Month: April 2020

A Japanese Literary Star Joins Her Peers on Western Bookshelves

Mieko Kawakami at the NYT:

For decades, Haruki Murakami defined contemporary Japanese literature for the Anglophone reader. In such bona fide masterpieces as “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle” and “A Wild Sheep Chase,” the author created a surreal world of talking sheep and lost cats, jazz bars and manic pixie dream girls.

For decades, Haruki Murakami defined contemporary Japanese literature for the Anglophone reader. In such bona fide masterpieces as “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle” and “A Wild Sheep Chase,” the author created a surreal world of talking sheep and lost cats, jazz bars and manic pixie dream girls.

But in the decades since the publication of those novels, Murakami’s tropes haven’t always aged well. In particular, his depictions of women have seemed, at least to some of us, troublingly thin. As his oeuvre kept proliferating, it sometimes felt as if the Murakami machine were eating up what limited oxygen there was for Japanese fiction in translation.

Thankfully, of late, a number of female writers have stepped out from the Murakami shadow and into English translation.

more here.

Vernon Subutex 1

Nadja Spiegelman at the NYRB:

Underlying all of Despentes’s work is the concept of rape. It is the omnipresent possibility through which everything is refracted. There’s a war going on, her books insist, not so much between men and women as on men and women, waged through the constructs of gender. Masculinity, for Despentes, is the artillery that tears our bodies apart, while femininity is the drug of mass indoctrination. What she had learned from punk rock, she once said, was to look clearly at the world and declare it rotten.

Underlying all of Despentes’s work is the concept of rape. It is the omnipresent possibility through which everything is refracted. There’s a war going on, her books insist, not so much between men and women as on men and women, waged through the constructs of gender. Masculinity, for Despentes, is the artillery that tears our bodies apart, while femininity is the drug of mass indoctrination. What she had learned from punk rock, she once said, was to look clearly at the world and declare it rotten.

In the 1990s French literature was breaking open, and the literary scene was making room for postcolonial writers, provocateurs (notably Michel Houellebecq), and women (notably women who, writing frankly about sex and desire, were also deemed provocateurs). Twenty-seven-year-old Marie Darrieussecq’s Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation (1996), a fable narrated by a woman who slowly transforms into a pig, was, in the author’s words, about “the metamorphosis of a female object into a conscious woman.”

more here.

Mirror Images

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

MY TWIN BROTHER IS A DOCTOR. We celebrated our birthday this past Tuesday, April 7: our first one with me in quarantine. He is in California, working the frontlines of the war against COVID-19. I am sequestered by a lake in Indiana; my chronic lung disease, a complication of rheumatoid arthritis, makes me especially vulnerable to the virus. The most frequent question twins get is “What it is like to be a twin?” It is also the most difficult question for us to answer. We are born and develop in such an intertwined way that it is impossible for us to imagine what it would be like not to have a twin. We cannot trace the genealogy of our implicit division of labor; when did we reach an agreement that I would be the talkative one? When did we decide that he would be the protective one? And when did we agree to be equally excitable people? We couldn’t tell you because we do not know. It is just the way it is, the way we are.

MY TWIN BROTHER IS A DOCTOR. We celebrated our birthday this past Tuesday, April 7: our first one with me in quarantine. He is in California, working the frontlines of the war against COVID-19. I am sequestered by a lake in Indiana; my chronic lung disease, a complication of rheumatoid arthritis, makes me especially vulnerable to the virus. The most frequent question twins get is “What it is like to be a twin?” It is also the most difficult question for us to answer. We are born and develop in such an intertwined way that it is impossible for us to imagine what it would be like not to have a twin. We cannot trace the genealogy of our implicit division of labor; when did we reach an agreement that I would be the talkative one? When did we decide that he would be the protective one? And when did we agree to be equally excitable people? We couldn’t tell you because we do not know. It is just the way it is, the way we are.

…This birthday was different. Separated by thousands of miles, we are both fighting battles. He is in harm’s way, diagnosing and treating patients. I am sequestered more strictly than most and likely much longer than most. I know that I have a truly terrible chance of surviving COVID-19, were I to contract it. Both of us live in the constant unrelenting paranoia that we could have been exposed, or endangered others, in different ways. I worry constantly and crazily about him, and he does the same for me.

