Month: September 2021

Occupy Wall Street at 10: What It Taught Us, and Why It Mattered

Micah L. Sifry in The New Republic:

Micah L. Sifry in The New Republic:

Ten years ago today, on September 17, 2011, a small band of anarchists, artists, and anti-poverty organizers convened themselves in Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan, steps from the New York Stock Exchange. They were there to challenge the power of Wall Street and also to try something new in the annals of modern American protest movements: to be a democratic assembly of all who wanted to participate in deciding how and what they would do next. On their first night together that Saturday, perhaps 100 or 200 at best camped out under the park’s 55 honey locust trees.

At first, they were tolerated by the police, since they had stumbled by good fortune into a safe harbor—a privately owned public park that legally allowed people to remain there 24 hours a day. And they were ignored, or derided, by the media, which had seen many Wall Street protests come and go. Over the next few days, their numbers grew modestly while they established working groups for everything from food and health care to a people’s library and scrambled to spread their own messages through the internet. Five days after the Zuccotti occupation began, a nearby protest against the execution of Troy Davis, a Black man in Georgia, brought hundreds of new and somewhat more diverse faces down to the plaza. But it wasn’t until the next Saturday, when the police attacked a column of marchers and one white-shirted deputy was caught on video viciously pepper-spraying a group of women who were already detained, that support for Occupy in New York started to surge.

More here.

Industrial Policy’s Comeback

Mariana Mazzucato, Rainer Kattel, and Josh Ryan-Collins over at Boston Review:

Mariana Mazzucato, Rainer Kattel, and Josh Ryan-Collins over at Boston Review:

When President Joe Biden campaigned last year under the slogan “build back better,” he signaled a break with decades of economic thinking that prescribed a limited government role in the economy. As the New York Times put it in April, Biden’s proposal to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030 is “perhaps the greatest bet in recent American history on what economists call industrial policy, the idea that the government can steer the development of jobs and industries in the economy.”

The United States is not alone. Countries throughout Europe and elsewhere are increasingly turning to the view that governments should use industrial policy to tackle grand challenges. Recognizing this trend, the International Monetary Fund issued a report in 2019 called “The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy.”

Why could this policy “not be named”? The short answer is that industrial policy was one of the many casualties of an international shift in economic policy that began in the 1980s and flourished under the administrations of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom. The emergent sensibility—what we now call neoliberalism—was codified in 1989 in the Washington Consensus, which championed privatization, deregulation, and free trade. Along with these central pillars came an emphasis on low budget deficits, independent central banks focused on low inflation, and the liberalization of trade and foreign direct investment. This outlook was deeply confident in markets and deeply skeptical of government action, beyond the state’s limited role in enforcing property rules and investing in education and defense. “On the basis of an exhaustive review of the experience of developing economies during the last thirty years,” the World Bank summed up in the early 1990s, “attempts to guide resource allocation with nonmarket mechanisms have generally failed to improve economic performance.”

Today it is precisely those “market mechanisms” that appear not to have delivered on their promise.

More here.

Rating politics: The impact of politics and policy choice on sovereign credit ratings

The Sorcerer, On Roberto Calasso (1941 – 2021)

Francesco Pacifico in Sidecar (photo by Erling Mandelmann):

Roberto Calasso died this summer at the age of eighty. Among the unpindownable Italian erudites – Eco, Calvino, Pasolini – the author of the international bestseller The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony (1988), a hybrid meditation on the enduring relevance of Greek myth, is perhaps the hardest to figure out. The Marriage was the second chapter of a hazy, complex and confounding project – Calasso called it an ‘opera’ and would never explain much further – that might be described as a sustained effort to unlock the mystical potential of literature. Extending to eleven volumes with La tavoletta dei destini (2020), it ranges across world history and geography, freely connecting Kafka and Baudelaire, the Vedas and the Bible, Tiepolo and Talleyrand, Mesopotamian and Greek mythology. Of the first installment, The Ruin of Kasch (1983) – whose wandering, eclectically citational reflections on ancient ritual and the nature of the modern established his procedure – Calasso wrote that he wanted to steer clear of the essay form as it had become ‘sclerotized’. ‘From aphorism to brief poem, from cogent analysis of some specific issue to narrated scene’, the book he’d written was rather ‘a whole host of forms…’

