by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Bill Murray

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Close cropped with a natty little mustache, Godfrey is kempt, forties, paunch-softened, with an easy smile. A veteran guide, he has been here before. Says it will take five hours to do the 250 kilometers to the crater and so it does.

No package tour jets preceded us when we flew into Kilimanjaro International Airport aboard a small plane from Nairobi, so the airport bank wasn’t open. Consequently, we have no Tanzanian Shillings.

Oxen pull plows across the fields. Buses are occasional and private cars are rarer than cows. At the time of this visit (several years ago), the road is primarily for foot traffic, human and animal. No matter how far from a village, people are everywhere walking on the roads, always. They only move to the verge, reluctantly, when a Land Rover thunders by.

The few vehicles you do pass are either chock full of ride-sharing local folks, or they’re hauling two or three white Europeans on safari, or maybe they’re jeeps that read something like, “Africa Wildlife Research Project, funded by Belgian government.”

What do you know, way out here Godfrey knows where to buy a few beers. Two hot Tuskers from Kenya, two hot Safari beers from Tanzania, a roadside bodega, no power, no refrigeration, just a handful of dusty beers on a shelf for four for five dollars at an anonymous shack, friendly enough, opaque to a stranger. Godfrey’s got this round. Read more »

I’ve been thinking about it a lot recently, how we regulate our minds. It can be simply things, like listening to some music, taking a walk, taking a few deep breaths, a time-out, maybe we take in a movie, or have some coffee, wine or liquor? perhaps smoke some weed – it’s legal now in America, at least in some states. Maybe one meditates, perhaps every now and then, perhaps daily; perhaps you go on a retreat for a week, a month, two or three. One can see a shrink, get a prescription or two. Read a good novel? Take an evening class at the local community college. For that matter, isn’t education about training the mind?

It’s what we do, one of the things. Regulating the mind. The list could grow and grow.

But I’ve got something more specific in mind. I’m interested in those various moments either when: one’s mind impresses itself on you as a stranger, as something perhaps a little perhaps a lot foreign, or you take a leap to see whether or not your mind will catch you. Welcome to your mind. And welcome to the world.

Herewith I offer a collection of experiences. I’m embarrassed to say that they’re my own. I don’t regard them as particularly special. They’re just the experiences I know about. They span my life from about age four to perhaps thirty.

We all have such liminal experiences, each in our own way.

Fiddle-De-Dee

That’s the earliest more or less distinct memory I’ve got, Burl Ives singing that song. I’m told I played the record over and over, on one occasion driving my visiting Uncle Harry to distraction. As I note in the preface to Beethoven’s Anvil, “It is my mind’s tether to history, my umbilical to the world.“

Since that particular experience happened at the house on Cherry Lane, I would have to have been four years old or so at the time. Though, come to think of it, there is an exceedingly vague impression of the house in Ellsworth, where we’d lived before moving to Cherry Lane in Johnstown, Pa. Read more »

by Sarah Firisen

When I moved into a new, larger apartment with my boyfriend a couple of months ago, I decided to buy a Roomba, robot vacuum cleaner. I named her Joanne. I love Joanne, my boyfriend is less of a fan. He finds her hour and a half or so a day moving around the apartment to be intrusive. He doesn’t appreciate me going around beforehand and picking his things off the floor so that she doesn’t get caught in them. When I was at work one day and she got stuck, it was a toss up whether he was going to rescue her or not – he did, but grudgingly. He says to me, “Why does she have to vacuum every day? You don’t vacuum every day”. My response, “Let’s set the bar a little higher than my housekeeping”. And it’s true, Joanne does takes a long time to do what I can do pretty quickly. And she can’t, and doesn’t get to every spot. On the other hand, she can get to spots under cabinets, or beds, that I can’t, or at least don’t get to. Does she clean as well in one session as a professional cleaner would? No. Does she clean better over the course of a week than I do, definitely. Read more »

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. A Prologue can be found here. A table of contents with links to previous chapters can be found here.

by Akim Reinhardt

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

During the mid-19th century, when secretive men’s fraternal societies such as the Masons and Shriners became popular, the Improved Orders of Red Men was one such organization. Members occasionally dressed as make believe Indians and “whooped” it up. Although most people today have not heard of them, some Red Men societies held on until the late 20th century. Indeed, my own Baltimore neighborhood had a Tecumseh chapter building when I moved here in 2003.

