Month: April 2020

The World of The Dardenne Brothers

Lydia Wilson at the TLS:

This close framing, at times claustrophobic, often anxiety-provoking, is key to all the films made by the Dardenne brothers, Luc and Jean-Pierre. The Son, too, opens by closely tracking the protagonist, Olivier, so we almost see what he does; we can observe Olivier’s desperation to see, to spy, but we don’t quite know what or who or why. Tension is established and maintained, but not for its own sake: “Finding the ‘wrong place’ for the camera”, says Luc in his diaries, On the Back of Our Images, Volume 1 (translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman and Sammi Skolmoski), “is our way of creating the secret for the viewer all while bestowing the secret, and consequently an existence, upon our characters.”

more here.

Simone de Beauvoir

Joanna Biggs at the LRB:

But since April 1986, when Beauvoir died, the idea of her as a feminist heroine has faded. Her letters to Sartre, published four years later, showed her seducing her pupils and then passing them on to Sartre, in a bad modernist version of Les Liaisons dangereuses. She carried on a ten-year affair with the husband of one of her female lovers without the woman knowing. The publication of her letters to Nelson Algren in 1997 made the relationship she had with Sartre look passionless, as did the photo that emerged in 2008 of Beauvoir at 42, pinning her hair up in Algren’s bathroom wearing just a pair of heels. And her insistence that Sartre was the philosopher, not her – because she hadn’t invented a new system as he had done – looks too modest: he often took ideas from her novels, it now seems, not the other way round. The newest volume in the Illinois series of her uncollected writings shows Beauvoir at the beginning of her mythic pact with Sartre wavering between three men; the new memoir by Bair describes a cold, drunk, grumpy old woman; Kate Kirkpatrick’s biography uses the posthumous sources to show where Beauvoir was inconsistent, obfuscatory or even mendacious in her own accounts of herself.

But since April 1986, when Beauvoir died, the idea of her as a feminist heroine has faded. Her letters to Sartre, published four years later, showed her seducing her pupils and then passing them on to Sartre, in a bad modernist version of Les Liaisons dangereuses. She carried on a ten-year affair with the husband of one of her female lovers without the woman knowing. The publication of her letters to Nelson Algren in 1997 made the relationship she had with Sartre look passionless, as did the photo that emerged in 2008 of Beauvoir at 42, pinning her hair up in Algren’s bathroom wearing just a pair of heels. And her insistence that Sartre was the philosopher, not her – because she hadn’t invented a new system as he had done – looks too modest: he often took ideas from her novels, it now seems, not the other way round. The newest volume in the Illinois series of her uncollected writings shows Beauvoir at the beginning of her mythic pact with Sartre wavering between three men; the new memoir by Bair describes a cold, drunk, grumpy old woman; Kate Kirkpatrick’s biography uses the posthumous sources to show where Beauvoir was inconsistent, obfuscatory or even mendacious in her own accounts of herself.

more here.

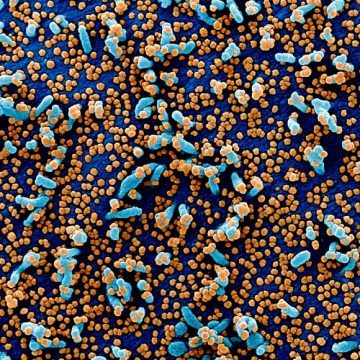

Experimental Drug Has Broad Spectrum Antiviral Activity against Multiple Coronaviruses

From Science News:

EIDD-2801 is an orally available form of the antiviral compound EIDD-1931 (β-D-N4-hydroxycytidine). It can be taken as a pill and can be properly absorbed to travel to the lungs. When given as a treatment 12 or 24 hours after infection has begun, EIDD-2801 can reduce the degree of lung damage and weight loss in mice. This window of opportunity is expected to be longer in humans, because the period between coronavirus disease onset and death is generally extended in humans compared to mice. “This new drug not only has high potential for treating COVID-19 patients, but also appears effective for the treatment of other serious coronavirus infections,” said study senior author Professor Ralph Baric, a virologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

