Month: April 2020

Generation C Has Nowhere to Turn

Amanda Mull in The Atlantic:

Once people are let out into the world to rejoin their lives, the pandemic will continue to harm them for years to come. “Epidemics are really bad for economies,” says Elena Conis, a historian of medicine and public health at UC Berkeley, laughing slightly at the understatement. “We’re going to see a whole bunch of college graduates and people finishing graduate programs this summer who are going to really struggle to find work.” If you’re willing to risk your life to mop hospital floors or fetch abandoned carts in grocery-store parking lots, a paycheck, however meager, is certainly in your future.

Once people are let out into the world to rejoin their lives, the pandemic will continue to harm them for years to come. “Epidemics are really bad for economies,” says Elena Conis, a historian of medicine and public health at UC Berkeley, laughing slightly at the understatement. “We’re going to see a whole bunch of college graduates and people finishing graduate programs this summer who are going to really struggle to find work.” If you’re willing to risk your life to mop hospital floors or fetch abandoned carts in grocery-store parking lots, a paycheck, however meager, is certainly in your future.

For Americans who either can’t do those jobs or aren’t desperate enough to try them, little relief is coming, relative to what other rich nations are doing for their populations. In Denmark, the government is paying up to 90 percent of employees’ salaries to keep businesses afloat and ensure that people have jobs when the pandemic ends. In the United Kingdom, the government will cover up to 80 percent of workers’ wages. In the United States, onetime relief checks of up to $1,200 per person are coming in the months ahead for people who had certain income and tax statuses in previous years, as well as expanded unemployment insurance for those who have lost work. But that’s only if you can successfully navigate the glutted, byzantine systems required to sign up for unemployment benefits. No one seems to know how the protections for gig workers are supposed to function or how small-business owners should obtain the loans they were promised. In the meantime, rent is still due.

These economic conditions are dangerous for nearly all Americans, but older people are more likely to have stable professional lives and finances to help cushion the blow. People just starting out now, and those who will begin their adult lives in the years following the pandemic, will be asked to walk a financial tightrope with no practice and, for most, no safety net.

More here.

The Better Half: On the Genetic Superiority of Women – bold study of chromosomal advantage

Gaia Vince in The Guardian:

It was noticeable from the initial outbreak in Wuhan that Covid-19 was killing more men than women. By February, data from China, which involved 44,672 confirmed cases of the respiratory disease, revealed the death rate for men was 2.8%, compared to 1.7% among women. For past respiratory epidemics, including Sars, Mers and the 1918 Spanish flu, men were also at significantly greater risk. But why? Much of the reason for the Covid-19 disparity was put down to men’s riskier behaviours – around half of Chinese men are smokers, compared with just 3% of women, for instance. But as the coronavirus has spread globally, it’s proved deadlier to men everywhere that data exists (the UK and US notably – and questionably – do not collect sex-disaggregated data). Italy, for instance, has had a case fatality rate of 10.6% for men, versus 6% for women, whereas the sex disparity for smoking (now a known risk factor) is smaller there than China – 28% of men and 19% of women smoke. In Spain, twice as many men as women have died. Smoking, then, is unlikely to account for all of the sex disparity in Covid-19 deaths.

It was noticeable from the initial outbreak in Wuhan that Covid-19 was killing more men than women. By February, data from China, which involved 44,672 confirmed cases of the respiratory disease, revealed the death rate for men was 2.8%, compared to 1.7% among women. For past respiratory epidemics, including Sars, Mers and the 1918 Spanish flu, men were also at significantly greater risk. But why? Much of the reason for the Covid-19 disparity was put down to men’s riskier behaviours – around half of Chinese men are smokers, compared with just 3% of women, for instance. But as the coronavirus has spread globally, it’s proved deadlier to men everywhere that data exists (the UK and US notably – and questionably – do not collect sex-disaggregated data). Italy, for instance, has had a case fatality rate of 10.6% for men, versus 6% for women, whereas the sex disparity for smoking (now a known risk factor) is smaller there than China – 28% of men and 19% of women smoke. In Spain, twice as many men as women have died. Smoking, then, is unlikely to account for all of the sex disparity in Covid-19 deaths.