So I thought hard about what to get him this year. I wanted it to be special, something he could not get or would not get for himself. Everything I could think of—framed pictures of us, fruit, cheese, our favorite snacks, cologne, clothes—all seemed banal against the high drama of the moment: a birthday falling in what the news is calling “peak death week.” All of these thoughts swam lazily in my head when I opened my medicine cabinet to take my medication. Like so many other patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus, I take hydroxychloroquine, or Plaquenil, to control disease progression. When I began taking it years ago, I never dreamed of a day that the name would be all over the news, and even peddled by America’s reality-star president.

When I heard about hydroxychloroquine’s possible effectiveness in treating COVID-19, I immediately called my brother. I wanted him to get some for himself. Like many doctors, he was unconvinced: a few small studies, with very mixed results. His only concern was that I should have enough of the drug to take myself. Because he was so worried, I called my pharmacist to insure that my prescription could be filled. Days before the president announced his “feeling” that it was a potential cure and the drug became unavailable to many patients like me, my pharmacist filled a three-month prescription.

I do not believe the president when he says hydroxychloroquine is a cure or even a treatment for COVID-19.

More here.

With Each Briefing, Trump Is Making Us Worse People

Tom Nichols in The Atlantic:

There has never been an American president as spiritually impoverished as Donald Trump. And his spiritual poverty, like an overdrawn checking account that keeps imposing new penalties on a customer already in difficult straits, is draining the last reserves of decency among us at a time when we need it most. I do not mean that Trump is the least religious among our presidents, though I have no doubt that he is; as the scholar Stephen Knott pointed out, Trump has shown “a complete lack of religious sensibility” unique among American presidents. (Just recently he wished Americans a “Happy Good Friday,” which suggests that he is unaware of the meaning of that day.) Nor do I mean that Trump is the least-moral president we’ve ever had, although again, I am certain that he is. John F. Kennedy was, in theory, a practicing Catholic, but he swam in a pool of barely concealed adultery in the White House. Richard Nixon was a Quaker, but one who attempted to subvert the Constitution. Andrew Johnson showed up pig-drunk to his inauguration. Trump’s manifest and immense moral failures—and the shameless pride he takes in them—make these men seem like amateurs by comparison. And finally, I do not mean that Trump is the most unstable person ever to occupy the Oval Office, although he is almost certain to win that honor as well. As Peter Wehner has eloquently put it, Trump has an utterly disordered personality. Psychiatrists can’t help but diagnose Trump, even if it’s in defiance of the old Goldwater Rule against such practices. I know mental-health professionals who agree with George Conway and others that Trump is a malignant narcissist.

There has never been an American president as spiritually impoverished as Donald Trump. And his spiritual poverty, like an overdrawn checking account that keeps imposing new penalties on a customer already in difficult straits, is draining the last reserves of decency among us at a time when we need it most. I do not mean that Trump is the least religious among our presidents, though I have no doubt that he is; as the scholar Stephen Knott pointed out, Trump has shown “a complete lack of religious sensibility” unique among American presidents. (Just recently he wished Americans a “Happy Good Friday,” which suggests that he is unaware of the meaning of that day.) Nor do I mean that Trump is the least-moral president we’ve ever had, although again, I am certain that he is. John F. Kennedy was, in theory, a practicing Catholic, but he swam in a pool of barely concealed adultery in the White House. Richard Nixon was a Quaker, but one who attempted to subvert the Constitution. Andrew Johnson showed up pig-drunk to his inauguration. Trump’s manifest and immense moral failures—and the shameless pride he takes in them—make these men seem like amateurs by comparison. And finally, I do not mean that Trump is the most unstable person ever to occupy the Oval Office, although he is almost certain to win that honor as well. As Peter Wehner has eloquently put it, Trump has an utterly disordered personality. Psychiatrists can’t help but diagnose Trump, even if it’s in defiance of the old Goldwater Rule against such practices. I know mental-health professionals who agree with George Conway and others that Trump is a malignant narcissist.

What I mean instead is that Trump is a spiritual black hole. He has no ability to transcend himself by so much as an emotional nanometer. Even narcissists, we are told by psychologists, have the occasional dark night of the soul. They can recognize how they are perceived by others, and they will at least pretend to seek forgiveness and show contrition as a way of gaining the affection they need. They are capable of infrequent moments of reflection, even if only to adjust strategies for survival. Trump’s spiritual poverty is beyond all this. He represents the ultimate triumph of a materialist mindset. He has no ability to understand anything that is not an immediate tactile or visual experience, no sense of continuity with other human beings, and no imperatives more important than soothing the barrage of signals emanating from his constantly panicked and confused autonomic system.