EIDD-2801 is an orally available form of the antiviral compound EIDD-1931 (β-D-N4-hydroxycytidine). It can be taken as a pill and can be properly absorbed to travel to the lungs. When given as a treatment 12 or 24 hours after infection has begun, EIDD-2801 can reduce the degree of lung damage and weight loss in mice. This window of opportunity is expected to be longer in humans, because the period between coronavirus disease onset and death is generally extended in humans compared to mice. “This new drug not only has high potential for treating COVID-19 patients, but also appears effective for the treatment of other serious coronavirus infections,” said study senior author Professor Ralph Baric, a virologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Compared with other potential COVID-19 treatments that must be administered intravenously, EIDD-2801 can be delivered by mouth as a pill. In addition to ease of treatment, this offers a potential advantage for treating less-ill patients or for prophylaxis — for example, in a nursing home where many people have been exposed but are not yet sick. “We are amazed at the ability of EIDD-1931 and EIDD-2801 to inhibit all tested coronaviruses and the potential for oral treatment of COVID-19,” said study co-author Dr. Andrea Pruijssers, an antiviral scientist at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

In 2019, the researchers reported that EIDD-1931 blocked the replication of a broad spectrum of coronaviruses. They also performed the preclinical development of remdesivir, another antiviral drug currently in clinical trials of patients with COVID-19. In the new study, they demonstrated that viruses that show resistance to remdesivir experience higher inhibition from EIDD-1931. “Viruses that carry remdesivir resistance mutations are actually more susceptible to EIDD-1931 and vice versa, suggesting that the two drugs could be combined for greater efficacy and to prevent the emergence of resistance,” said study co-author Dr. George Painter, from Emory University and the Drug Innovation Ventures at Emory (DRIVE).

More here.

The pandemic is a portal

Arundhati Roy in Financial Times:

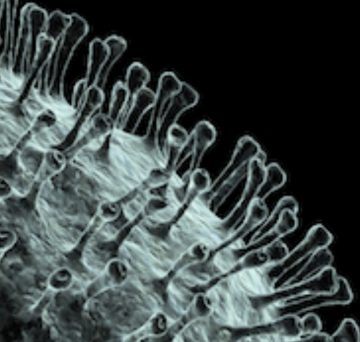

Who can use the term “gone viral” now without shuddering a little? Who can look at anything any more — a door handle, a cardboard carton, a bag of vegetables — without imagining it swarming with those unseeable, undead, unliving blobs dotted with suction pads waiting to fasten themselves on to our lungs?

Who can use the term “gone viral” now without shuddering a little? Who can look at anything any more — a door handle, a cardboard carton, a bag of vegetables — without imagining it swarming with those unseeable, undead, unliving blobs dotted with suction pads waiting to fasten themselves on to our lungs?

Who can think of kissing a stranger, jumping on to a bus or sending their child to school without feeling real fear? Who can think of ordinary pleasure and not assess its risk? Who among us is not a quack epidemiologist, virologist, statistician and prophet? Which scientist or doctor is not secretly praying for a miracle? Which priest is not — secretly, at least — submitting to science? And even while the virus proliferates, who could not be thrilled by the swell of birdsong in cities, peacocks dancing at traffic crossings and the silence in the skies? The number of cases worldwide this week crept over a million. More than 50,000 people have died already. Projections suggest that number will swell to hundreds of thousands, perhaps more. The virus has moved freely along the pathways of trade and international capital, and the terrible illness it has brought in its wake has locked humans down in their countries, their cities and their homes.

But unlike the flow of capital, this virus seeks proliferation, not profit, and has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the flow. It has mocked immigration controls, biometrics, digital surveillance and every other kind of data analytics, and struck hardest — thus far — in the richest, most powerful nations of the world, bringing the engine of capitalism to a juddering halt. Temporarily perhaps, but at least long enough for us to examine its parts, make an assessment and decide whether we want to help fix it, or look for a better engine. The mandarins who are managing this pandemic are fond of speaking of war. They don’t even use war as a metaphor, they use it literally. But if it really were a war, then who would be better prepared than the US? If it were not masks and gloves that its frontline soldiers needed, but guns, smart bombs, bunker busters, submarines, fighter jets and nuclear bombs, would there be a shortage?

More here.

Thursday Poem

Ya Lateef!

A lot more malaise and a little more grief every day,

aware that all seasons, the stormy, the sunlit, are brief every day.

I don’t know the name of the hundredth drowned child, just the names

of the oligarchs trampling the green, eating beef every day,

while luminous creatures flick, stymied, above and around

the plastic detritus that’s piling up over the reef every day.

A tiny white cup of black coffee in afternoon shade,

while an oud or a sax plays brings breath and relief every day.

Another beginning, no useful conclusion in sight‚—

another first draft that I tear out and add to the sheaf every day.