Age and co-morbidity (pre-existing health conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease or cancer) are the biggest risk factors, and that describes more older men than women. There may also be a sex difference in how people fight infection, due to immunological or hormonal differences – oestrogen is shown to increase the antiviral response of immune cells. If women are mounting a more effective immune response to Covid-19, it could be because many of the genes that regulate the immune system are encoded on the X chromosome. Everybody gets one X chromosome at conception from their mother. However, sex is determined (for the vast majority) by the chromosome received from their father: females get an additional X, whereas males do not (they receive a Y). According to The Better Half by American physician Sharon Moalem, having this second X chromosome gives women an immunological advantage. Every cell in a woman’s body has twice the number of X chromosomes as a man’s, and so twice the number of genes that can be called upon to regulate her immune response, he says.

More here.

Sunday Poem

From “Clearances”

When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of clean water.

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other’s work would bring us to our senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent toward my head,

Here breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives—

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

by Seamus Heaney

from A Book of Luminous Things

Houghton Mifflin, 1996

The Brilliant Plodder

David Quammen in The New York Review of Books:

Charles Darwin is ever with us. A month seldom passes without new books about the man, his life, his work, and his influence—books by scholars for scholars, by scholars for ordinary readers, and by the many unwashed rest of us nonfiction authors who presume to enter the fray, convinced that there’s one more new way to tell the story of who Darwin was, what he actually said or wrote, why he mattered. This flood of books, accompanied by a constant outpouring of related papers in history journals and other academic outlets, is called the Darwin Industry.

There’s a parallel to this in publishing: the Lincoln Industry, which by one authoritative count had yielded 15,000 books—a towering number—as of 2012, when an actual tower of Lincoln books was constructed in the lobby of the renovated Ford’s Theatre, the site of his assassination, in Washington, D.C. It rose thirty-four feet, measured eight feet around, yet contained less than half the total Lincoln library. You could think of the Darwin library as a similar tower of books three stories high, big around as an oak, festooned with biographies and philosophical treatises and evolutionary textbooks and Creationist tracts and the latest sarcastic volume of The Darwin Awards for suicidal stupidity and books with subtitles such as “Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity.” Janet Browne’s magisterial two-volume life would be included; so would David Dobbs’s Reef Madness, about Darwin’s theory of the formation of coral atolls, and a handful of books on the Scopes trial. Lincoln and Darwin were born on the very same date, February 12, 1809: a good day for the publishing business.

More here.

The lure of fascism

Jonathan Wolff in Aeon:

Jonathan Wolff in Aeon:

Ours is the age of the rule by ‘strong men’: leaders who believe that they have been elected to deliver the will of the people. Woe betide anything that stands in the way, be it the political opposition, the courts, the media or brave individuals. While these demonised guardians of freedom are belittled, brushed aside or destroyed, vulnerable groups, such as refugees, immigrants, minorities and those living in poverty, bear the brunt. What can be done to halt or reverse this process? And what will happen if we simply stand by and watch? Some commentators see parallels with the rise of fascism in the 1930s. Others agree that democracy is under threat but suggest that the threats are new. A fair point, but with its dangers. Yes, we must attend to new threats, but old ones can reoccur too.

Stefan Zweig, the Austrian author of Jewish descent, saw his books burnt in university towns across Germany in 1933. His memoirs paint a picture in which everything was normal until it wasn’t. But it would be wrong to think that we can predict how things will turn out. Who foresaw where we are now? The French philosopher Simone Weil, writing in 1934, probably had it right: ‘We are in a period of transition; but a transition towards what? No one has the slightest idea.’

Liberal democratic institutions, such as those we have now, exist only so long as people believe in them. When that belief evaporates, change can be rapid. Beware leaders riding a wave of crude nationalism. Beware democracy submerging into a vague notion of the will of the people. But why now?