Calasso’s hybrids gained worldwide traction in the cosmopolitan eighties and nineties, touted by stars of international letters like Brodsky and Rushdie – the latter praising the erudition and mix of novelistic and essayistic in his book on Vedic theology, Ka (1996). Not perceived as part of a cohort or scene (in contrast to Pasolini and Nuovi Argomenti, or Eco and the Gruppo 63), Calasso was never characterised as particularly Italian, and this always inhibited popular understanding of his work.

More here.

Gnosticism – Cathars and Catharism: Historical Fact or a Delusion of the Inquisition?

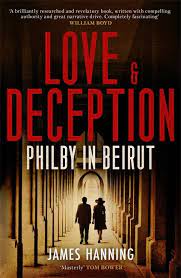

‘Love and Deception: Philby in Beirut’ by James Hanning

John Banville at The Guardian:

In a coolly furious essay published in book form in 1968, Hugh Trevor-Roper singled out Kim Philby’s “truly extraordinary egotism and complacency” as forces that seemed to the historian “to have dominated Philby’s character and determined his lonely and difficult course”. Trevor-Roper knew whereof he spoke, for he had served with the British Secret Intelligence Service during the war and saw much of Philby during those years. His observations on his former friend are shrewd. Only a man who believed in himself utterly could have given himself utterly to a cause, as Philby did.

In a coolly furious essay published in book form in 1968, Hugh Trevor-Roper singled out Kim Philby’s “truly extraordinary egotism and complacency” as forces that seemed to the historian “to have dominated Philby’s character and determined his lonely and difficult course”. Trevor-Roper knew whereof he spoke, for he had served with the British Secret Intelligence Service during the war and saw much of Philby during those years. His observations on his former friend are shrewd. Only a man who believed in himself utterly could have given himself utterly to a cause, as Philby did.

Yet he was no fanatic; anything but. John le Carré – who, incidentally, Trevor-Roper strongly attacks in his Philby monograph – pointed out that in the depths of the “fanatic heart” there lurks a doubt, and doubt, in such a heart, is a fatal weakness.

more here.

Tearing Richard Powers A New One

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

“The world had enough novels,” Richard Powers wrote in “Galatea 2.2,” his semi-autobiographical and arguably best novel, published in 1995. “Certain writers were best paid to keep their fields out of production.”

“The world had enough novels,” Richard Powers wrote in “Galatea 2.2,” his semi-autobiographical and arguably best novel, published in 1995. “Certain writers were best paid to keep their fields out of production.”

Among those writers, a quarter of a century later, may be Powers himself. His new one, “Bewilderment,” is so meek, saccharine and overweening in its piety about nature that even a teaspoon of it numbs the mind.

“Bewilderment” is the follow-up to “The Overstory” (2018), his beloved novel about trees, the importance of maintaining forests and people, in that order. It won a Pulitzer Prize and made Powers something close to a secular saint. Let no one say it was overrated.

more here.

Saturday Poem

All My Friends Are Finding New Beliefs

All my friends are finding new beliefs.

This one converts to Catholicism and this one to trees.

In a highly literary and hitherto religiously-indifferent Jew

God whomps on like a genetic generator.

Paleo, Keto, Zone, South Beach, Bourbon.

Exercise regimens so extreme she merges with machine.

One man married a woman twenty years younger

and twice in one brunch used the word verdant;

another’s brick-fisted belligerence gentles

into dementia, and one, after a decade of finical feints and teases

like a sandpiper at the edge of the sea,

decides to die.

