Arthur Caplan and Robert Bazell in Time:

The CDC just announced new guidelines for “critical” employees to return to work after possible COVID-19 exposure. Take your temperature often. Wear a mask. Stay 6 ft. away from others when possible. Go home if you feel sick. It is well-intentioned advice. But it is not enough—not for “critical” workers, however defined, or for the rest of us.

Until we have a vaccine, which is likely a year or more off, or truly effective treatments, which may be just as far in the future, the answer is, as it has been since the start of this pandemic: testing, testing and more testing. “Anyone who wants a test can get a test,” President Trump famously proclaimed on March 6. We know how horribly wrong he was. A tragic, preventable combination of errors in the White House, the CDC and FDA kept this country from having tests to detect the new coronavirus as it spread through the population almost unnoticed. By March 6, when Trump insisted America had sufficient testing for all of us, fewer than 2,000 Americans had gotten a test. The testing situation is improving. By April 14, around 3 million Americans had gotten COVID-19 tests, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Tests are becoming easier to access. The Department of Health and Human Services just promulgated rules allowing tests to be administered in pharmacies, and its civil rights division said it would not enforce HIPAA rules to allow more widespread community testing. Gates Ventures is funding a demonstration project that can deliver and pick up testing material for homes in the Seattle area. Abbott Labs won FDA approval for a test that can deliver results in less than 15 minutes.

“Every minute enough plastic is dumped into the world’s oceans to fill an entire dump truck. At least as much again ends up in landfill sites, and the amounts are constantly increasing. Because we love plastic. It’s handy and cheap. We produce and use twenty times as much plastic every year now as we did fifty years ago, and less than 10 percent of it is recycled. The rest of the plastic waste ends up in landfills, in roadside ditches, or in the sea. A report issued by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimated that if this continues the sea will contain more plastic than fish by 2050. This is because plastic biodegrades extremely slowly in the natural environment. So the discovery that a number of insects can digest and break down plastic is something of a sensation.

“Every minute enough plastic is dumped into the world’s oceans to fill an entire dump truck. At least as much again ends up in landfill sites, and the amounts are constantly increasing. Because we love plastic. It’s handy and cheap. We produce and use twenty times as much plastic every year now as we did fifty years ago, and less than 10 percent of it is recycled. The rest of the plastic waste ends up in landfills, in roadside ditches, or in the sea. A report issued by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimated that if this continues the sea will contain more plastic than fish by 2050. This is because plastic biodegrades extremely slowly in the natural environment. So the discovery that a number of insects can digest and break down plastic is something of a sensation. Over the past few days, I’ve been reading the major plans for what comes after social distancing. You can read them, too. There’s one from the right-leaning

Over the past few days, I’ve been reading the major plans for what comes after social distancing. You can read them, too. There’s one from the right-leaning

Fedorov’s ambition was not limited to those still living. He imagined resurrecting every person who had ever lived. Inverting the idea of the duty of the living to future generations, he argued that we owe a “resurrectory debt” to our parents, and he insisted that as technology advanced, we would pay off this debt by piecing our families back together from bones and even specks of dust. (A crackpot visionary rather than a scientist, he was short on specifics about how we might do this.) To solve the problem of housing the vast resurrected population, he looked to space, proposing the colonization of the galaxy—a hope shared by people like Thiel and Elon Musk today. But Fedorov imagined the work and benefits of immortality as collective and universal. He accumulated a number of followers during his lifetime and after his death, and his reputation as an eccentric visionary endures in Russia.