More here.

There Is No Panacea for the Coronavirus Economy

John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

John Cassidy in The New Yorker:

Despite a month of shutdowns and distancing measures, the virus hasn’t stopped spreading, but the rate of new infections has gone down. At a national level, based on figures from the Covid Tracking Project, the number of cases is rising by about 4.7 per cent, which is down from about 7.5 per cent a week ago. Ian Shepherdson, the founder of Pantheon Macroeconomics, has been looking at what’s happening in other countries, too. In the past week or so, Germany, Spain, and Italy have announced limited steps to reopen stores and other businesses. These countries waited until the daily new infection rate had fallen to a bit below the current U.S. level, Shepherdson said. By this time next week, the U.S. rate may well have closed that gap.

In absolute terms, however, the number of new infections is still much higher in the United States, because the over-all number of cases is so large. So far, most governors, Republican and Democrat, have resisted the idea of lifting stay-at-home orders. But the economic cost of the shutdown is rising—in the past four weeks, more than twenty-two million Americans have lost their jobs or been furloughed, figures released on Thursday showed. And in some Democrat-run states, conservative protesters have staged demonstrations against the restrictions, with Trump openly egging them on.

The big question is what will happen if some businesses do start to reopen.

More here.

Simone de Beauvoir: 1975 Interview

Feminism Means a Lot of Things

Jennifer Szalai at the NYT:

Reading “Burn It Down!,” an anthology of feminist manifestos edited by Breanne Fahs, I couldn’t decide whether the book amounted to a celebration or an elegy. In her learned and impassioned introduction, Fahs starts out by enumerating a litany of feminist accomplishments only to pair most of them with their backlash. Federally supported family leave? Typically unpaid. Women’s studies programs? They exist, but they’re dwindling. Abortion access may have expanded worldwide; in the United States, though, it’s in jeopardy. “We have returned again to a period of cultural reckoning,” Fahs writes, pointing to a “reinvigoration of misogyny and racism” that would have been “eerily familiar” to any number of activists whose manifestos appear in this volume.

Reading “Burn It Down!,” an anthology of feminist manifestos edited by Breanne Fahs, I couldn’t decide whether the book amounted to a celebration or an elegy. In her learned and impassioned introduction, Fahs starts out by enumerating a litany of feminist accomplishments only to pair most of them with their backlash. Federally supported family leave? Typically unpaid. Women’s studies programs? They exist, but they’re dwindling. Abortion access may have expanded worldwide; in the United States, though, it’s in jeopardy. “We have returned again to a period of cultural reckoning,” Fahs writes, pointing to a “reinvigoration of misogyny and racism” that would have been “eerily familiar” to any number of activists whose manifestos appear in this volume.

more here.

Returning to Mansfield Park

Janet Todd at the TLS:

more here.

Camus’s Inoculation Against Hate

Laura Marris in The New York Times:

Toward the end of January, I began to notice a strange echo between my work and the news. A mysterious virus had appeared in the city of Wuhan, and though the virus resembled previous diseases, there was something novel about it. But I’m not a doctor, an epidemiologist or a public health expert; I’m a literary translator. Usually my work moves more slowly than the events of the moment, since translation involves lingering over the patterns of a sentence or the connotations of a word. But this time the pace of my work and the pace of the virus were eerily similar. That’s because I’m translating Albert Camus’s novel “The Plague.”

Toward the end of January, I began to notice a strange echo between my work and the news. A mysterious virus had appeared in the city of Wuhan, and though the virus resembled previous diseases, there was something novel about it. But I’m not a doctor, an epidemiologist or a public health expert; I’m a literary translator. Usually my work moves more slowly than the events of the moment, since translation involves lingering over the patterns of a sentence or the connotations of a word. But this time the pace of my work and the pace of the virus were eerily similar. That’s because I’m translating Albert Camus’s novel “The Plague.”

