measuring the period of the pendulum, scientists would have to wait much longer to obtain reliable answers, since it’s not so easy to sleep while strangers watch. Doing so involves building sleep disorder clinics for humans and elaborate structures such as platypusariums to observe the REM (rapid eye movement) repose of platypuses. It’s not often that a shotgun-wielding thief and killer comes to be seen as possessing a moral core. But then it’s not often that you have a character like Omar Little. Or an actor like Michael K Williams to bring him to life. Or a TV series like The Wire that allowed both character and actor to breathe.

It’s not often that a shotgun-wielding thief and killer comes to be seen as possessing a moral core. But then it’s not often that you have a character like Omar Little. Or an actor like Michael K Williams to bring him to life. Or a TV series like The Wire that allowed both character and actor to breathe. When I left Stanford to join Google as an AI research scientist, I “went across the street,” as the saying went. I had been a young assistant professor, first at Georgia Tech and then at Stanford, doing research that was partially funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). At one point, I brought up the ethical issues of researching surveillance technology with the DARPA program manager, but frankly, raising ethical concerns in such a competitive environment felt a bit like labeling myself a troublemaker.

When I left Stanford to join Google as an AI research scientist, I “went across the street,” as the saying went. I had been a young assistant professor, first at Georgia Tech and then at Stanford, doing research that was partially funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). At one point, I brought up the ethical issues of researching surveillance technology with the DARPA program manager, but frankly, raising ethical concerns in such a competitive environment felt a bit like labeling myself a troublemaker. For almost two decades, I have been attempting to understand the origins and drivers of the

For almost two decades, I have been attempting to understand the origins and drivers of the  The Irish writer Colm Tóibín is a busy man. Since he published his first novel, “

The Irish writer Colm Tóibín is a busy man. Since he published his first novel, “