By the early 20th century, dressing up as Indians had become a trendy pursuit for boys. The Boy Scouts promoted this appropriation, and it soon spread to countless summer camps across America. This childish cosplay was widespread during the first half of the Cold War, when Hollywood Westerns were at their peak of popularity, both in movie theaters and on TV. Countless backyard games of cowboys and Indians ensued, along with a fresh wave of children dressing up as both. Read more »

Alison Flood in The Guardian:

Sixty years after the French Nobel laureate Albert Camus died in a car crash at the age of 46, a new book is arguing that he was assassinated by KGB spies in retaliation for his anti-Soviet rhetoric.

Sixty years after the French Nobel laureate Albert Camus died in a car crash at the age of 46, a new book is arguing that he was assassinated by KGB spies in retaliation for his anti-Soviet rhetoric.

Italian author Giovanni Catelli first aired his theory in 2011, writing in the newspaper Corriere della Sera that he had discovered remarks in the diary of the celebrated Czech poet and translator Jan Zábrana that suggested Camus’s death had not been an accident. Now Catelli has expanded on his research in a book titled The Death of Camus.

Camus died on 4 January 1960 when his publisher Michel Gallimard lost control of his car and it crashed into a tree. The author was killed instantly, with Gallimard dying a few days later. Three years earlier, the author of L’Étranger (The Outsider) and La Peste (The Plague) had won the Nobel prize for “illuminat[ing] the problems of the human conscience in our times”.

More here.

Peter Lynch in The Irish Times:

Although abstract in character, mathematics has concrete origins: the greatest advances have been inspired by the natural world. Recently, a new result in linear algebra was discovered by three physicists trying to understand the behaviour of neutrinos.

Although abstract in character, mathematics has concrete origins: the greatest advances have been inspired by the natural world. Recently, a new result in linear algebra was discovered by three physicists trying to understand the behaviour of neutrinos.

Neutrinos are subatomic particles that interact only weakly with matter, so that they pass easily through a wall, the Earth or a star. The American poet John Updike described them beautifully in his poem Cosmic Gall: Neutrinos, they are very small. / They have no charge and have no mass/ And do not interact at all./ The earth is just a silly ball/ To them, through which they simply pass, / Like dustmaids down a drafty hall/ Or photons through a sheet of glass.

Neutrinos are produced in vast numbers within the sun, and trillions pass harmlessly through our bodies every second. Almost nothing can stop them. Dune (the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment) aims to unlock the mysteries of neutrinos. This international experiment will use particle accelerators to send an intense beam of high-energy neutrinos from Fermilab in Illinois 800 miles through the earth to massive detectors a mile below ground in South Dakota. The experiment may lead to life-saving applications in medicine and could change our understanding of the universe.

More here.

Sam Klug in Public Books:

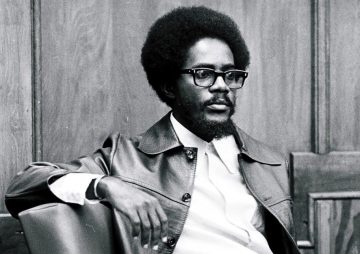

On October 15, 1968, the government of Jamaica banned a 26-year-old history professor from reentering the island nation. Walter Rodney, a lecturer at the University of the West Indies, was returning from the Black Writers’ Congress in Montreal. While abroad, he had spoken out against the Jamaican government’s economic policies, police brutality against black Jamaicans, and exclusion of US Black Power leaders.