Priesthoods and beasthoods, sombers and glees,

high-styles renunciations and avocations of dirt,

sobrieties, satieties, pilgrimages to the very bowels of being …

All my friends are finding new beliefs

and I am finding it harder and harder to keep track

of the new gods and the new loves,

and the old gods and the old loves,

and the days have daggers, and the mirrors motives,

and the planet’s turning faster in the blackness,

and my nights, and my doubts, and my friends,

my beautiful, credible friends.

by Christian Wiman

from the Poetry Foundation

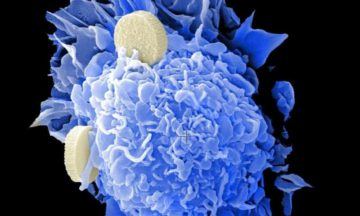

Capturing origins and early adaptive processes underlying therapy response to cancer treatments

Bob Yirka in Phys.Org:

A team of researchers with biotechnology corporation Genentech Inc., has developed a new way to capture the origins and early adaptive processes that are involved in therapy responses to cancer treatments. In their paper published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, the group describes how their new system can be used to help treat resistant types of cancer.

A team of researchers with biotechnology corporation Genentech Inc., has developed a new way to capture the origins and early adaptive processes that are involved in therapy responses to cancer treatments. In their paper published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, the group describes how their new system can be used to help treat resistant types of cancer.

As the researchers note, the current approach to treating patients with cancer is to give them therapies that their doctor believes are best suited to the kind of cancer they have and then watching to see how well it works—and then modifying the approach if the outcome is less than hoped due to resistance. To improve the process, the team has developed a system that is able to take into account pre-existing features of cancer cells and the changes that might have come about because of them that could lead to treatment resistance. The new system, called TraCe-seq involves analyzing clonal responses to various treatments applied to mutated lung cancer cells—using a single-cell RNA sequencing method. As part of its development, the researchers used EGFR-targeting therapies, which included kinase inhibitors that have been shown to disrupt enzyme binding.

The researchers note that the system is reliant on combinations of different cellular barcoding along with sequential single-cell sequencing. The bar-coding, they further note, allows for using clonal fitness with untreated cells along with those that are exposed to a variety of different therapies.

More here.

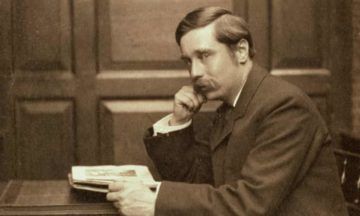

How the 21st century would have disappointed HG Wells

Elif Shafak in The Guardian:

In his writings, Wells conveyed a plethora of futuristic prophecies, from space travel to genetic engineering, from the atomic bomb to the world wide web. There was no other fiction writer who saw into the future of humankind as clearly and boldly as he did.

In his writings, Wells conveyed a plethora of futuristic prophecies, from space travel to genetic engineering, from the atomic bomb to the world wide web. There was no other fiction writer who saw into the future of humankind as clearly and boldly as he did.

Were he to have been alive at the very end of the 20th century, what would he have made of that world? I am especially curious to know what he would have thought about the unbridled optimism characteristic of the era, an optimism shared by liberal politicians, political scientists and Silicon Valley alike. The rosy conviction that western democracy had triumphed once and for all and that, thanks to the proliferation of digital technologies, the whole world would, sooner or later, become one big democratic global village. The naive expectation that, if you could only spread information freely beyond borders, people would become informed citizens, and thus make the right choices at the right time. If history is by definition linear and progressive – if there is no viable alternative to liberal democracy – why should you worry about the future of human rights, or rule of law, or freedom of speech or media diversity? The western world was regarded as safe, solid, stable. Democracy, once achieved, could not be disintegrated. How could anyone who had tasted the freedoms of democracy ever agree to discard it to the winds?

