Jessica Weisberg in The New Yorker:

Commercial surrogacy, the practice of paying a woman to carry and birth a child whom she will not parent, is largely unregulated in America. It’s illegal, with rare exceptions, in three states: New York, Louisiana, and Michigan. But, most states have no surrogacy laws at all. Though the technology was invented in 1986, the concept still seems, for many, a bit sci-fi, and support for it does not follow obvious political fault lines. It is typically championed by the gay-rights community, who see it as the only reproductive technology that allows gay men to have biological children, and condemned by some feminists, who see it as yet another business that exploits the female body. In June, when the New York State Assembly considered a bill that would legalize paid surrogacy, Gloria Steinem vigorously opposed it. “Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others,” Steinem wrote in a statement.

Commercial surrogacy, the practice of paying a woman to carry and birth a child whom she will not parent, is largely unregulated in America. It’s illegal, with rare exceptions, in three states: New York, Louisiana, and Michigan. But, most states have no surrogacy laws at all. Though the technology was invented in 1986, the concept still seems, for many, a bit sci-fi, and support for it does not follow obvious political fault lines. It is typically championed by the gay-rights community, who see it as the only reproductive technology that allows gay men to have biological children, and condemned by some feminists, who see it as yet another business that exploits the female body. In June, when the New York State Assembly considered a bill that would legalize paid surrogacy, Gloria Steinem vigorously opposed it. “Under this bill, women in economic need become commercialized vessels for rent, and the fetuses they carry become the property of others,” Steinem wrote in a statement.

In a new book, “Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against the Family,” the author Sophie Lewis makes a forceful argument for legalization. Lewis takes little interest in the parents. It’s the surrogates who concern her. Regulation, she says, is the only way for them to avoid exploitation. Lewis frequently, if reluctantly, compares surrogacy to sex work, another industry that persists despite being illegal. Banning these jobs is pointless, Lewis says, aside from giving privileged feminists something to do, and making the work more dangerous. “Surrogacy bans uproot, isolate, and criminalize gestational workers, driving them underground and often into foreign lands, where they risk prosecution,” she writes. “As with sex work, the question of being for or against surrogacy is largely irrelevant. The question is, why is it assumed that one should be more against surrogacy than other risky jobs.”

Lewis does not offer straightforward policy suggestions. Her approach to the material is theoretical, devious, a mix of manifesto and memoir. Early in the book, she struggles to understand why anyone would want to get pregnant in the first place, and later she questions whether continuing the human race is a good idea. But she is solemn and unsparing in her assessment of the status quo. A portion of the book studies the Akanksha Fertility Clinic, in India, a surrogacy center that, according to Lewis, severely underpays and mistreats its workers. (Nayana Patel, who runs the clinic, has argued that Akanksha pays surrogates more than they would make at other jobs.) All of the Akanksha surrogates are required to have children of their own already, ostensibly because they know how difficult it is to raise a child and are therefore less likely to want to keep the ones they’re carrying.

More here.

Science seems under assault. Attacks come from many directions, ranging from the political realm to groups and individuals masquerading as scientific entities. There is even a real risk that scientific fact will eventually be reduced to just another opinion, even when those facts describe natural phenomena—the very purpose for which science was developed. Hastening this erosion are hyperbolic claims of “truth” that science is often perceived to make and that practicing researchers may themselves project, whether intentionally or not. I’m a researcher, and I get it. It seems difficult to explain the persistent success of scientific theories at describing nature, not to mention the constant march of technological advancement, without assigning at least some special epistemic status to those theories. I explore this challenge in my book,

Science seems under assault. Attacks come from many directions, ranging from the political realm to groups and individuals masquerading as scientific entities. There is even a real risk that scientific fact will eventually be reduced to just another opinion, even when those facts describe natural phenomena—the very purpose for which science was developed. Hastening this erosion are hyperbolic claims of “truth” that science is often perceived to make and that practicing researchers may themselves project, whether intentionally or not. I’m a researcher, and I get it. It seems difficult to explain the persistent success of scientific theories at describing nature, not to mention the constant march of technological advancement, without assigning at least some special epistemic status to those theories. I explore this challenge in my book,  I read with some interest Alex Byrne’s recent paper,

I read with some interest Alex Byrne’s recent paper,  It’s too easy to take laws of nature for granted. Sure, gravity is pulling us toward Earth today; but how do we know it won’t be pushing us away tomorrow? We extrapolate from past experience to future expectation, but what allows us to do that? “Humeans” (after David Hume, not a misspelling of “human”) think that what exists is just what actually happens in the universe, and the laws are simply convenient summaries of what happens. “Anti-Humeans” think that the laws have a reality of their own, bringing what happens next into existence. The debate has implications for the notion of possible worlds, and thus for counterfactuals and causation — would Y have happened if X hadn’t happened first? Ned Hall and I have a deep conversation that started out being about causation, but we quickly realized we had to get a bunch of interesting ideas on the table first. What we talk about helps clarify how we should think about our reality and others.