One name, three-in-one, ninety-nine, or a matrix of tales

that are one story only, well-springs of belief every day.

But I wake before dawn to read news that arrived overnight

on a minuscule screen , and exclaim Ya Lateef!* every day.

by Marilyn Hacker

from the Academy of American Poets, 4/9/2020

*Ya Lateef: Good God!

Sickness and Stoicism

Roy Wayne Meredith III in Quillette:

In less than three months, COVID-19 has changed from a peripheral concern, barely registering in presidential debates, to the greatest global crisis since World War II. We are living in extraordinary times, and there is scarcely an industry or country that has escaped the impact of the new virus. In the United States, the Federal Reserve estimates that the unemployment rate could briefly skyrocket to 32 percent—higher than anything the country experienced during the Great Depression. People have lost their livelihoods. Many others are scared about what is to come when they develop a fever or cough.

In less than three months, COVID-19 has changed from a peripheral concern, barely registering in presidential debates, to the greatest global crisis since World War II. We are living in extraordinary times, and there is scarcely an industry or country that has escaped the impact of the new virus. In the United States, the Federal Reserve estimates that the unemployment rate could briefly skyrocket to 32 percent—higher than anything the country experienced during the Great Depression. People have lost their livelihoods. Many others are scared about what is to come when they develop a fever or cough.

Illness, financial hardship, and loneliness are, nevertheless, well-trodden paths. One man who can guide us along the way is Seneca the Younger, a Roman philosopher and statesman and contemporary of Jesus. Seneca suffered from asthma, and his condition sometimes left him bedridden and gasping for air. As he grew older, he even contemplated suicide because his affliction was so severe. Seneca’s lifelong illness, as well as his background in Stoic philosophy, gave him the insight he needed to find dignity and joy in periods of extended hardship. “There are times,” he once wrote, “when even to live is an act of bravery.”

You don’t have to test positive for COVID-19 to appreciate the consolation offered by Seneca’s wisdom.

More here.

Anti-Parasitic Drug Halts Coronavirus Replication in Lab-Grown Cells within 48 Hours

From Gen Eng News:

An anti-parasitic drug that is available around the world stops SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus from replicating in cells within a couple of days, according to findings from in vitro studies by Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI), working with the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity.

An anti-parasitic drug that is available around the world stops SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus from replicating in cells within a couple of days, according to findings from in vitro studies by Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI), working with the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity.

BDI research lead Kylie Wagstaff, PhD, said the studies showed that the drug, ivermectin, started to become effective against SARS-CoV-2 in lab-grown cells within just a day. “We found that even a single dose could essentially remove all viral RNA by 48 hours and that even at 24 hours there was a really significant reduction in it,” Wagstaff commented. The researchers’ report is available as a pre-proof paper in Antiviral Research, titled, “The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.”

Ivermectin is approved by the FDA for treating a number of parasitic infections, and the drug has an established safety profile, the authors wrote. Studies have suggested that ivermectin may also be effective in vitro against a broad range of viruses, including HIV, Dengue, influenza, and Zika virus. Wagstaff made a previous breakthrough finding on ivermectin in 2012, when, in collaboration with BDI co-author David Jans, PhD, she identified antiviral activity of ivermectin. Jans and his team have been researching the antiviral effects of ivermectin for more than 10 years.

More here.

Bill Gates on where the COVID-19 pandemic will hurt the most

Trump, Scorsese, and the Frankfurt School’s Theory of Racket Society

Martin Jay in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

“THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL Knew Trump was Coming” announced an essay by Alex Ross in The New Yorker on December 5, 2016. Much, in fact, has been made of late of the prescience of the Frankfurt School in anticipating the rise of populist nationalism in general and Donald Trump in particular. By and large, the focus has been on their critiques of the culture industry, the authoritarian personality, the techniques of right-wing agitators, and antisemitism. Another aspect of their legacy has, however, been largely ignored, which supplements their insights into the psychological and cultural sources of the problem, and deepens their analysis of the demagogic techniques of the agitator. I’m referring here to their oft-neglected analysis of what they called a “racket society” to explain the unexpected rise of fascism.

“THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL Knew Trump was Coming” announced an essay by Alex Ross in The New Yorker on December 5, 2016. Much, in fact, has been made of late of the prescience of the Frankfurt School in anticipating the rise of populist nationalism in general and Donald Trump in particular. By and large, the focus has been on their critiques of the culture industry, the authoritarian personality, the techniques of right-wing agitators, and antisemitism. Another aspect of their legacy has, however, been largely ignored, which supplements their insights into the psychological and cultural sources of the problem, and deepens their analysis of the demagogic techniques of the agitator. I’m referring here to their oft-neglected analysis of what they called a “racket society” to explain the unexpected rise of fascism.

Its current relevance can be fully appreciated if we take a detour through Martin Scorsese’s widely acclaimed 2019 film The Irishman, which chronicles the career of mob hit man Frank Sheeran, among whose most notable victims — or so he claimed to his biographer Charles Brandt in I Heard You Paint Houses — was Teamster Union president Jimmy Hoffa. Whether or not the movie convincingly solves the mystery of Hoffa’s disappearance in 1975, it brilliantly succeeds in painting a vivid picture of a violent, amoral world in which power relations are transactional and the threat of betrayal haunts even the most seemingly loyal friendships.

More here.

Brazilian Grooves

Fernanda Melchor’s Many-Voiced Mexican Noir

Ana Cecilia Alvarez at Bookforum:

Melchor’s sentences ensnare the reader within the characters’ delusions, their small, persistent faiths, their regrets, their resentments. Her prose is as ornate as Sebald’s, turning in on itself, forming fractal spirals of meaning. But while Sebald’s sentences have a stately, lecture-hall air to them, Melchor’s sound more like a drunk’s slurred tale. It’s the breathless monologue of good gossip or the bitter outpouring of religious profession, with no paragraph break, no gasp for air. What makes the writing mesmerizing is the almost imperceptible way that Melchor is able to inflect each character’s voice within the novel’s sustained tone of a close, omniscient third-person narration. The effect, subtle yet transfixing, is of a narrator slipping into each character as if slipping into a new skin, without collapsing into any stable “I.”

Melchor’s sentences ensnare the reader within the characters’ delusions, their small, persistent faiths, their regrets, their resentments. Her prose is as ornate as Sebald’s, turning in on itself, forming fractal spirals of meaning. But while Sebald’s sentences have a stately, lecture-hall air to them, Melchor’s sound more like a drunk’s slurred tale. It’s the breathless monologue of good gossip or the bitter outpouring of religious profession, with no paragraph break, no gasp for air. What makes the writing mesmerizing is the almost imperceptible way that Melchor is able to inflect each character’s voice within the novel’s sustained tone of a close, omniscient third-person narration. The effect, subtle yet transfixing, is of a narrator slipping into each character as if slipping into a new skin, without collapsing into any stable “I.”

more here.

The Black Gambling King of Chicago

Michael LaPointe at The Paris Review:

If you could trace the fate of just one dollar that passed through the hands of John “Mushmouth” Johnson, where would it lead? It probably came to his hands off a craps table or from an office of his policy syndicate, and more likely than not, it would go on to be slipped into the pocket of some crooked cop or double-dealing politician. But if Johnson, whom local papers called “the Negro Gambling King of Chicago,” managed to hold on to it, that dollar might end up supporting a hub of black music in the twenties, or the first black-owned bank in Chicago, or a poetic precursor of the Harlem Renaissance. It would grant Johnson, in death, a respectability he was denied in life.

If you could trace the fate of just one dollar that passed through the hands of John “Mushmouth” Johnson, where would it lead? It probably came to his hands off a craps table or from an office of his policy syndicate, and more likely than not, it would go on to be slipped into the pocket of some crooked cop or double-dealing politician. But if Johnson, whom local papers called “the Negro Gambling King of Chicago,” managed to hold on to it, that dollar might end up supporting a hub of black music in the twenties, or the first black-owned bank in Chicago, or a poetic precursor of the Harlem Renaissance. It would grant Johnson, in death, a respectability he was denied in life.

Johnson’s life was characterized by a constant tension between philanthropy and corruption. Born to the nurse of Mary Todd Lincoln in 1857, Johnson moved from his native Saint Louis to Chicago at an early age. Some said his nickname, Mushmouth, referred to how much he cursed.

more here.

