Ryu Spaeth in The New Republic:

There is a certain kind of liberally inclined writer who sees Donald Trump’s America as a nation in crisis. At every turn, in every tweet, she is confronted by the signs of an ongoing catastrophe, from which it may be too late to escape. An ugly, vicious intolerance spread on social media; the collapse of norms once considered sacred; a crass narrow-mindedness surreally celebrated by some of this country’s most powerful institutions—these are all elements in the gathering storm of a new, distinctly American fascism. The twist is that this crisis has its source, she contends, not in the person of Trump, but in his frothing-mouthed opposition: the left.

There is a certain kind of liberally inclined writer who sees Donald Trump’s America as a nation in crisis. At every turn, in every tweet, she is confronted by the signs of an ongoing catastrophe, from which it may be too late to escape. An ugly, vicious intolerance spread on social media; the collapse of norms once considered sacred; a crass narrow-mindedness surreally celebrated by some of this country’s most powerful institutions—these are all elements in the gathering storm of a new, distinctly American fascism. The twist is that this crisis has its source, she contends, not in the person of Trump, but in his frothing-mouthed opposition: the left.

That, roughly speaking, is the thesis of a group of writers who, since Trump’s election in 2016, have chastised the left for its supposedly histrionic excesses. Their enemies extend well beyond the hashtag resistance, and their fire is aimed, like a Catherine wheel, in all directions, hitting social justice warriors, elite universities, millennials, #MeToo, pussy hat–wearing women, and columnists at Teen Vogue. Everyone from Ta-Nehisi Coates down to random Facebook commenters is taken to task, which makes for a sprawling, hard-to-define target. These writers might call their bugbear “woke culture”: a kind of vigilance against misogyny, racism, and other forms of inequality expressed in art, entertainment, and everyday life.

More here.

It’s the year of John Ruskin. 2019 is the bicentennial of his birth and there continues to be events to mark it. Perhaps the celebrations will prove to be a turning point for him. For though during his lifetime, and for a generation or so afterwards, Ruskin was hugely influential, his achievements have now been neglected for decades. His collected works run to 39 volumes; he wrote around 250

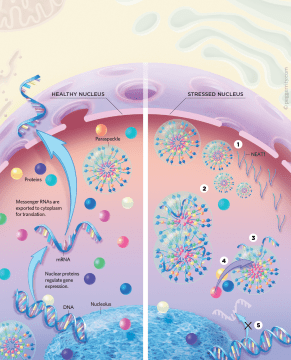

It’s the year of John Ruskin. 2019 is the bicentennial of his birth and there continues to be events to mark it. Perhaps the celebrations will prove to be a turning point for him. For though during his lifetime, and for a generation or so afterwards, Ruskin was hugely influential, his achievements have now been neglected for decades. His collected works run to 39 volumes; he wrote around 250  I have a clear memory of presenting my initial results about a “failed” protein at a lab meeting with my postdoctoral advisor

I have a clear memory of presenting my initial results about a “failed” protein at a lab meeting with my postdoctoral advisor