The humorist Alexandra Petri once likened Trump to a goldfish, a purely reactive animal lost in a “pastless, futureless, contextless void.” This is an apt comparison, with one major flaw: Goldfish are not malevolent, and do not corrode the will and decency of those who gaze on them.

More here.

The World After Coronavirus: The Future Of Neoliberalism – Adil Najam Interviews Noam Chomsky, Part 2

The Normal Economy Is Never Coming Back

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

As the coronavirus lockdown began, the first impulse was to search for historical analogies—1914, 1929, 1941? As the weeks have ground on, what has come ever more to the fore is the historical novelty of the shock that we are living through. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, America’s economy is now widely expected to shrink by a quarter. That is as much as during the Great Depression. But whereas the contraction after 1929 stretched over a four-year period, the coronavirus implosion will happen over the next three months. There has never been a crash landing like this before. There is something new under the sun. And it is horrifying.

As the coronavirus lockdown began, the first impulse was to search for historical analogies—1914, 1929, 1941? As the weeks have ground on, what has come ever more to the fore is the historical novelty of the shock that we are living through. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, America’s economy is now widely expected to shrink by a quarter. That is as much as during the Great Depression. But whereas the contraction after 1929 stretched over a four-year period, the coronavirus implosion will happen over the next three months. There has never been a crash landing like this before. There is something new under the sun. And it is horrifying.

As recently as five weeks ago, at the beginning of March, U.S. unemployment was at record lows. By the end of March, it had surged to somewhere around 13 percent. That is the highest number recorded since World War II. We don’t know the precise figure because our system of unemployment registration was not built to track an increase at this speed. On successive Thursdays, the number of those making initial filings for unemployment insurance has surged first to 3.3 million, then 6.6 million, and now by another 6.6 million. At the current rate, as the economist Justin Wolfers pointed out in the New York Times, U.S. unemployment is rising at nearly 0.5 percent per day. It is no longer unimaginable that the overall unemployment rate could reach 30 percent by the summer.

More here.

The World After Coronavirus: The Future of Neoliberalism – Adil Najam interviews Noam Chomsky

The Coronavirus Is a Preview of Our Climate-Change Future

David Wallace-Wells in New York Magazine:

Nature is mighty, and scary, and we have not defeated it but live within it, subject to its temperamental power, no matter where it is that you live or how protected you may normally feel. As the coronavirus has paralyzed much of the northern hemisphere, for instance, 192 billion locusts, perhaps 8,000 times more than usual, are swarming East Africa in clouds as big as whole cities, thanks to weather patterns scrambled by climate change; a small swarm can destroy the food supply of 35,000 people in a single day, and they are now traveling in swathes as wide as 25 miles, imperiling the food supply of tens of millions. In the U.S., it looks likely we will now be sheltering in place into the beginning of hurricane season. “We have been living in a bubble, a bubble of false comfort and denial,” as George Monbiot wrote recently in the Guardian. “Living behind screens, passing between capsules — our houses, cars, offices and shopping malls — we persuaded ourselves that contingency had retreated, that we had reached the point all civilisations seek: insulation from natural hazards.”

Nature is mighty, and scary, and we have not defeated it but live within it, subject to its temperamental power, no matter where it is that you live or how protected you may normally feel. As the coronavirus has paralyzed much of the northern hemisphere, for instance, 192 billion locusts, perhaps 8,000 times more than usual, are swarming East Africa in clouds as big as whole cities, thanks to weather patterns scrambled by climate change; a small swarm can destroy the food supply of 35,000 people in a single day, and they are now traveling in swathes as wide as 25 miles, imperiling the food supply of tens of millions. In the U.S., it looks likely we will now be sheltering in place into the beginning of hurricane season. “We have been living in a bubble, a bubble of false comfort and denial,” as George Monbiot wrote recently in the Guardian. “Living behind screens, passing between capsules — our houses, cars, offices and shopping malls — we persuaded ourselves that contingency had retreated, that we had reached the point all civilisations seek: insulation from natural hazards.”

COVID-19 is one such hazard we believed, until a few weeks ago, we were mostly invulnerable to. In the future, we may have to reckon also with diseases we believed we already defeated, since in addition to bringing about pandemics of the future, global warming will revive plagues of the past.

More here.