100 days that changed the world

Michael Safi in The Guardian:

A turbulent decade had reached its final day. It was New Year’s Eve 2019 and much of the world was preparing to celebrate. The obituaries of the 2010s had dwelt on eruptions and waves that would shape the era ahead: Brexit, the Syrian civil war, refugee crises, social media proliferation, and nationalism roaring back to life. They were written too soon. It was not until these last hours, before the toasts and countdowns had commenced, that the decade’s most consequential development of all broke the surface. At 1.38pm on 31 December, a Chinese government website announced the detection of a “pneumonia of unknown cause” in the area surrounding the South China seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, an industrial city of 11 million people. The outbreak was one of at least a dozen to be confirmed by the World Health Organization that December, including cases of Ebola in west Africa, measles in the Pacific and dengue fever in Afghanistan. Outside China, its discovery was barely noticed. Over the next 100 days, the virus would freeze international travel, extinguish economic activity and confine half of humanity to their homes, infecting more than a million people and counting, including an Iranian vice-president, the actor Idris Elba, and the British prime minister. By the middle of April, more than 75,000 would be dead. But all that was still unimaginable at the end of December, as 11.59pm ticked over to midnight, fireworks exploded and people embraced at parties and in packed streets.

A turbulent decade had reached its final day. It was New Year’s Eve 2019 and much of the world was preparing to celebrate. The obituaries of the 2010s had dwelt on eruptions and waves that would shape the era ahead: Brexit, the Syrian civil war, refugee crises, social media proliferation, and nationalism roaring back to life. They were written too soon. It was not until these last hours, before the toasts and countdowns had commenced, that the decade’s most consequential development of all broke the surface. At 1.38pm on 31 December, a Chinese government website announced the detection of a “pneumonia of unknown cause” in the area surrounding the South China seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, an industrial city of 11 million people. The outbreak was one of at least a dozen to be confirmed by the World Health Organization that December, including cases of Ebola in west Africa, measles in the Pacific and dengue fever in Afghanistan. Outside China, its discovery was barely noticed. Over the next 100 days, the virus would freeze international travel, extinguish economic activity and confine half of humanity to their homes, infecting more than a million people and counting, including an Iranian vice-president, the actor Idris Elba, and the British prime minister. By the middle of April, more than 75,000 would be dead. But all that was still unimaginable at the end of December, as 11.59pm ticked over to midnight, fireworks exploded and people embraced at parties and in packed streets.

Day 1, Wednesday 1 January: Wuhan seafood market shut down

The Wuhan seafood market is ordinarily bustling, but this morning police are weaving tape between its metal frames and hustling owners to shut their blue roller doors. Workers in hazmat suits carefully take samples from surfaces and place them in sealed plastic bags. Concerned messages are circulating on Chinese social media, fuelled by medical documents that have found their way online warning that patients have been presenting at Wuhan hospitals with ominous symptoms.

…Day 99, Wednesday 8 April: Future course of pandemic still unknown

Boris Johnson remains in hospital, having been admitted to intensive care on Monday after his symptoms worsened. In some of Europe’s worst-hit countries, new transmissions and deaths are falling. China has recorded its first day with zero deaths and is cautiously reopening cities. Last Saturday may have been the deadliest day so far, with more than 6,500 fatalities around the world. But with some of the poorest and most populous countries still officially relatively untouched by the virus, it is too early to say for sure. Singapore, which was celebrated for its swift response, has introduced a strict quarantine amid signs of a possible second wave of infections. Vaccines are being fast-tracked but are unlikely to be in mass supply for at least 18 months.

Pakistan is reopening its construction sector. With a quarter of its population in poverty, the country is walking a tightrope between slowing down the virus and “ensuring people don’t die of hunger and our economy doesn’t collapse”, says the prime minister, Imran Khan.

More here.

Can an Old Vaccine Stop the New Coronavirus?

Roni Caryn Rabin in The New York Times:

A vaccine that was developed a hundred years ago to fight the tuberculosis scourge in Europe is now being tested against the coronavirus by scientists eager to find a quick way to protect health care workers, among others. The Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine is still widely used in the developing world, where scientists have found that it does more than prevent TB. The vaccine prevents infant deaths from a variety of causes, and sharply reduces the incidence of respiratory infections. The vaccine seems to “train” the immune system to recognize and respond to a variety of infections, including viruses, bacteria and parasites, experts say. There is little evidence yet that the vaccine will blunt infection with the coronavirus, but a series of clinical trials may answer the question in just months. On Monday, scientists in Melbourne, Australia, started administering the B.C.G. vaccine or a placebo to thousands of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists and other health care workers — the first of several randomized controlled trials intended to test the vaccine’s effectiveness against the coronavirus.