On October 15, 1968, the government of Jamaica banned a 26-year-old history professor from reentering the island nation. Walter Rodney, a lecturer at the University of the West Indies, was returning from the Black Writers’ Congress in Montreal. While abroad, he had spoken out against the Jamaican government’s economic policies, police brutality against black Jamaicans, and exclusion of US Black Power leaders.

What was dangerous about Rodney was not only his challenge to the Jamaican government but also that he represented, both within Jamaica and around the world, the possibility of a different kind of world economic order. Today, the Third World suffers because it is excluded from the rules and circuits of a global economy that has borne fruit for the First—or so we are told by leading commentators and scholars of international economics, development, and trade. Rodney recognized that the problem was never that countries like Jamaica were excluded from the global economy. It was that they were included, but on extraordinarily unequal terms.

Looking back at the economic visions that inspired millions in the global South during and after decolonization can help us reassess the language we use to understand global inequality in our own day. These visions are discussed in two new works: historian Sara Lorenzini’s Global Development: A Cold War History and political theorist Adom Getachew’s Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination.

More here.

Justin Tapp in McSweeney’s:

Southwestern Eggrolls – $9.95

Southwestern Eggrolls – $9.95In a tortilla made by the boy’s abuela he watched her, with her armfat and canvas apron, cast frijoles negros upon flecks of cilantro like ash fallen silently on a bed of rice, tiny bones chalkwhite against an avocado ranchero sauce creamy in the light of the coals like the obsidian-flecked desert where God has forsaken all life. Outside a pale starving gallena quickens a lizard to its last writhing gasps. Evening creeps in, a single lobo cries out across the mesa as the sun dips bloodred below the thin black spine of the mountain where death will come again many times in the dusty clockless hours before twilight.

More here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yK6iAxe0oEc

Johanna Thomas-Corr in The Guardian:

Ian McEwan once wrote: “When women stop reading, the novel will be dead.” Back in 2005, he and his son culled the library of his London house and took stacks of books to a local park to give away. He said every woman he approached asked for three, whereas every man “frowned in suspicion, or distaste” and usually said something like: “‘Nah, nah. Not for me. Thanks, mate, but no.’” The history of fiction has always been a history of women readers. From the 18th century, the novel itself was aimed at a new class of leisured women, who didn’t receive formal education in science or politics. The male writers and critics who wrote and appraised the first novels legitimised the form, but Taylor says they “were quickly overtaken by women writers of sensation and romance fiction. Women took to it as a way of learning about other lives, fantasising about their own relationships and narratives that allowed them to challenge their own subordinate position to men.”

Ian McEwan once wrote: “When women stop reading, the novel will be dead.” Back in 2005, he and his son culled the library of his London house and took stacks of books to a local park to give away. He said every woman he approached asked for three, whereas every man “frowned in suspicion, or distaste” and usually said something like: “‘Nah, nah. Not for me. Thanks, mate, but no.’” The history of fiction has always been a history of women readers. From the 18th century, the novel itself was aimed at a new class of leisured women, who didn’t receive formal education in science or politics. The male writers and critics who wrote and appraised the first novels legitimised the form, but Taylor says they “were quickly overtaken by women writers of sensation and romance fiction. Women took to it as a way of learning about other lives, fantasising about their own relationships and narratives that allowed them to challenge their own subordinate position to men.”

Though there have been histories of women’s reading, Taylor’s spirited, engaging study is the first that tries to capture how fiction matters to contemporary women of different ages, classes and ethnic groups. She says that when she tells men the title of her book, they get defensive. “They say, ‘But I read fiction too!’ I say, ‘I’m sure that’s true, but far fewer men do.’ When I scratch beneath the surface to find out why they have read a certain novel, they never give me an emotional answer. It’s always: ‘Well, it’s because I’m very interested in stories about the first world war or the Victorian period.’ Or they say they did history at university and want to follow up certain ideas. Or that they quite like to read Martin Amis because his characters are funny.”

More here.

