Holland Cotter in The New York Times:

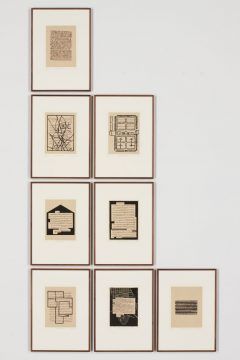

Ms. Hashmi, who preferred to identify herself professionally by only her first name, became internationally known for woodcuts and intaglio prints, many combining semiabstract images of houses and cities she had lived in accompanied by inscriptions written in Urdu, a language spoken primarily by Muslim South Asians. (It is the official national language of Pakistan.) In South Asia itself, she is particularly revered as a representative of a now-vanishing generation of artists who were alive during the 1947 partition of the subcontinent along ethnic and religious lines, a catastrophic event that, she felt, cut her loose from her roots and haunted her life and work. Zarina Rashid was born on July 16, 1937, the youngest of five children, in the small Indian town of Aligarh, where her father, Sheikh Abdur Rashid, taught at Aligarh Muslim University. Her mother, Fahmida Begum, was a homemaker. In her 2018 memoir, “Directions to My House,” Ms. Hashmi described growing up in what she called a traditional Muslim home. In hot months she and her older sister Rani would sleep outdoors “under the stars and plot our journeys in life.” The floor plan of her childhood house, whose walls enclosed a fragrant garden, became a recurrent presence in her art. That life abruptly ended with the partition of India and the violence between Muslims and Hindus. For safety, her father sent the family to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan. The experience of fleeing to a refugee camp and seeing bodies left in the road stayed with Ms. Hashmi. “These memories formed how I think about a lot of things: fear, separation, migration, the people you know, or think you know,” she wrote in her memoir.

Ms. Hashmi, who preferred to identify herself professionally by only her first name, became internationally known for woodcuts and intaglio prints, many combining semiabstract images of houses and cities she had lived in accompanied by inscriptions written in Urdu, a language spoken primarily by Muslim South Asians. (It is the official national language of Pakistan.) In South Asia itself, she is particularly revered as a representative of a now-vanishing generation of artists who were alive during the 1947 partition of the subcontinent along ethnic and religious lines, a catastrophic event that, she felt, cut her loose from her roots and haunted her life and work. Zarina Rashid was born on July 16, 1937, the youngest of five children, in the small Indian town of Aligarh, where her father, Sheikh Abdur Rashid, taught at Aligarh Muslim University. Her mother, Fahmida Begum, was a homemaker. In her 2018 memoir, “Directions to My House,” Ms. Hashmi described growing up in what she called a traditional Muslim home. In hot months she and her older sister Rani would sleep outdoors “under the stars and plot our journeys in life.” The floor plan of her childhood house, whose walls enclosed a fragrant garden, became a recurrent presence in her art. That life abruptly ended with the partition of India and the violence between Muslims and Hindus. For safety, her father sent the family to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan. The experience of fleeing to a refugee camp and seeing bodies left in the road stayed with Ms. Hashmi. “These memories formed how I think about a lot of things: fear, separation, migration, the people you know, or think you know,” she wrote in her memoir.

…Near-abstract images of houses recurred. A 1981 cast-paper relief called “Homecoming” is essentially an aerial view of a courtyard surrounded by arches, reminiscent of the one in her childhood home. A bronze sculpture, “I Went on a Journey III” (1991), is a miniature house on wheels. The prints in a portfolio called “Homes I Made/A Life in Nine Lines” are based on blueprints of houses that Ms. Hashmi had lived in from 1958 onward. And in a print series called “Letters From Home,” Ms. Hashmi overlaid images of both house and city onto the texts of letters, often about family deaths and loss, that her sister Rani had written to her but never sent. Significantly, each letter is transcribed in Urdu script, as are many identifying labels in other prints. Urdu is slowly going out of currency in sectarian India, but for Ms. Hashmi it defined “home” as surely as images of maps and houses did. “The biggest loss for me is language,” she told Ms. Stewart. “Specifically poetry. Before I go to bed lately, thanks to YouTube, I listen to the recitation of poetry in Urdu. I jokingly say I have lived a life in translation.”

More here.