One morning, my task was to revise a scene in which the young doctor Rieux, realizing that plague has broken out in the Algerian city of Oran, tries to persuade his bureaucratic colleagues that they should take the outbreak seriously. He knows that if they don’t, half the city will die. The city’s leader doesn’t want to alarm people. He would prefer to avoid calling this disease what it is. When someone says “plague,” the politician looks at the door, making sure no rumor of this word has escaped down the tidy administrative hallways. The dramatic irony is delicious — like watching characters debate the word “bomb” when there’s one ticking under the table. Dr. Rieux is impatient. “You’re looking at the problem wrong,” he says. “It’s not a question of vocabulary, it’s a question of time.”

As I translated that sentence, I felt a fissure open between the page and the world, like a curtain lifted from a two-way mirror. When I looked at the text, I saw the world behind it — the ambulance sirens of Bergamo, the quarantine of Hubei province, the odd disjunction between spring flowers at the market and hospital ships in the news. It was — and is — very difficult to focus, to navigate between each sentence and its real-time double, to find the fuzzy edges where these reflections meet.

More here.

The pros and cons of screening

Natasha Gilbert in Nature:

Impotence and incontinence are common side effects of treatment for prostate cancer. For men with aggressive forms of the disease, these treatment consequences will outweigh the alternative — prostate cancer is one of the biggest cancer killers in men. But a large proportion of people diagnosed with prostate cancer are treated for slow-growing tumours that would have been unlikely to cause harm if left alone — the potential side effects of treatment overshadow the gains. These people are treated because their cancers are flagged by screening programmes. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are also common outcomes of breast-cancer screening, leading researchers to question whether screening for these cancers is doing more harm than good.

Impotence and incontinence are common side effects of treatment for prostate cancer. For men with aggressive forms of the disease, these treatment consequences will outweigh the alternative — prostate cancer is one of the biggest cancer killers in men. But a large proportion of people diagnosed with prostate cancer are treated for slow-growing tumours that would have been unlikely to cause harm if left alone — the potential side effects of treatment overshadow the gains. These people are treated because their cancers are flagged by screening programmes. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are also common outcomes of breast-cancer screening, leading researchers to question whether screening for these cancers is doing more harm than good.

“Used wisely, screening for breast and prostate cancer can significantly reduce an individual’s risk of dying from those cancers. However, the potential benefits may not necessarily outweigh the expected harms and costs of screening on a population level,” says Sigrid Carlsson, an epidemiologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Screening for cancer is designed to catch disease early, when physicians have the best chance of treating it. But differences in opinion over the benefits of breast- and prostate-cancer screening have led to confusing and contradictory recommendations about which people to screen, when and how often. Screening for other types of cancer such as colorectal and cervical cancer is less controversial because they tend to be slower growing, more homogeneous and more readily detected and removed with fewer serious side effects, say researchers.

Scientists are trying to resolve the issues over breast- and prostate-cancer screening by developing more-accurate screening tools. One persistent theme is the push for an individualized approach — each person’s risk is assessed in a way that allows them to make an informed decision.

More here.

Satrurday Poem

Kumari

Dear Kumari,

I, of course, do not know if Kumari was really your name,

It became a custom in the Gulf to change the name of the servant upon arrival,

The mama says to you, “Your name is Maryam/Fatima/Kumari/Chandra,”

Even before she gives you your cotton apron,

The same apron that the previous Kumari used

Before she ran away

And became free

Crowded in a single room with ten others

Watching their pictures on the walls

Fading under the air conditioners.

Kumari,

They may talk to you in English

And give you your own room,

But they will dress you in a pink uniform,

For the concubine is no longer required to seduce.

Or they may talk to you in Arabic and the language of fingers,

That which depends on hand signs in some days,

Or on slapping your cheeks in others.

You might have to help the son

Discover his sexual desires,

Or even sacrifice

For the father’s bodily failures.

In both cases, do not run to the police station,

From there all fathers and sons come.

