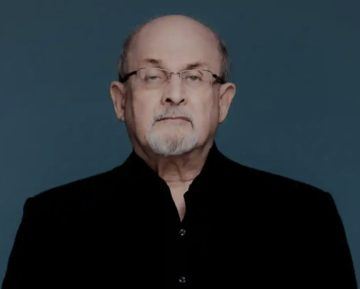

Shelley Hepworth in The Guardian:

Out of the gloom Salman Rushdie floats into view, his familiar face with short beard and glasses hovering on screen in front of a library that should win any competition for the most impressive Zoom bookshelf backdrop.

Out of the gloom Salman Rushdie floats into view, his familiar face with short beard and glasses hovering on screen in front of a library that should win any competition for the most impressive Zoom bookshelf backdrop.

From his New York apartment he is here to share three things: he has made a deal to publish his next work of fiction as a serialised novella on Substack; he intends to fulfil a long held, once thwarted desire to be a film critic; and he still doesn’t have the courage to write poetry.

“I got very attracted to the idea recently, in this strange year and a half, of trying out things I’ve never done before,” he says.

“It’s to do with this enforced condition we’ve all been in of being pushed inwards … I published this book of essays [which was] the 20th book and I’m already writing the 21st book, which is a novel. I just thought: do something else. And exactly the moment I was thinking that this project cropped up.”

“This project” is Substack and came about after the newsletter platform wrote to Rushdie’s literary agent, Andrew Wylie, who asked him if it was something he wanted to do.

More here. And you can read and subscribe to Salman Rushdie’s Substack Newsletter here.

There is no general theory of problem-solving, or even a reliable set of principles that will usually work. It’s therefore interesting to see how our brains actually go about solving problems. Here’s an interesting feature that you might not have guessed: when faced with an imperfect situation, our first move to improve it tends to involve adding new elements, rather than taking away. We are, in general, resistant to subtractive change. Leidy Klotz is an engineer and designer who has worked with psychologists and neuroscientists to study this phenomenon. We talk about how our relative blindness to subtractive possibilities manifests itself, and what lessons might be for design more generally.

There is no general theory of problem-solving, or even a reliable set of principles that will usually work. It’s therefore interesting to see how our brains actually go about solving problems. Here’s an interesting feature that you might not have guessed: when faced with an imperfect situation, our first move to improve it tends to involve adding new elements, rather than taking away. We are, in general, resistant to subtractive change. Leidy Klotz is an engineer and designer who has worked with psychologists and neuroscientists to study this phenomenon. We talk about how our relative blindness to subtractive possibilities manifests itself, and what lessons might be for design more generally. Could admitting millions more immigrants over the next decade be the jolt the U.S. needs to revive its economy, culture, and politics? After four years of restrictionism under President Trump, ongoing border controversies, and an escalating culture war led by nativists, this idea may seem counterintuitive or even far-fetched. But recent labor market trends, demographic changes, and even accelerating climate change all point to dramatically increased immigration as a logical catalyst for national renewal. Becoming the most welcoming country on Earth for migrants—breathing new life into our most flattering, if too often inaccurate self-image—could be our salvation.

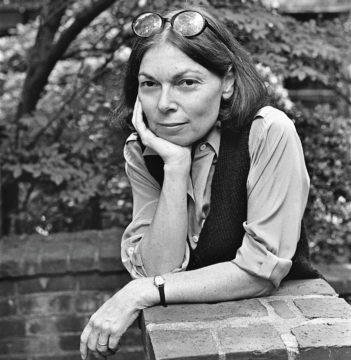

Could admitting millions more immigrants over the next decade be the jolt the U.S. needs to revive its economy, culture, and politics? After four years of restrictionism under President Trump, ongoing border controversies, and an escalating culture war led by nativists, this idea may seem counterintuitive or even far-fetched. But recent labor market trends, demographic changes, and even accelerating climate change all point to dramatically increased immigration as a logical catalyst for national renewal. Becoming the most welcoming country on Earth for migrants—breathing new life into our most flattering, if too often inaccurate self-image—could be our salvation. One of Janet’s themes as a writer was self-delusion in all its guises—the propensity we all share for telling ourselves stories that, at the very least, reconfigure events to cast ourselves in a more favorable light. I was stung by one line in the profile: that (I paraphrase) in all our time together, nothing I said about my work was of the slightest interest to her. Once my vanity recovered from the dismissal of my “thinking,” the veracity of Janet’s verdict was clear. (The passage continued to insist that nothing any artist ever says about their work is of interest.) I eventually came to feel more or less the same way—that nothing anybody says about their intentions or “process” is of any particular relevance unless it’s a one-liner by de Kooning. Who cares? This attitude is at odds with the prevailing reverence for that peculiar literary artifact, the artist’s statement, but such was the incontrovertible nature of Janet’s contrarianism. Like any good analyst, she was only interested in the story behind the story. The fact that a belief is widely held should be enough to raise our suspicions.

