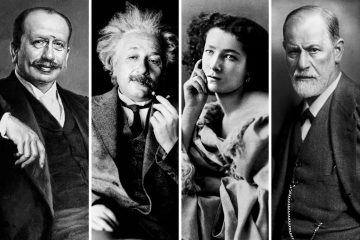

Clemence Boulouque in The New York Times:

Reciting Jewish achievements and Judaism’s contribution to civilization in order to fight anti-Semitic propaganda is a well-established genre that flourished in 19th-century Europe. After reaching the United States in the first part of the 20th century, it arguably culminated in the 1960s with the writings of popular authors like Max Dimont. Norman Lebrecht’s “Genius & Anxiety” belongs to that genre: Both the subtitle of his book and the preface testify to Lebrecht’s commitment to demonstrating “how Jews changed the world” as a response to the current moment, which, he laments, is yet again beset by anti-Semitism.

Reciting Jewish achievements and Judaism’s contribution to civilization in order to fight anti-Semitic propaganda is a well-established genre that flourished in 19th-century Europe. After reaching the United States in the first part of the 20th century, it arguably culminated in the 1960s with the writings of popular authors like Max Dimont. Norman Lebrecht’s “Genius & Anxiety” belongs to that genre: Both the subtitle of his book and the preface testify to Lebrecht’s commitment to demonstrating “how Jews changed the world” as a response to the current moment, which, he laments, is yet again beset by anti-Semitism.

Spanning a century, between 1847 (the death of Felix Mendelssohn) and 1947 (the United Nations’ vote in favor of the creation of the State of Israel), the book features dozens of remarkable scientists, artists and politicians of Jewish descent. Lebrecht’s wide net captures the usual suspects — Marx, Freud, Kafka, Einstein — but also many lesser-known, and equally fascinating, individuals, like Karl Landsteiner, the father of blood types; Albert Ballin, the shipping industry magnate who changed trans-Atlantic journeys and migration patterns; and Eliza Davis, an acquaintance of Dickens who harassed him until he amended “Oliver Twist,” doing away with negative Jewish references in the book’s later editions. Some of Lebrecht’s transitions from one vignette to the next flow particularly well: His account of the revival of ancient Hebrew under the auspices of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, meant to foster a Jewish national consciousness, is aptly followed and contrasted by the depiction of the near-simultaneous creation of Esperanto by the Polish idealist Eliezer Ludwig Zamenhof, who strove to create a universal idiom that would encourage greater understanding among peoples.

More here.

A cave-wall depiction of a pig and buffalo hunt is the world’s oldest recorded story, claim archaeologists who discovered the work on the Indonesian island Sulawesi. The scientists say the scene is more than 44,000 years old.

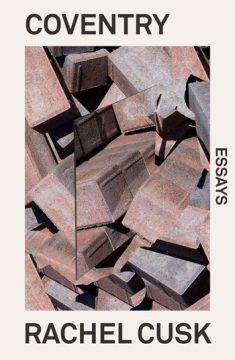

A cave-wall depiction of a pig and buffalo hunt is the world’s oldest recorded story, claim archaeologists who discovered the work on the Indonesian island Sulawesi. The scientists say the scene is more than 44,000 years old. Cusk is best known in the US for her Outline trilogy, a series of slim, challenging novels that follow Faye, a cryptic, intelligent narrator whose life and perspective seem to mirror Cusk’s own. Coventry gathers essays written before, during, and after the period in which Cusk was at work on the trilogy. Almost all have appeared elsewhere, but collecting them gives readers a chance to draw a link between Cusk the memoirist (there are essays on marriage and divorce) and Cusk the novelist (there are short pieces on writers like Edith Wharton, D. H. Lawrence, and Kazuo Ishiguro, as well as longer meditations on literary value).

Cusk is best known in the US for her Outline trilogy, a series of slim, challenging novels that follow Faye, a cryptic, intelligent narrator whose life and perspective seem to mirror Cusk’s own. Coventry gathers essays written before, during, and after the period in which Cusk was at work on the trilogy. Almost all have appeared elsewhere, but collecting them gives readers a chance to draw a link between Cusk the memoirist (there are essays on marriage and divorce) and Cusk the novelist (there are short pieces on writers like Edith Wharton, D. H. Lawrence, and Kazuo Ishiguro, as well as longer meditations on literary value). In 2009, discouraged by the failed climate talks in Copenhagen, Chris told me he believed it might already be too late to stop catastrophic climate change. “The old world,” he said, “is gone.” It was a torch-passing moment. Chris was paralyzed by a conviction in his own failure. He had become complacent, he felt, and addicted to television: the sort of person he used to despise. But I was just beginning my own journey into environmental despair. I was full of guilt and anxiety and anger and fear about a future filled with loss and death. I began to draw my own elliptical lines through the ethics of the climate crisis. I turned off the heat in my house, even during the bitter Utah winters. I was late everywhere, determined to take a bus to another bus to a train. I obsessed over plastic bags and Styrofoam plates, and insisted on bringing my own plate to a local sandwich shop. I carried my garbage around for a week and roped my friends into doing so, too, each of us hauling a stinking reminder of our consumption from class to class, clearing rooms as we went. I joined a direct action climate justice group; I planned blockades of city streets and got arrested. I joined with Utah Valley farmers to organize against urban sprawl.