Monash University in Phys.Org:

Associate Professor Roger Pocock, from the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI), and colleagues from the University of Cambridge led by Professor David Rubinsztein, found that microRNAs are important in controlling protein aggregates, proteins that have amassed due to a malfunction in the process of ‘folding’ that determines their shape. Their findings were published in eLife today. MicroRNAs, short strands of genetic material, are tiny but powerful molecules that regulate many different genes simultaneously. The scientists sought to identify particular microRNAs that are important for regulating protein aggregates and homed in on miR-1, which is found in low levels in patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease. “The sequence of miR-1 is 100 per cent conserved; it’s the same sequence in the Caenorhabditis elegans worm as in humans even though they are separated by 600 million years of evolution,” Associate Professor Pocock said. “We deleted miR-1 in the worm and looked at the effect in a preclinical model of Huntington’s and found that when you don’t have this microRNA there’s more aggregation,” he said. “This suggested miR-1 was important to remove Huntington’s aggregates.”

Associate Professor Roger Pocock, from the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI), and colleagues from the University of Cambridge led by Professor David Rubinsztein, found that microRNAs are important in controlling protein aggregates, proteins that have amassed due to a malfunction in the process of ‘folding’ that determines their shape. Their findings were published in eLife today. MicroRNAs, short strands of genetic material, are tiny but powerful molecules that regulate many different genes simultaneously. The scientists sought to identify particular microRNAs that are important for regulating protein aggregates and homed in on miR-1, which is found in low levels in patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease. “The sequence of miR-1 is 100 per cent conserved; it’s the same sequence in the Caenorhabditis elegans worm as in humans even though they are separated by 600 million years of evolution,” Associate Professor Pocock said. “We deleted miR-1 in the worm and looked at the effect in a preclinical model of Huntington’s and found that when you don’t have this microRNA there’s more aggregation,” he said. “This suggested miR-1 was important to remove Huntington’s aggregates.”

The researchers then showed that miR-1 helped protect against toxic protein aggregates by controlling the expression of the TBC-7 protein in worms. This protein regulates the process of autophagy, the body’s way of removing and recycling damaged cells and is crucial for clearing toxic proteins from cells. “When you don’t have miR-1, autophagy doesn’t work correctly and you have aggregation of these Huntington’s proteins in worms,” Associate Professor Pocock said. Professor Rubinsztein then conducted research which showed that the same microRNA regulates a related pathway to control autophagy in human cells. “Expressing more miR-1 removes Huntington’s aggregates in human cells,” Associate Professor Pocock said. “It’s a novel pathway that can control these aggregation-prone proteins. As a potential means of alleviating neurodegenerative disease, it’s up there,” he said.

More here.

Steven Shapin in the LA Review of Books:

Steven Shapin in the LA Review of Books:

OF COURSE, there’s a Crisis of Truth and, of course, we live in a “Post-Truth” society. Evidence of that Crisis is everywhere, extensively reported in the non-Fake-News media, read by Right-Thinking people. The White House floats the idea of “alternative facts” and the President’s personal attorney explains that “truth isn’t truth.” Trump denies human-caused climate change. Anti-vaxxers proliferate like viruses. These are Big and Important instances of Truth Denial — a lot follows from denying the Truth of expert claims about climate change and vaccine safety. But rather less dangerous Truth-Denying is also epidemic. Astrology and homeopathy flourish in modern Western societies, almost a majority of the American adult public doesn’t believe in evolution, and a third of young Americans think that the Earth may be flat. Meanwhile, Truth-Defenders point an accusatory finger at the perpetrators, with Trump, Heidegger, Latour, Derrida, and Quentin Tarantino improbably sharing a sinful relativist bed.