Fast forward, and today this dualistic way of seeing the world is shattered. The ground beneath our feet does not feel that solid any more. We have entered the Age of Angst. Ours is the age of pessimism. Ours is a world that is hurting. If Wells were alive today, what would he think of this new century with its increasing polarisation, rising populist authoritarianism, and the bewildering pace of consumption – including consumption of misinformation – all of which are exacerbated by digital technologies?

More here.

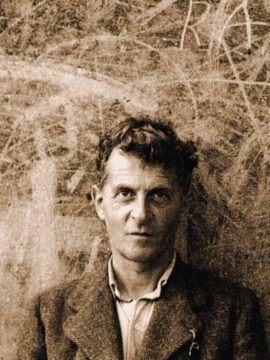

Ludwig Wittgenstein: a mind on fire

Ray Monk in The New Statesman:

In 1920, after failing five times to find a publisher for his newly finished book, Tractatus Logico Philosophicus, the Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein consoled himself in a letter to Bertrand Russell:

In 1920, after failing five times to find a publisher for his newly finished book, Tractatus Logico Philosophicus, the Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein consoled himself in a letter to Bertrand Russell:

Either my piece is a work of the highest rank, or it is not a work of the highest rank. In the latter (and more probable) case I myself am in favour of it not being printed. And in the former case it’s a matter of indifference whether it’s printed twenty or a hundred years sooner or later. After all, who asks whether the Critique of Pure Reason… was written in 17x or y.

The following year the book finally found a publisher. The 100th anniversary of its publication this year is being celebrated all over the world by exhibitions, conferences, radio programmes and articles, all of which attest to its recognition as “a work of the highest rank”.

More here.