It’s too easy to take laws of nature for granted. Sure, gravity is pulling us toward Earth today; but how do we know it won’t be pushing us away tomorrow? We extrapolate from past experience to future expectation, but what allows us to do that? “Humeans” (after David Hume, not a misspelling of “human”) think that what exists is just what actually happens in the universe, and the laws are simply convenient summaries of what happens. “Anti-Humeans” think that the laws have a reality of their own, bringing what happens next into existence. The debate has implications for the notion of possible worlds, and thus for counterfactuals and causation — would Y have happened if X hadn’t happened first? Ned Hall and I have a deep conversation that started out being about causation, but we quickly realized we had to get a bunch of interesting ideas on the table first. What we talk about helps clarify how we should think about our reality and others. I have been triggered into writing this short essay by three events. One is reading Mukul Kesavan’s

I have been triggered into writing this short essay by three events. One is reading Mukul Kesavan’s  The film’s subject is, yes, this France of a century ago, cleaved in two: one half enraged anti-Semites that I have always believed paved the way for the deadliest of European fascism; and another half for whom the affair, still known today in France as “l’Affaire,” shook, unsettled, or sometimes destroyed anti-Semitic prejudices.

The film’s subject is, yes, this France of a century ago, cleaved in two: one half enraged anti-Semites that I have always believed paved the way for the deadliest of European fascism; and another half for whom the affair, still known today in France as “l’Affaire,” shook, unsettled, or sometimes destroyed anti-Semitic prejudices. WHAT MAKES SUICIDE FUNNY?

WHAT MAKES SUICIDE FUNNY? Is it just a writer’s insecurity? As though worried that he, or we, might forget what he’s up against, J M Coetzee regularly produces books that measure themselves alongside canonical predecessors: Life & Times of Michael K wears its debt to Kafka in its title, just as Foe beckons to Robinson Crusoe. The Master of Petersburg is a fantasia that bends Dostoevsky into The Brothers Karamazov. If it isn’t insecurity, it might be hubris, in which case Coetzee’s Jesus trilogy is likely to do little more than strengthen the arguments of his detractors – which monument can I stand next to now, Ma? The sense of a writer finding material worth riffing on never quite goes away, but there is more to it than that: in their needling, selfish, dry-as-dust way, these three books are works of cumulative power and never less than consistent interest.

Is it just a writer’s insecurity? As though worried that he, or we, might forget what he’s up against, J M Coetzee regularly produces books that measure themselves alongside canonical predecessors: Life & Times of Michael K wears its debt to Kafka in its title, just as Foe beckons to Robinson Crusoe. The Master of Petersburg is a fantasia that bends Dostoevsky into The Brothers Karamazov. If it isn’t insecurity, it might be hubris, in which case Coetzee’s Jesus trilogy is likely to do little more than strengthen the arguments of his detractors – which monument can I stand next to now, Ma? The sense of a writer finding material worth riffing on never quite goes away, but there is more to it than that: in their needling, selfish, dry-as-dust way, these three books are works of cumulative power and never less than consistent interest. N

N It’s an idea that has been influential for more than 200 years: around the middle of the first millennium

It’s an idea that has been influential for more than 200 years: around the middle of the first millennium  People sometimes express confusion about what public philosophy is. We see the point as straightforward: it’s a matter of location. Public philosophy consists of all those efforts that aren’t centered on university life. Public philosophers write op-eds for newspapers, work on disability issues and penal reform, serve on expert committees for government agencies, teach in prisons and schools, and help community groups balance considerations of justice with economic development. But while the possibilities for public philosophy are infinite, the distinction is clear: are your attentions directed toward other philosophers? That’s academic philosophy. Are your efforts aimed at the wider world? That’s public philosophy.

People sometimes express confusion about what public philosophy is. We see the point as straightforward: it’s a matter of location. Public philosophy consists of all those efforts that aren’t centered on university life. Public philosophers write op-eds for newspapers, work on disability issues and penal reform, serve on expert committees for government agencies, teach in prisons and schools, and help community groups balance considerations of justice with economic development. But while the possibilities for public philosophy are infinite, the distinction is clear: are your attentions directed toward other philosophers? That’s academic philosophy. Are your efforts aimed at the wider world? That’s public philosophy.

1.

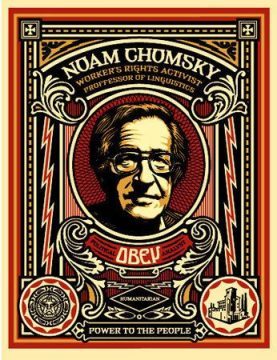

1. A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world.

A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world. Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

If you have read reports about Mr. Barr’s remarks, you probably already know they have been criticized for their ferocious partisanship. There is unquestionably a considerable amount of energy devoted to critiquing those who get in President Trump’s way (Congress, the federal courts, Progressives, and private citizens who exercise their right of free speech). But M

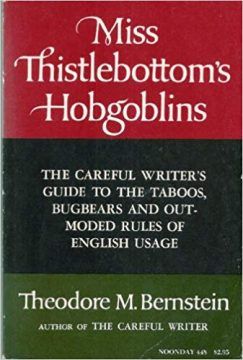

If you have read reports about Mr. Barr’s remarks, you probably already know they have been criticized for their ferocious partisanship. There is unquestionably a considerable amount of energy devoted to critiquing those who get in President Trump’s way (Congress, the federal courts, Progressives, and private citizens who exercise their right of free speech). But M Theodore M. Bernstein – Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins: The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage (1971)

Theodore M. Bernstein – Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins: The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage (1971)