In 2009, discouraged by the failed climate talks in Copenhagen, Chris told me he believed it might already be too late to stop catastrophic climate change. “The old world,” he said, “is gone.” It was a torch-passing moment. Chris was paralyzed by a conviction in his own failure. He had become complacent, he felt, and addicted to television: the sort of person he used to despise. But I was just beginning my own journey into environmental despair. I was full of guilt and anxiety and anger and fear about a future filled with loss and death. I began to draw my own elliptical lines through the ethics of the climate crisis. I turned off the heat in my house, even during the bitter Utah winters. I was late everywhere, determined to take a bus to another bus to a train. I obsessed over plastic bags and Styrofoam plates, and insisted on bringing my own plate to a local sandwich shop. I carried my garbage around for a week and roped my friends into doing so, too, each of us hauling a stinking reminder of our consumption from class to class, clearing rooms as we went. I joined a direct action climate justice group; I planned blockades of city streets and got arrested. I joined with Utah Valley farmers to organize against urban sprawl.

It is often claimed that the United States differs from Europe in that it lacks a socialist tradition. The title question of Werner Sombart’s 1906 book Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? was answered nearly a century later by Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Wolfe Marks’ It Didn’t Happen Here: Why

It is often claimed that the United States differs from Europe in that it lacks a socialist tradition. The title question of Werner Sombart’s 1906 book Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? was answered nearly a century later by Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Wolfe Marks’ It Didn’t Happen Here: Why  In the summer of

In the summer of Anyone who doubts that genes can specify identity might well have arrived from another planet and failed to notice that the humans come in two fundamental variants: male and female. Cultural critics, queer theorists, fashion photographers, and Lady Gaga have reminded us— accurately—that these categories are not as fundamental as they might seem, and that unsettling ambiguities frequently lurk in their borderlands. But it is hard to dispute three essential facts: that males and females are anatomically and physiologically different; that these anatomical and physiological differences are specified by genes; and that these differences, interposed against cultural and social constructions of the self, have a potent influence on specifying our identities as individuals. That genes have anything to do with the determination of sex, gender, and gender identity is a relatively new idea in our history. The distinction between the three words is relevant to this discussion. By sex, I mean the anatomic and physiological aspects of male versus female bodies. By gender, I am referring to a more complex idea: the psychic, social, and cultural roles that an individual assumes. By gender identity, I mean an individual’s sense of self (as female versus male, as neither, or as something in between).

Anyone who doubts that genes can specify identity might well have arrived from another planet and failed to notice that the humans come in two fundamental variants: male and female. Cultural critics, queer theorists, fashion photographers, and Lady Gaga have reminded us— accurately—that these categories are not as fundamental as they might seem, and that unsettling ambiguities frequently lurk in their borderlands. But it is hard to dispute three essential facts: that males and females are anatomically and physiologically different; that these anatomical and physiological differences are specified by genes; and that these differences, interposed against cultural and social constructions of the self, have a potent influence on specifying our identities as individuals. That genes have anything to do with the determination of sex, gender, and gender identity is a relatively new idea in our history. The distinction between the three words is relevant to this discussion. By sex, I mean the anatomic and physiological aspects of male versus female bodies. By gender, I am referring to a more complex idea: the psychic, social, and cultural roles that an individual assumes. By gender identity, I mean an individual’s sense of self (as female versus male, as neither, or as something in between).

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964) is today best remembered as one of the founders of population genetics, which married Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russell Wallace’s ideas of natural selection with Mendelian genetics using the language of statistics. His other scientific contributions spanned the fields of physiology, biochemistry, and medical genetics – contributions that the evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith once said would “satisfy half a dozen ordinary mortals”.

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (1892-1964) is today best remembered as one of the founders of population genetics, which married Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russell Wallace’s ideas of natural selection with Mendelian genetics using the language of statistics. His other scientific contributions spanned the fields of physiology, biochemistry, and medical genetics – contributions that the evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith once said would “satisfy half a dozen ordinary mortals”. IN LATE 2005

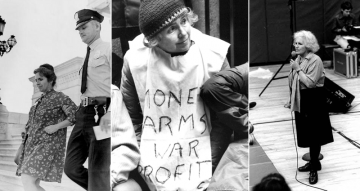

IN LATE 2005 Paley was an artist of the highest order, but she was also an activist, a pacifist, a mother, and a citizen. She saw her several callings as connected, and ideally as indistinct from each other, but when circumstance forced her to choose between protesting the war and making art, or standing up for free speech and making art, or building community and making art, she tended to back-burner the art-making. This may be one reason why her output was relatively slender and why it has been relatively undervalued. I don’t mean to suggest she’s neglected, exactly, only taken for granted at times. Well, whose mother hasn’t been?

Paley was an artist of the highest order, but she was also an activist, a pacifist, a mother, and a citizen. She saw her several callings as connected, and ideally as indistinct from each other, but when circumstance forced her to choose between protesting the war and making art, or standing up for free speech and making art, or building community and making art, she tended to back-burner the art-making. This may be one reason why her output was relatively slender and why it has been relatively undervalued. I don’t mean to suggest she’s neglected, exactly, only taken for granted at times. Well, whose mother hasn’t been?

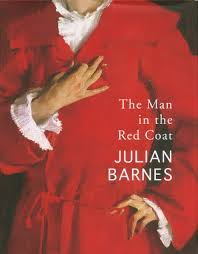

If the book has a raison d’être beyond a mild anti-Brexit subtext, it is Barnes’s repeated plea not to patronise the past – to recognise trailblazers such as Pozzi without chiding his contemporaries for failing to be more like “us” (“We know more and better, don’t we?”). So even if the book hardly qualifies as a work of history, it still delivers a message that all historians should heed.

If the book has a raison d’être beyond a mild anti-Brexit subtext, it is Barnes’s repeated plea not to patronise the past – to recognise trailblazers such as Pozzi without chiding his contemporaries for failing to be more like “us” (“We know more and better, don’t we?”). So even if the book hardly qualifies as a work of history, it still delivers a message that all historians should heed.