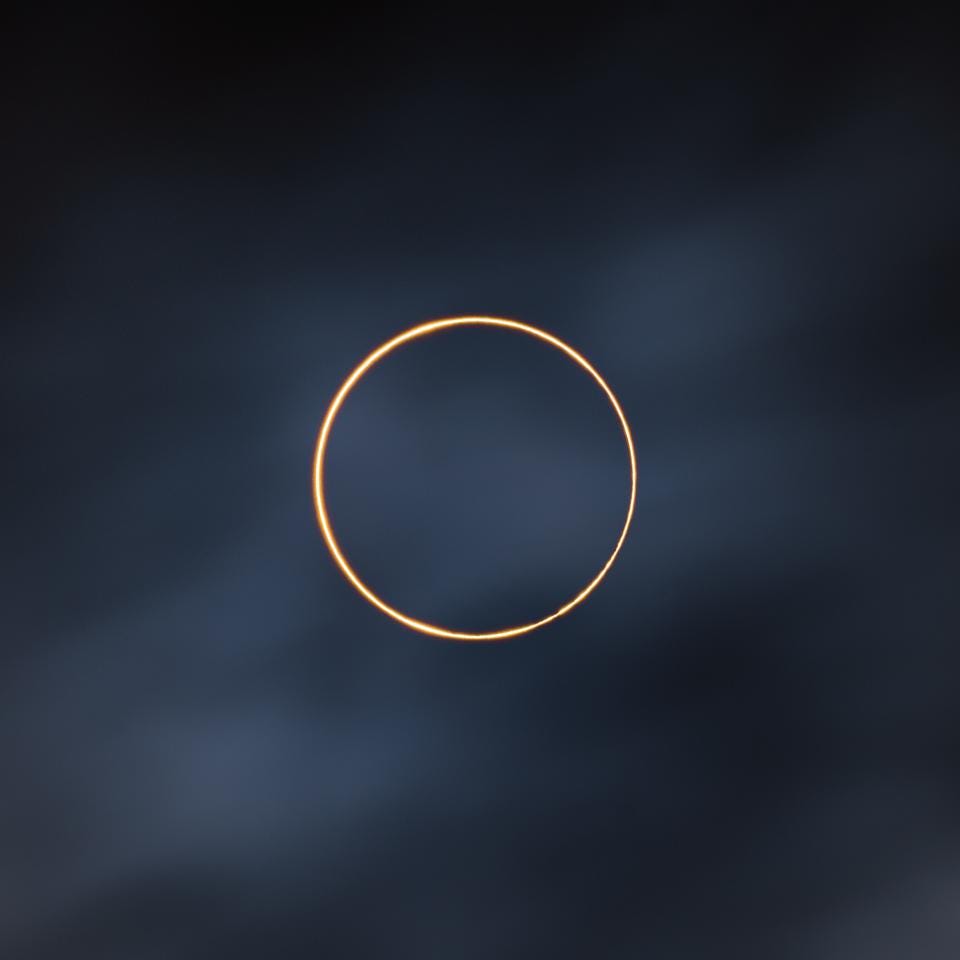

‘Golden Ring Of Fire’ Solar Eclipse Image Wins ‘Astronomy Photographer Of The Year’ Competition

More here.

Aerial Sheep Herding in Yokneam

Aerial Sheep Herding in Yokneam from Colossal on Vimeo.

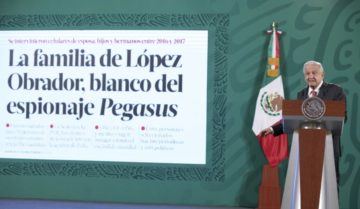

Israel’s Pegasus: Is your phone a ‘24-hour surveillance device’?

Belen Fernandez at Al Jazeera:

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the iPhones of nine Bahraini activists – including two dissidents exiled in London and three members of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights – were hacked using the Pegasus spyware that was developed by NSO Group, an Israeli cyber-surveillance firm regulated by Israel’s defence ministry.

Between June 2020 and February 2021, the iPhones of nine Bahraini activists – including two dissidents exiled in London and three members of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights – were hacked using the Pegasus spyware that was developed by NSO Group, an Israeli cyber-surveillance firm regulated by Israel’s defence ministry.

The hackings were revealed in a new report from Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, which has studied Pegasus extensively along with related nefarious modern phenomena.

As the Guardian notes, Pegasus is “perhaps the most powerful piece of spyware ever developed” and can turn a mobile phone into a “24-hour surveillance device” – harvesting messages, passwords, photos, internet searches, and other data and seizing control of the camera and microphone.

This can all be done via “zero-click” technology, meaning that one does not have to click on a compromised link or do anything else for one’s phone to become infected.

More here.

The First Humans out of Africa: Hominin Dispersal in the Old World

The Woman Who Knew Too Much

Aleksandra Wagner at Cabinet Magazine:

In the 1770s, the Paduan philosopher, natural historian, and Augustinian abbot Alberto Fortis (1741–1803) undertook several journeys to the other side of Adriatic, one of them to the lands of the Morlacchi. His travels were memorialized as Viaggio in Dalmazia, an epistolary travelogue printed in Venice in 1774 and translated into German two years later. It inspired Goethe to retranslate a folk poem collected by Fortis for his book and to recommend it for inclusion in Herder’s collection of Volkslieder. Goethe’s translation, initially published anonymously, made the “Xalostna pjesanca plemenite Asan-Aghinize” one of the most famous folkloric artifacts of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe.

In the 1770s, the Paduan philosopher, natural historian, and Augustinian abbot Alberto Fortis (1741–1803) undertook several journeys to the other side of Adriatic, one of them to the lands of the Morlacchi. His travels were memorialized as Viaggio in Dalmazia, an epistolary travelogue printed in Venice in 1774 and translated into German two years later. It inspired Goethe to retranslate a folk poem collected by Fortis for his book and to recommend it for inclusion in Herder’s collection of Volkslieder. Goethe’s translation, initially published anonymously, made the “Xalostna pjesanca plemenite Asan-Aghinize” one of the most famous folkloric artifacts of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe.

The sorrowful poem about Hasanaginica, the noble wife of Hasan Aga, opens with the literary gesture known as “Slavic antithesis.” This odd literary conceit refers to the following formula: a question is asked; an echoing suspense, in the negative, is offered first; and then we learn the answer.

more here.