Read more »

Proposal for “smart lockdowns” for Pakistan

Feisal H. Naqvi in The News:

How is the state supposed to deal with the economic consequences of a lockdown? What happens if supply chains break down? How are daily wagers supposed to feed themselves in the absence of economic activity? What happens if social order breaks down?

How is the state supposed to deal with the economic consequences of a lockdown? What happens if supply chains break down? How are daily wagers supposed to feed themselves in the absence of economic activity? What happens if social order breaks down?

One very original answer based on “smart lockdowns” has been proposed by my friend, Rashid Langrial. His work builds on the insight that when faced with two terrifying choices, the best option is to try and “de-risk” the situation so that one is not faced with only binary options.

Smart lockdowns are based on graduated restrictions ranging from a complete curfew to relative freedom. More importantly, the restrictions would not be applied nationally, provincially or even across one particular city but only to those specific zones where infection is prevalent.

By Langrial’s estimate, a smart lockdown approach would allow 90 percent of the country to stay relatively open. The economy would not be unfettered. But it would survive.

But how does one implement smart lockdowns?

To begin with, Pakistan’s population of 210 million would be organised into economically independent zones using three principles. First, the boundaries would be clearly demarcated and easily communicable. Second, the boundaries would be demarcated to maintain the existing social fabric of the area. Third, the zones would be economically integrated so that at least 80 percent of a zone’s economic activity would be internal to that zone.

More here.

Our Pandemic Summer: The fight against the coronavirus won’t be over when the U.S. reopens and here’s how the nation must prepare itself

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

As I wrote last month, the only viable endgame is to play whack-a-mole with the coronavirus, suppressing it until a vaccine can be produced. With luck, that will take 18 to 24 months. During that time, new outbreaks will probably arise. Much about that period is unclear, but the dozens of experts whom I have interviewed agree that life as most people knew it cannot fully return. “I think people haven’t understood that this isn’t about the next couple of weeks,” said Michael Osterholm, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota. “This is about the next two years.”

As I wrote last month, the only viable endgame is to play whack-a-mole with the coronavirus, suppressing it until a vaccine can be produced. With luck, that will take 18 to 24 months. During that time, new outbreaks will probably arise. Much about that period is unclear, but the dozens of experts whom I have interviewed agree that life as most people knew it cannot fully return. “I think people haven’t understood that this isn’t about the next couple of weeks,” said Michael Osterholm, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota. “This is about the next two years.”

The pandemic is not a hurricane or a wildfire. It is not comparable to Pearl Harbor or 9/11. Such disasters are confined in time and space. The SARS-CoV-2 virus will linger through the year and across the world. “Everyone wants to know when this will end,” said Devi Sridhar, a public-health expert at the University of Edinburgh. “That’s not the right question. The right question is: How do we continue?”

More here.

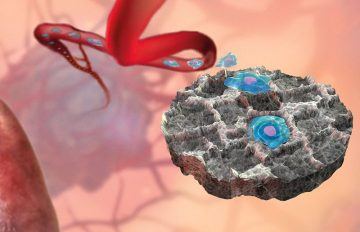

‘Cancer traps’ detect early signs of spread

Elizabeth Svaboda in Nature:

An animal study has shown that implanting a tiny, cell-attracting scaffold below the skin can help physicians to track cancer progression, potentially reducing the need for tissue biopsy. Researchers have observed that before malignant tumours spread from their primary location to other parts of the body, they deploy circulating tumour molecules that suppress the body’s immune response — a strategy that makes it easier for the cancer to infiltrate distant organs. Bioengineer Lonnie Shea at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and his team developed a scaffold that could detect and trap circulating immune and cancer cells during the period before a cancer spreads.

An animal study has shown that implanting a tiny, cell-attracting scaffold below the skin can help physicians to track cancer progression, potentially reducing the need for tissue biopsy. Researchers have observed that before malignant tumours spread from their primary location to other parts of the body, they deploy circulating tumour molecules that suppress the body’s immune response — a strategy that makes it easier for the cancer to infiltrate distant organs. Bioengineer Lonnie Shea at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and his team developed a scaffold that could detect and trap circulating immune and cancer cells during the period before a cancer spreads.