One of Janet’s themes as a writer was self-delusion in all its guises—the propensity we all share for telling ourselves stories that, at the very least, reconfigure events to cast ourselves in a more favorable light. I was stung by one line in the profile: that (I paraphrase) in all our time together, nothing I said about my work was of the slightest interest to her. Once my vanity recovered from the dismissal of my “thinking,” the veracity of Janet’s verdict was clear. (The passage continued to insist that nothing any artist ever says about their work is of interest.) I eventually came to feel more or less the same way—that nothing anybody says about their intentions or “process” is of any particular relevance unless it’s a one-liner by de Kooning. Who cares? This attitude is at odds with the prevailing reverence for that peculiar literary artifact, the artist’s statement, but such was the incontrovertible nature of Janet’s contrarianism. Like any good analyst, she was only interested in the story behind the story. The fact that a belief is widely held should be enough to raise our suspicions. It seemed like a good idea to avoid the screen, but my resolve didn’t last long. The book I was reading at the time, On the Natural History of Destruction, a collection of W. G. Sebald’s lectures and essays about the literature of the Second World War, concludes with a piece on the German-Swedish writer Peter Weiss. Like most English-speakers who had heard of him, I knew of Weiss only as the author of the play The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (Marat/Sade for short), which had been made into a film starring Patrick Magee and Glenda Jackson during the brief vogue for interwar European aesthetic programs—in this case Brecht’s Epic Theater and Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty—among the countercultures of Britain and the United States in the 1960s. Sebald, however, mentions Marat/Sade only in passing. Instead, he discusses Weiss’s early career as a painter; his surreal autobiographical novella, Leavetaking; his controversial documentary play about the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, The Investigation; and, at greatest length, his late three-volume novel about the German anti-fascist underground, The Aesthetics of Resistance.

It seemed like a good idea to avoid the screen, but my resolve didn’t last long. The book I was reading at the time, On the Natural History of Destruction, a collection of W. G. Sebald’s lectures and essays about the literature of the Second World War, concludes with a piece on the German-Swedish writer Peter Weiss. Like most English-speakers who had heard of him, I knew of Weiss only as the author of the play The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (Marat/Sade for short), which had been made into a film starring Patrick Magee and Glenda Jackson during the brief vogue for interwar European aesthetic programs—in this case Brecht’s Epic Theater and Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty—among the countercultures of Britain and the United States in the 1960s. Sebald, however, mentions Marat/Sade only in passing. Instead, he discusses Weiss’s early career as a painter; his surreal autobiographical novella, Leavetaking; his controversial documentary play about the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, The Investigation; and, at greatest length, his late three-volume novel about the German anti-fascist underground, The Aesthetics of Resistance. Last month, when Samina Farooq, a domestic worker, learned that a fellow female worker in Lahore had been beaten by her employer for spilling milk on the floor, she went to see her. Her message: You should quit now. “Bibis [female employers] beat us for dropping milk on the floor or deduct a portion of our salary if we mistakenly burn a piece of cloth when ironing. Are we not humans? Can’t we make mistakes?” says Ms. Farooq. After the employer acknowledged that she had treated her maid unfairly, the maid agreed to stay on. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that Pakistan has more than 8.5 million domestic workers, mostly women and children. Some suffer appalling abuse at the hands of their employers. Last year an

Last month, when Samina Farooq, a domestic worker, learned that a fellow female worker in Lahore had been beaten by her employer for spilling milk on the floor, she went to see her. Her message: You should quit now. “Bibis [female employers] beat us for dropping milk on the floor or deduct a portion of our salary if we mistakenly burn a piece of cloth when ironing. Are we not humans? Can’t we make mistakes?” says Ms. Farooq. After the employer acknowledged that she had treated her maid unfairly, the maid agreed to stay on. The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that Pakistan has more than 8.5 million domestic workers, mostly women and children. Some suffer appalling abuse at the hands of their employers. Last year an  T

T