The Real Horror of ‘Night in the Woods’

Ellie Kovach at The Believer:

By most reasonable metrics, the 2017 indie adventure game Night In the Woods is not a horror game. There are no jump scares, no dread-inducing meta experiments, no resource scarcity (no item management to speak of, actually), and no tense gameplay sequences. Night In the Woods is a story about a 20-year-old cat named Mae Borowski who has returned to her hometown of Possum Springs after deciding to drop out of college, and you spend the majority of the game exploring her relationships with the townsfolk—with her neighbors, with her parents, with the friends she left behind. Aside from a few rhythm game inspired musical sequences, it is a relatively quiet game that thrives on rich dialogue and character interactions.

By most reasonable metrics, the 2017 indie adventure game Night In the Woods is not a horror game. There are no jump scares, no dread-inducing meta experiments, no resource scarcity (no item management to speak of, actually), and no tense gameplay sequences. Night In the Woods is a story about a 20-year-old cat named Mae Borowski who has returned to her hometown of Possum Springs after deciding to drop out of college, and you spend the majority of the game exploring her relationships with the townsfolk—with her neighbors, with her parents, with the friends she left behind. Aside from a few rhythm game inspired musical sequences, it is a relatively quiet game that thrives on rich dialogue and character interactions.

Lurking under the surface, however, is a game about existential dread, mental illness, despair, cosmic horror, and feelings of helplessness.

more here.

The Uncanny Valley of “I’m Your Man”

Anthony Lane in The New Yorker:

Allow me to introduce Tom. You’ll like him. Tom is handsome and sleek, with a discreet dress sense and all the social graces, but what really counts is that he’s kind. You can’t beat kindness. He won’t bug you or bore you, and so exactly will he meet your needs, whatever they are, that it’s as if he understood, in advance, what they were going to be. And did I mention that he knows a lot? As in, everything? To sum up, Tom is quite a guy. If you want to be picky, or downright rude, you could point out that he’s a robot, but hey: nobody’s perfect.

Allow me to introduce Tom. You’ll like him. Tom is handsome and sleek, with a discreet dress sense and all the social graces, but what really counts is that he’s kind. You can’t beat kindness. He won’t bug you or bore you, and so exactly will he meet your needs, whatever they are, that it’s as if he understood, in advance, what they were going to be. And did I mention that he knows a lot? As in, everything? To sum up, Tom is quite a guy. If you want to be picky, or downright rude, you could point out that he’s a robot, but hey: nobody’s perfect.

Tom is played by Dan Stevens in “I’m Your Man,” a new German comedy from the director Maria Schrader. No date is given, but the setting appears to be the near future. It looks just like the present day, only cleaner—a good joke in itself, given that, as moviegoers, we have had it drummed into us that the world to come will be dystopically horrible. Yet here we are, in and around Berlin, mostly in blessed sunshine. The streets are so uncrowded as to make us wonder if, and how, the population has been thinned out, though we hear not a whisper of catastrophe.

More here.

What Is Life?

Let me tell you what it’s like to be an astrobiologist.

I painted a white picket fence this summer. No one asked me to. It was a task I’d set myself without realizing what a long-winded and frustrating process it would be. But eventually that endless scraping, priming, painting, and maneuvering settled into something therapeutic, even meditative.

I’d paint the apex—dab, dab—run down the narrow sides, coat the smooth front, shuffle along, repeat. All the while acutely aware of being surrounded by the churn of summer in the northern hemisphere of a living planet. Long-legged harvestmen arachnids staking their turf from fence post to fence post. Hummingbirds squabbling noisily from within their strange half-bird, half-insect dimension. Plant life bursting from every seam of soil; from the dusty grains between paving slabs to the mulchy damp beneath maple trees, green shoots fighting a slow-motion war for atoms and photons. The kind of war that likely plays out across the observable universe in any place where matter has become structured into the self-propagating, energy-hungry stuff we call life.

More here.