The team’s minuscule trap is made of biodegradable polyester and designed to be implanted under the skin, near vital organs such as the lungs or bones. The polyester in the implant is porous and attracts immune cells such as macrophages, which in turn coax circulating tumour cells to attach on to the scaffold. The team found that differences in the expression levels of ten genes carried by immune cells can indicate a spreading cancer. In tests on mice, the researchers could distinguish between mice without cancer, mice with non-spreading cancers and mice with metastasizing cancers. If this method works similarly in humans, the team says, it might be possible to pick up impending metastases at an earlier stage, and thus allow for more effective treatment. And because taking samples from the scaffold is less invasive than a biopsy, the implant could enable physicians to monitor a person’s condition more frequently. The scaffolds might even slow the spread of some metastases by stopping circulating cancer cells in their tracks.

More here.

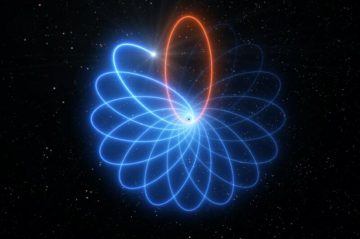

Einstein wins again: Star orbits black hole just like GR predicts

Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

It’s been nearly 30 years in the making, but scientists with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) collaboration in the Atacama Desert in Chile have now measured, for the very first time, the unique orbit of a star orbiting the supermassive black hole believed to lie at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. The path of the star (known as S2) traces a distinctive rosette-shaped pattern (similar to a spirograph), in keeping with one of the central predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The international collaboration described their results in a new paper in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

It’s been nearly 30 years in the making, but scientists with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) collaboration in the Atacama Desert in Chile have now measured, for the very first time, the unique orbit of a star orbiting the supermassive black hole believed to lie at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. The path of the star (known as S2) traces a distinctive rosette-shaped pattern (similar to a spirograph), in keeping with one of the central predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The international collaboration described their results in a new paper in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

“General relativity predicts that bound orbits of one object around another are not closed, as in Newtonian gravity, but precess forwards in the plane of motion,” said Reinhard Genzel, director at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Garching, Germany. “This famous effect—first seen in the orbit of the planet Mercury around the Sun—was the first evidence in favor of general relativity. One hundred years later we have now detected the same effect in the motion of a star orbiting the compact radio source Sagittarius A* (SagA*) at the center of the Milky Way.”

When Einstein developed his general theory of relativity, he proposed three classical tests to confirm its validity.

More here.

Watch this rare, striking footage of a snow leopard calling out in the wild

Does the Pandemic Have a Purpose?

Stephen T. Asma in the New York Times:

Many religious people see something benevolent in nature, or at least see purpose dimly grasped in the interworking of biology. But there’s something even deeper than religious optimism. There is a broader conception of nature — shared by monotheists, polytheists, Indigenous animists, and now politicians and policymakers. It is the mythopoetic view of nature. It is the universal instinct to find (or project) a plot in nature. A mythopoetic paradigm or perspective sees the world primarily as a dramatic story of competing personal intentions, rather than a system of objective, impersonal laws. It’s a prescientific worldview, but it is also alive and well in the contemporary mind.

Many religious people see something benevolent in nature, or at least see purpose dimly grasped in the interworking of biology. But there’s something even deeper than religious optimism. There is a broader conception of nature — shared by monotheists, polytheists, Indigenous animists, and now politicians and policymakers. It is the mythopoetic view of nature. It is the universal instinct to find (or project) a plot in nature. A mythopoetic paradigm or perspective sees the world primarily as a dramatic story of competing personal intentions, rather than a system of objective, impersonal laws. It’s a prescientific worldview, but it is also alive and well in the contemporary mind.

More here.

Fake Plastic Trees