A vaccine that was developed a hundred years ago to fight the tuberculosis scourge in Europe is now being tested against the coronavirus by scientists eager to find a quick way to protect health care workers, among others. The Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine is still widely used in the developing world, where scientists have found that it does more than prevent TB. The vaccine prevents infant deaths from a variety of causes, and sharply reduces the incidence of respiratory infections. The vaccine seems to “train” the immune system to recognize and respond to a variety of infections, including viruses, bacteria and parasites, experts say. There is little evidence yet that the vaccine will blunt infection with the coronavirus, but a series of clinical trials may answer the question in just months. On Monday, scientists in Melbourne, Australia, started administering the B.C.G. vaccine or a placebo to thousands of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists and other health care workers — the first of several randomized controlled trials intended to test the vaccine’s effectiveness against the coronavirus.

“Nobody is saying this is a panacea,” said Nigel Curtis, an infectious diseases researcher at the University of Melbourne and Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, who planned the trial. “What we want to do is reduce the time an infected health care worker is unwell, so they recover and can come back to work faster.” A clinical trial of 1,000 health care workers began 10 days ago in the Netherlands, said Dr. Mihai G. Netea, an infectious disease specialist at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen. Eight hundred health care workers have already signed up. (As in Australia, half of the participants will receive a placebo.) Dr. Denise Faustman, director of immunobiology at Massachusetts General Hospital, is seeking funding to start a clinical trial of the vaccine in health care workers in Boston as well. Preliminary results could be available in as little as four months.

“We have really strong data from clinical trials with humans — not mice — that this vaccine protects you from viral and parasitic infections,” said Dr. Faustman. “I’d like to start today.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

San Francisco

All the way west, where Isadora Duncan was born

and saw her family ruined

in finance, to which her response

was drop out of class, teach dance: I’m reading the latest

conference abstracts, which assure

us that the right distance

answers any statistical question.

Mine is distrust in the premise, life

as an aggregate task,

where the threshold of significance, technically, lapses

to insignificant anything that risked going missing.

Isn’t that what the coast

means, after all: past the chance for time and space?

All? Everything counts

because everything lasts.

Duncan’s children were drowned. Her school was unheated.

Her last words—to love!—were shameful and thus misquoted.

Out here, they build on the faults

because they know nowhere else. The man who promised

me forever, then left, would shudder

in his sleep as if dreaming a past of quakes

or a future: I held on. It doesn’t matter

that no one predicts their own happiness

and everyone is in pain,

that the best use of a mind is to unmake its own inaccurate

faith that what comes next

will be utterly different and utterly the same.

Or the best use of the body, not the mind.

Duncan, running: she “left herself behind.”

by Siobhan Phillips

from The Ecotheo Review, 4/29/15

A Letter to My Students as We Face the Pandemic

George Saunders in The New Yorker:

Jeez, what a hard and depressing and scary time. So much suffering and anxiety everywhere. (I saw this bee happily buzzing around a flower yesterday and felt like, Moron! If you only knew!) But it also occurs to me that this is when the world needs our eyes and ears and minds. This has never happened before here (at least not since 1918). We are (and especially you are) the generation that is going to have to help us make sense of this and recover afterward. What new forms might you invent, to fictionalize an event like this, where all of the drama is happening in private, essentially? Are you keeping records of the e-mails and texts you’re getting, the thoughts you’re having, the way your hearts and minds are reacting to this strange new way of living? It’s all important. Fifty years from now, people the age you are now won’t believe this ever happened (or will do the sort of eye roll we all do when someone tells us something about some crazy thing that happened in 1970.) What will convince that future kid is what you are able to write about this, and what you’re able to write about it will depend on how much sharp attention you are paying now, and what records you keep.

Jeez, what a hard and depressing and scary time. So much suffering and anxiety everywhere. (I saw this bee happily buzzing around a flower yesterday and felt like, Moron! If you only knew!) But it also occurs to me that this is when the world needs our eyes and ears and minds. This has never happened before here (at least not since 1918). We are (and especially you are) the generation that is going to have to help us make sense of this and recover afterward. What new forms might you invent, to fictionalize an event like this, where all of the drama is happening in private, essentially? Are you keeping records of the e-mails and texts you’re getting, the thoughts you’re having, the way your hearts and minds are reacting to this strange new way of living? It’s all important. Fifty years from now, people the age you are now won’t believe this ever happened (or will do the sort of eye roll we all do when someone tells us something about some crazy thing that happened in 1970.) What will convince that future kid is what you are able to write about this, and what you’re able to write about it will depend on how much sharp attention you are paying now, and what records you keep.