Disturbed: The Sound of Silence

I know you know this song but listen to this version to the end anyway. 🙂

Hildegard von Bingen – Celestial Harmonies Responsories and Antiphons

Homage to Albert Murray

Clifford Thompson at The Baffler:

And then I read The Omni-Americans, Murray’s first book, originally published in 1970 and now reissued in a fiftieth-anniversary edition by the Library of America. It would be difficult to overstate the impact that this essay collection, especially the title essay, had on my life. The Omni-Americans made it clear that American blacks and whites (and Americans of Asian, Native, and Latinx descent, too) are unlike people anywhere else in that they have, however little any number of them may want to admit it, comingled, both physically and culturally, to the extent that the nation is, in Murray’s words, “incontestably mulatto.” Black culture is of course a central part of this mix, and what I took from the book was that there was no place in America a black person could go—even if there were places that person wouldn’t particularly want to go—and not still be among his or her or their own.

And then I read The Omni-Americans, Murray’s first book, originally published in 1970 and now reissued in a fiftieth-anniversary edition by the Library of America. It would be difficult to overstate the impact that this essay collection, especially the title essay, had on my life. The Omni-Americans made it clear that American blacks and whites (and Americans of Asian, Native, and Latinx descent, too) are unlike people anywhere else in that they have, however little any number of them may want to admit it, comingled, both physically and culturally, to the extent that the nation is, in Murray’s words, “incontestably mulatto.” Black culture is of course a central part of this mix, and what I took from the book was that there was no place in America a black person could go—even if there were places that person wouldn’t particularly want to go—and not still be among his or her or their own.

more here.

The Beatles in Time

Dominic Green at Literary Review:

If a German raid had not compelled Jim McCartney and Mary Mohin to get to know each other better, would Paul McCartney have been born? If Paul had passed his Latin O level, he wouldn’t have stayed down a year, befriended George Harrison and introduced him to John Lennon. Would any of us be the same if Ringo had never emerged from a ten-week coma as a child, or if his grandmother hadn’t then forced him to write with his right hand instead of naturally with his left, which gave his drumming ‘the idiosyncratic style that countless Beatles tribute acts still find hard to duplicate’? When Lennon beats up Bob Wooler, MC at the Cavern, for calling him a ‘bloody queer’, Brown provides fourteen differing accounts of what happened, four from Lennon himself. A similar chorus speculates on whether Lennon and Brian Epstein had sex, with Brown again providing differing accounts from Lennon, and Yoko adding that she thought John fancied Paul.

If a German raid had not compelled Jim McCartney and Mary Mohin to get to know each other better, would Paul McCartney have been born? If Paul had passed his Latin O level, he wouldn’t have stayed down a year, befriended George Harrison and introduced him to John Lennon. Would any of us be the same if Ringo had never emerged from a ten-week coma as a child, or if his grandmother hadn’t then forced him to write with his right hand instead of naturally with his left, which gave his drumming ‘the idiosyncratic style that countless Beatles tribute acts still find hard to duplicate’? When Lennon beats up Bob Wooler, MC at the Cavern, for calling him a ‘bloody queer’, Brown provides fourteen differing accounts of what happened, four from Lennon himself. A similar chorus speculates on whether Lennon and Brian Epstein had sex, with Brown again providing differing accounts from Lennon, and Yoko adding that she thought John fancied Paul.

more here.

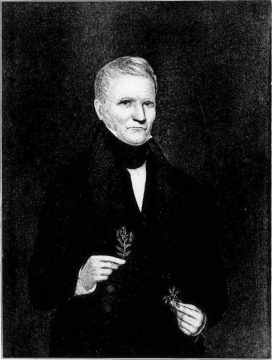

The 19th Century Roots of Modern Medical Denialism

John Charpentier in Undark:

MIRACLE CURES, detox cleanses, and vaccine denial may seem to be the products of Hollywood and the social media age, but the truth is that medical pseudoscience has been a cultural touchstone in the U.S. since nearly its founding. At the dawn of the 19th century, when medical journals were still written almost entirely in Latin and only a handful of medical schools existed in the country, the populist fervor that animated the Revolutionary War came to the clinic. And while there was no shortage of cranks peddling phony medicine on a raft of dubious conspiracy theories in the early 1800s, none was more successful and celebrated than Samuel Thomson.

MIRACLE CURES, detox cleanses, and vaccine denial may seem to be the products of Hollywood and the social media age, but the truth is that medical pseudoscience has been a cultural touchstone in the U.S. since nearly its founding. At the dawn of the 19th century, when medical journals were still written almost entirely in Latin and only a handful of medical schools existed in the country, the populist fervor that animated the Revolutionary War came to the clinic. And while there was no shortage of cranks peddling phony medicine on a raft of dubious conspiracy theories in the early 1800s, none was more successful and celebrated than Samuel Thomson.