I’ve mentioned some examples that take a crisis of scientific credibility as an index of the Truth Crisis. Though I’ll stick with science for most of this piece, it’s worth noting that the credibility of many sorts of expert knowledge is also in play — that of the press, medicine, economics and finance, various layers of government, and so on. It was, in fact, Michael Gove, a Conservative British MP, once Minister in charge of the universities, who announced just before the 2016 referendum supporting Brexit that “the people in this country have had enough of experts,” and, while he later tried to walk back that claim, the response to his outburst in Brexit Britain abundantly establishes that he hit a nerve.

More here.

Patrick Blanchfield in Bookforum:

Patrick Blanchfield in Bookforum:

The first test call using America’s 911 emergency system was placed on February 16, 1968. To fanfare in the press, a state legislator sitting in the City Hall of the small Alabama town of Haleyville dialed in to the local police station. His call was answered by a group of august notables—a US representative, a telephone-company executive, and president of the Alabama Public Service Commission Theophilus Eugene Connor. Better remembered today by his nickname, “Bull” Connor was an outspoken white supremacist who believed desegregation was a communist plot; just five years earlier, as commissioner of public safety in Birmingham, he had notoriously unleashed riot police, fire hoses, and attack dogs on nonviolent civil rights protesters.

That such a man should have been on the receiving end of America’s first 911 call is fitting. As Stuart Schrader reveals in his new book, Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing, the United States’ 911 system was modeled on an earlier program pioneered by American-funded police forces fighting a Marxist insurgency in Caracas.

More here.

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

Two of the “freest economies” in the world are on fire. According to indexes of “economic freedom” published annually separately by two conservative thinktanks – the Heritage Foundation and the Fraser Institute – Hong Kong has been number one in the rankings for more than 20 years. Chile is ranked first in Latin America by both indexes, which also place it above Germany and Sweden in the global league table.

Violent protest in Hong Kong has entered its eighth month. The target is Beijing, but the lack of universal suffrage that is catalysing popular anger has long been part of Hong Kong’s economic model. In Chile, where student-led protests against a rise in subway fares turned into a nationwide anti-government movement, the death toll is at least 18.

The rage may be better explained by other rankings: Chile places in the top 25 for economic freedom – and also for income inequality. If Hong Kong were a country, it would be in the world’s top 10 most unequal. Observers often use the word neoliberalism to describe the policies behind this inequality. The term can seem vague, but the ideas behind the economic freedom index help to bring it into focus.

All rankings hold visions of utopia within them. The ideal world described by these indexes is one where property rights and security of contract are the highest values, inflation is the chief enemy of liberty, capital flight is a human right and democratic elections may work actively against the maintenance of economic freedom.

More here.

Mistress Snow in The Chronicle Review:

Mistress Snow in The Chronicle Review:

Something seemed off when I signed into Interfolio one late September morning, during the break between two classes I was teaching. I scanned the dossier a few times, wondering if it could be a glitch, and then it hit me: My mentor had withdrawn her letter of recommendation. In fact, she had withdrawn all of her letters, from 2016 to now. The revelation rang in my ears, like crystal shattering on the floor.

My mentor — let’s call her Anne — was the sole reason I finished my dissertation. While she wasn’t my adviser or even in my primary field, she was my cheerleader and confidante. We had become quite close. She said she felt in loco parentis; I called her my “dissertation mom.” But things fell apart when, desperate to quell her fears after a summer teaching gig fell through, I outed myself to her as a sex worker.

“You will lose all credibility,” she told me in a long, difficult email. As it turned out, in Anne’s eyes, I already had.

The power dynamics that structure mentorship in academia are nebulous at best. In my own department, the only formalized mentor-mentee relationship was the somewhat-arbitrary pairing of graduate students at varying stages of their degrees. Mentorship between students and faculty members was, by contrast, an entirely informal, ad hoc alliance. Boundaries within these relationships are similarly opaque. Mentors can resemble friends, collaborators, parents, and even, occasionally, lovers. But these relationships are never fully severed from the institutional power a mentor has over their mentee — an imbalance that mentors prefer to overlook, even if mentees never really can. Your mentee may be your friend. Your mentor is not.

More here.