Also, I think, with how open you can keep your heart. I’m trying to practice feeling something like, “Ah, so this is happening now,” or “Hmm, so this, too, is part of life on Earth. Did not know that, universe. Thanks so much, stinker.”

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Scott Barry Kaufman on the Psychology of Transcendence

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

If one of the ambitious goals of philosophy is to determine the meaning of life, one of the ambitious goals of psychology is to tell us how to achieve it. An influential work in this direction was Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — a list of human needs, often displayed suggestively in the form of a pyramid, ranging from the most basic (food and shelter) to the most refined. At the top lurks “self-actualization,” the ultimate goal of achieving one’s creative capacities. Psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman has elaborated on this model, both by exploring less-well-known writings of Maslow’s, and also by incorporating more recent empirical psychological studies. He suggests the more dynamical metaphor of a sailboat, where the hull represents basic security needs and the sail more creative and dynamical capabilities. It’s an interesting take on the importance of appreciating that the nature of our lives is one of constant flux.

If one of the ambitious goals of philosophy is to determine the meaning of life, one of the ambitious goals of psychology is to tell us how to achieve it. An influential work in this direction was Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs — a list of human needs, often displayed suggestively in the form of a pyramid, ranging from the most basic (food and shelter) to the most refined. At the top lurks “self-actualization,” the ultimate goal of achieving one’s creative capacities. Psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman has elaborated on this model, both by exploring less-well-known writings of Maslow’s, and also by incorporating more recent empirical psychological studies. He suggests the more dynamical metaphor of a sailboat, where the hull represents basic security needs and the sail more creative and dynamical capabilities. It’s an interesting take on the importance of appreciating that the nature of our lives is one of constant flux.

More here.

Dinner and a Fight

Katherine Scott Nelson’s extraordinary essay, “Dinner and a Fight,” recounts their past experience in the gig economy, working as a waiter and bartender at catering events in the Chicago area. It’s an insecure life of low pay, no insurance (though injuries lurk around every corner), and no future. Compounding these difficulties, Nelson, who is a nonbinary trans person pursuing gender transition, worked in a business where male and female boundaries are carefully marked. Yet throughout this essay Nelson displays a can-do brio, a stubborn slogging bravery, and even humor, which adds poignancy to the march of one grinding day after another. In these sudden, terrifying days of the coronavirus pandemic, the lives of the people you will read about here have become even more precarious, as our country’s shameful economic and healthcare inequality worsens in the crisis. —Philip Graham

Katherine Scott Nelson’s extraordinary essay, “Dinner and a Fight,” recounts their past experience in the gig economy, working as a waiter and bartender at catering events in the Chicago area. It’s an insecure life of low pay, no insurance (though injuries lurk around every corner), and no future. Compounding these difficulties, Nelson, who is a nonbinary trans person pursuing gender transition, worked in a business where male and female boundaries are carefully marked. Yet throughout this essay Nelson displays a can-do brio, a stubborn slogging bravery, and even humor, which adds poignancy to the march of one grinding day after another. In these sudden, terrifying days of the coronavirus pandemic, the lives of the people you will read about here have become even more precarious, as our country’s shameful economic and healthcare inequality worsens in the crisis. —Philip Graham

Katherine Scott Nelson in Ninth Letter:

I am a cater waiter. I go when and where I’m called: hotel lobby parties for fertilizer sales conferences in downtown Chicago, million-dollar weddings in suburban backyards festooned with pink tulle, outside in hundred-degree heat on Western Illinois golf courses, holiday parties at Lake Shore Drive condos where the client sarcastically asks if she’s still allowed to wish us a Merry Christmas, pristine penthouse conference rooms where lawyers discuss international weapons contracts over sea salt caramel truffles and fresh coffee.

In my all-black uniform, I can be as invisible and silent as a ninja. I have a pickpocket’s skill at palming dinner rolls, a homing pigeon’s sense of taco trucks, and an alcoholic’s knowledge of how late everything is open. I can swing ten boiling-hot plates of beef tenderloin over one shoulder without burning the curve of my ear, and carry them from a makeshift outdoor kitchen across wet grass and up half a flight of stairs without spilling half a drop of red wine reduction sauce, and maneuver my way back without dropping so much as a greasy butter knife down the back of a guest’s dress (most of the time).

More here.