Portraying himself as an illiterate pig farmer (he was neither), Thomson barnstormed the Northeast telling rapt audiences things they wanted to hear: that “natural” remedies were superior to toxic “chemical” drugs; that all disease had a single cause, despite its many manifestations; that intuition and divine providence had guided him to botanical panaceas; that corrupt medical elites, blinded by class condescension and education, were persecuting him, a humble, ordinary man, because of the threat his ideas and discoveries posed to their profits. For decades, Thomson peddled his dubious system of alternative medicine to Americans by playing to their cultural, political, and religious identities. Two centuries later, the era of Thomsonian medicine isn’t just a historical curiosity; it continues to provide a playbook for grifters and dissembling politicians peddling pseudoscientific solutions to everything from cancer to Covid-19.

More here.

Can a Battery of New COVID Tests Stem the US Debacle?

Robert Bazell in Nautilus:

Can we leap beyond flattening the curve and eliminate COVID-19 as a public health threat—not years from now but weeks? “It’s a war we should fight to win,” declared Harvey V. Fineberg, former Dean of the Harvard School of Public Health, in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 War metaphors applied to health—“War on Drugs,” “War on Cancer”—are tiresome and often counterproductive. But considering the attempt to overcome COVID-19, the metaphor could not be more apt. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of lives are at risk. The economy of much of the world depends on the outcome. If it’s improperly managed, the effort to contain the pandemic could drag on for months or years longer than necessary. As in all wars, the battles are complex, varied and ever-changing. High priority must go to health care workers to get them personal protective equipment, ventilators, and all the tools they need. Efforts to develop effective treatments and a protective vaccine must proceed with maximum haste.

Can we leap beyond flattening the curve and eliminate COVID-19 as a public health threat—not years from now but weeks? “It’s a war we should fight to win,” declared Harvey V. Fineberg, former Dean of the Harvard School of Public Health, in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 War metaphors applied to health—“War on Drugs,” “War on Cancer”—are tiresome and often counterproductive. But considering the attempt to overcome COVID-19, the metaphor could not be more apt. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of lives are at risk. The economy of much of the world depends on the outcome. If it’s improperly managed, the effort to contain the pandemic could drag on for months or years longer than necessary. As in all wars, the battles are complex, varied and ever-changing. High priority must go to health care workers to get them personal protective equipment, ventilators, and all the tools they need. Efforts to develop effective treatments and a protective vaccine must proceed with maximum haste.

The first battlefield to be joined in an encounter with a new pathogen is medical testing. On this front, the United States lost miserably. The White House, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Food and Drug Administration, failed to identify those who are infected so they and their contacts can be isolated, possibly stopping the epidemic before it spreads. It was the Pearl Harbor of COVID-19. But like the real defeat in World War II, it is only one battle. The disaster can mobilize the U.S. to triumph, provided it has learned from its mistakes, and now acts with alacrity on the best information. This is starting to happen, but not quickly enough. Public health officials across the country still decry a massive shortage of tests. Only a portion of people told they have COVID-19 get tested. On Monday, Chrissie Juliano, executive director of the Big Cities Health Coalition, which represents 30 urban public health departments, told The New York Times, “Many local communities are flying blind, making decisions in the absence of full information largely due to the failure of the federal government to provide sufficient testing capacity.”

More here.

Friday Poem

Serpent Dialogues (Extract)

When the woman realised the snake was scared of her too, she went back to the balcony, where she’d at first mistaken him for a spool of brightly-coloured rope. She lay down on the ground there and waited, watching as fear took hold of her body: whirlpools of sickness through her limbs, sweat like black ice, her breath sprinting ahead of her and her inability to catch up . She kept wanting to flee, her ears full of fabricated rattle-hiss, but she remembered the way he’d flashed out of sight, back into the encroaching wilderness as soon as she’d taken a step too close. The thought of the snake being afraid somehow helped her stay put till lunch . He did not come back that day, but she decided to repeat the ritual every morning at the same hour. To give him time, even if he needed a thousand years, allowing him to make all the decisions. She lay always in the same spot, on her side, still as a mountain, her hip pointy as a snowy peak . The snake watched sideways, from a safe distance, and slinked a little closer each day, trying to work out if the woman was a threat.

A long time passed before she was able even to unclench her jaw and allow sound to come out. When she finally did, she asked all manner of absurd questions, and the snake, to her surprise, responded.