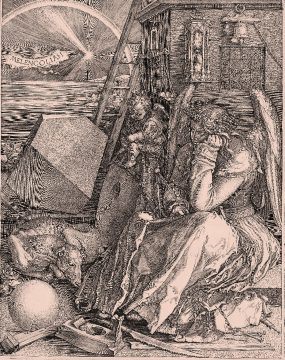

Fedorov’s ambition was not limited to those still living. He imagined resurrecting every person who had ever lived. Inverting the idea of the duty of the living to future generations, he argued that we owe a “resurrectory debt” to our parents, and he insisted that as technology advanced, we would pay off this debt by piecing our families back together from bones and even specks of dust. (A crackpot visionary rather than a scientist, he was short on specifics about how we might do this.) To solve the problem of housing the vast resurrected population, he looked to space, proposing the colonization of the galaxy—a hope shared by people like Thiel and Elon Musk today. But Fedorov imagined the work and benefits of immortality as collective and universal. He accumulated a number of followers during his lifetime and after his death, and his reputation as an eccentric visionary endures in Russia. ACCORDING TO AN ANCIENT TEXT attributed to Aristotle, black bile “can induce paralysis or torpor or depression or anxiety when it prevails in the body; but if it is overheated it produces cheerfulness, bursting into song, and ecstasies and the eruption of sores and the like.” Such “fits of exaltation” were believed to be conducive to creative achievement. “Maracus, the Syracusan,” the text tells us, “was actually a better poet when he was out of his mind.” The aesthetes of the Renaissance and the Romantic era were equally convinced of the natural link between melancholy and creativity. In As You Like It, Shakespeare’s philosophical idler Jaques, savoring his own moodiness, boasts, “I can suck melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs.” To this day, the notion persists that spleen, ennui, depression, and even madness might be correlated with genius—or, at the very least, with an artistic sensibility.

ACCORDING TO AN ANCIENT TEXT attributed to Aristotle, black bile “can induce paralysis or torpor or depression or anxiety when it prevails in the body; but if it is overheated it produces cheerfulness, bursting into song, and ecstasies and the eruption of sores and the like.” Such “fits of exaltation” were believed to be conducive to creative achievement. “Maracus, the Syracusan,” the text tells us, “was actually a better poet when he was out of his mind.” The aesthetes of the Renaissance and the Romantic era were equally convinced of the natural link between melancholy and creativity. In As You Like It, Shakespeare’s philosophical idler Jaques, savoring his own moodiness, boasts, “I can suck melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs.” To this day, the notion persists that spleen, ennui, depression, and even madness might be correlated with genius—or, at the very least, with an artistic sensibility. For Anatol Lieven, one battle has been won but now begins the hundred years’ war. In Climate Change and the Nation State, he presumes that the climate change deniers have been vanquished and have largely fled the field. So he dismisses their case. He starts from the proposition that this debate has been won. Lieven is impatient to engage in the real struggle, the civilisational war for survival. And indeed, on cue, floods in the UK and bushfires in Australia and California appear to confirm the urgency of the situation. The weather and the waters are moving. We face extraordinary challenges.

For Anatol Lieven, one battle has been won but now begins the hundred years’ war. In Climate Change and the Nation State, he presumes that the climate change deniers have been vanquished and have largely fled the field. So he dismisses their case. He starts from the proposition that this debate has been won. Lieven is impatient to engage in the real struggle, the civilisational war for survival. And indeed, on cue, floods in the UK and bushfires in Australia and California appear to confirm the urgency of the situation. The weather and the waters are moving. We face extraordinary challenges. We’re doomed’: a common refrain in casual conversation about climate change. It signals an awareness that we cannot, strictly speaking, avert climate change. It is already here. All we can hope for is to minimise climate change by keeping global average temperature changes to less than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in order to avoid rending consequences to global civilisation. It is still physically possible, says the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in a 2018 special

We’re doomed’: a common refrain in casual conversation about climate change. It signals an awareness that we cannot, strictly speaking, avert climate change. It is already here. All we can hope for is to minimise climate change by keeping global average temperature changes to less than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in order to avoid rending consequences to global civilisation. It is still physically possible, says the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in a 2018 special  Fifty years since their dissolution in April 1970 the Beatles live on. The band’s music, their significance and their individual personalities exert a hold on the cultural consciousness that seems to tighten as their heyday recedes. But is there anything new to say? Craig Brown’s

Fifty years since their dissolution in April 1970 the Beatles live on. The band’s music, their significance and their individual personalities exert a hold on the cultural consciousness that seems to tighten as their heyday recedes. But is there anything new to say? Craig Brown’s  Saving the world’s agricultural soils is perhaps the most overlooked environmental challenge of this century. Driving through freshly tilled fields in rural Indiana a few years back, I was struck by how low points retained rich, black earth, yet on the hilltops, the khaki subsoil was completely exposed. I could see the land being shorn of fertility. We urgently need to pay attention to practices that can help to regenerate it. To that end, former columnist for The New York Times Stephen Heyman resurrects an obscure figure from US agricultural history in this engaging biography, The Planter of Modern Life. Heyman’s subject, Louis Bromfield, was a Pulitzer-prizewinning novelist before he became a prominent critic of industrialized farming. Today, Bromfield’s journey of discovery reinforces growing calls to rebuild healthy, fertile soil around the world.