WOMAN: Snake, what do you think of monotheism? Since everything is holy, I mean

SNAKE: Men – humans – need to organize everything. Messages need to be packaged in an intelligible way for them, otherwise they’d be lost

W: That’s why the Mass is didactic in structure, like a theatre play, is what you’re saying

S: Yes, but the sacred element is also built through repetition. Repetition is much loved by men

W: You don’t dislike it either, since you come here to see me every day

S: It’s nice on this rock

W: There are countless others to choose from

S: What about you, why are you here every morning?

W: Gives me a good vantage point .

by Juana Adcock

From: Split

Blue Diode Press, Leith, Scotland, 2019

Amsterdam to embrace ‘doughnut’ model to mend post-coronavirus economy

Daniel Boffey in The Guardian:

A doughnut cooked up in Oxford will guide Amsterdam out of the economic mess left by the coronavirus pandemic.

A doughnut cooked up in Oxford will guide Amsterdam out of the economic mess left by the coronavirus pandemic.

While straining to keep citizens safe in the Dutch capital, municipality officials and the British economist Kate Raworth from Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute have also been plotting how the city will rebuild in a post-Covid-19 world.

The conclusion? Out with the global attachment to economic growth and laws of supply and demand, and in with the so-called doughnut model devised by Raworth as a guide to what it means for countries, cities and people to thrive in balance with the planet.

Raworth’s 2017 bestselling book, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, has graced the bedside table of people ranging from the former Brexit secretary David Davis to the Guardian columnist George Monbiot, who described it as a “breakthrough alternative to growth economics”.

More here.

Rilke’s Legacy: Laura La Rosa on Writing

Laura La Rosa in the Sydney Review of Books:

Growing up, ours was a typical post-eighties Western Sydney household: instant cuppas, Wonder White, three channels and the Daily Tele. We were Blackfellas on my mother’s side and working class migrant Italian farmers on my father’s. We survived, just, but the arts were as foreign to me as the city was.

Growing up, ours was a typical post-eighties Western Sydney household: instant cuppas, Wonder White, three channels and the Daily Tele. We were Blackfellas on my mother’s side and working class migrant Italian farmers on my father’s. We survived, just, but the arts were as foreign to me as the city was.

I remember the day we got dial-up internet. I was fourteen. By then, my brother had been shafted to a caravan out the back, with mum claiming the third bedroom as her office where she ran a small cleaning supplies business. She studied bookkeeping and built herself a website. Her then-husband bailed her out financially more than once; even so her efforts to harness late-nineties innovation were a feat for a suburban mum.

By the time I was seventeen, I had been kicked out of school and home. I went to TAFE and studied business management, surviving through clerical work and progressing from friend’s couches to a granny flat rental of my own. Later, well into my twenties, I put myself through design school where I learned to think, an experience that would eventually compel me to write.

More here.

The psychology behind a pandemic: Interview with Steven Pinker

COVID-19 and the Global Economy

John Feffer in Inference Review:

THE MODERN GLOBAL economy rests on the foundation of modern medicine. The transactions that sustain the global trade of goods and services require an implicit assurance that merchants and financiers are not infecting one another when they meet to conduct business. Economic globalization requires that the nodes of international distribution—ports, airline terminals, railway stations, intermodal hubs—do not function as distribution points for pathogens. Otherwise, the transaction costs in disrupted operations, emergency health care, and labor turnover would outweigh overseas investment, and resources would stay closer to home.

THE MODERN GLOBAL economy rests on the foundation of modern medicine. The transactions that sustain the global trade of goods and services require an implicit assurance that merchants and financiers are not infecting one another when they meet to conduct business. Economic globalization requires that the nodes of international distribution—ports, airline terminals, railway stations, intermodal hubs—do not function as distribution points for pathogens. Otherwise, the transaction costs in disrupted operations, emergency health care, and labor turnover would outweigh overseas investment, and resources would stay closer to home.

Before the modern era, global transactions in the marketplace or around the field of battle carried a significant risk of infection. The global circulation of pathogens, hitching a ride on explorers, soldiers, and traders, has periodically devastated civilizations. Plagues played a role in undermining the Roman Empire. Disease carried by the conquistadors devastated indigenous communities throughout the Americas. The influenza outbreak at the end of World War I was the final factor in suppressing the first wave of modern economic globalization, which had gathered force at the beginning of the twentieth century thanks to the telegraph, railroads, and modern shipping.

More here.