Saving the world’s agricultural soils is perhaps the most overlooked environmental challenge of this century. Driving through freshly tilled fields in rural Indiana a few years back, I was struck by how low points retained rich, black earth, yet on the hilltops, the khaki subsoil was completely exposed. I could see the land being shorn of fertility. We urgently need to pay attention to practices that can help to regenerate it. To that end, former columnist for The New York Times Stephen Heyman resurrects an obscure figure from US agricultural history in this engaging biography, The Planter of Modern Life. Heyman’s subject, Louis Bromfield, was a Pulitzer-prizewinning novelist before he became a prominent critic of industrialized farming. Today, Bromfield’s journey of discovery reinforces growing calls to rebuild healthy, fertile soil around the world. In the third week of March, while most of our minds were fixed on surging coronavirus death rates and the apocalyptic scenes in hospital wards, global financial markets came as close to a collapse as they have since September 2008. The price of shares in the world’s major corporations plunged. The value of the dollar surged against every currency in the world, squeezing debtors everywhere from Indonesia to Mexico. Trillion-dollar markets for government debt, the basic foundation of the financial system, lurched up and down in terror-stricken cycles.

In the third week of March, while most of our minds were fixed on surging coronavirus death rates and the apocalyptic scenes in hospital wards, global financial markets came as close to a collapse as they have since September 2008. The price of shares in the world’s major corporations plunged. The value of the dollar surged against every currency in the world, squeezing debtors everywhere from Indonesia to Mexico. Trillion-dollar markets for government debt, the basic foundation of the financial system, lurched up and down in terror-stricken cycles. In contrast with other genres in literature, in crime fiction, which mainly started in the mid-19th century, women writers (and even women sleuths) became active around the same time as male writers and sleuths in their stories. By some accounts around the middle of 1860’s, both the first modern detective novels (by female as well as male writers in US, UK and France) and the first professional female detectives in them (one Mrs. G— in one case, Mrs. Paschal in another, both working for the British police) appeared. Most of us, of course, are more familiar with characters in the Golden Age of crime fiction of the 1920’s and the 1930’s, particularly, Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple and Dorothy Sayers’ Harriet Vane. The number of female writers and sleuths has proliferated in recent decades. It goes without saying that not all of the female crime novelists come out as feminists, and that some male writers can do feminist crime novels quite well.

In contrast with other genres in literature, in crime fiction, which mainly started in the mid-19th century, women writers (and even women sleuths) became active around the same time as male writers and sleuths in their stories. By some accounts around the middle of 1860’s, both the first modern detective novels (by female as well as male writers in US, UK and France) and the first professional female detectives in them (one Mrs. G— in one case, Mrs. Paschal in another, both working for the British police) appeared. Most of us, of course, are more familiar with characters in the Golden Age of crime fiction of the 1920’s and the 1930’s, particularly, Agatha Christie’s Miss Jane Marple and Dorothy Sayers’ Harriet Vane. The number of female writers and sleuths has proliferated in recent decades. It goes without saying that not all of the female crime novelists come out as feminists, and that some male writers can do feminist crime novels quite well.

Sughra Raza. Untitled; Arnold Arboretum, Boston, March, 2020.

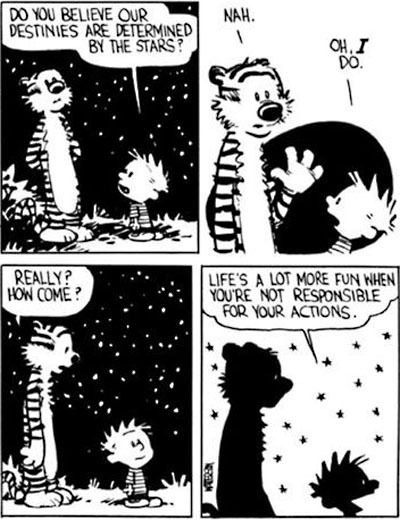

Sughra Raza. Untitled; Arnold Arboretum, Boston, March, 2020. The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy):

The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy): What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher