Pankaj Mishra in The Guardian:

Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”.

Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”.

Those such as Orwell, who saw through the fantasy, were usually mortified. He was born in Bihar in India to an opium agent, with a Caribbean slave-owner as an ancestor. While working as a colonial policeman in Burma, he discovered imperialism to be an “evil despotism” and Englishness to be a humiliating act: a pose of masculine authority and racial superiority necessary to keep volatile natives in their place. Others such as Enoch Powell, a lower middle-class native of the West Midlands, were seduced by this posture of stiff-upper-lipped preeminence. Powell became a classicist at Cambridge, taught himself fox-hunting, and wrote highly wrought Georgian verse; he exulted, as a brigadier, in the hierarchies of empire in India. Then, like Curzon, Milner, Cromer and other purveyors of an Englishness made in India and Egypt, he came to develop a certain rather fierce idea of England and its destiny.

Orwell, on the other hand, was an archetype of the unpatriotic leftwinger on his return home – until he found a lodestone of native English genius in the “red wall” of northern England. The spirited English response to Hitler’s vicious assault deepened his conviction of having discovered a new “emotional unity” in England – one that a socialist revolution could turn in favour of its downtrodden people. He persuaded himself that “England, together with the rest of the world, is changing”, and a new middle class blending in with the old working class would bring forth “new blood, new men, new ideas”.

More here.

By the first week of March 1915, food supplies inside the besieged fortress of Przemyśl were almost exhausted. Most of the horses that could be spared had been eaten. Bran, sawdust and bone meal were used to eke out the dwindling stock of flour. Cats were nowhere to be seen – they too had been eaten. A middle-sized dog fetched 20 crowns, if its owner could be persuaded to part with it. Even mice were being traded. The hospital was filled to overflowing with collapsing people. As one of the doctors tending them observed, the most shocking thing about the starving was their indifference to their fate. “They silently and without complaint accept a cold place in the hospital, drink the slop which passes here for tea; the next day, they are moved to the morgue.”

By the first week of March 1915, food supplies inside the besieged fortress of Przemyśl were almost exhausted. Most of the horses that could be spared had been eaten. Bran, sawdust and bone meal were used to eke out the dwindling stock of flour. Cats were nowhere to be seen – they too had been eaten. A middle-sized dog fetched 20 crowns, if its owner could be persuaded to part with it. Even mice were being traded. The hospital was filled to overflowing with collapsing people. As one of the doctors tending them observed, the most shocking thing about the starving was their indifference to their fate. “They silently and without complaint accept a cold place in the hospital, drink the slop which passes here for tea; the next day, they are moved to the morgue.”

Reading The Dry Heart is like listening to a person confess in half-truths. The second time the narrator revisits killing Alberto, she describes how she prepared him a thermos of tea with milk and sugar before pulling his revolver out of his desk. The third time, she reveals that he was packing his bags for a trip; that she suspected he was not traveling alone; and that when she told him she would “rather know the truth, whatever it may be,” he replied by misquoting Dante’s Purgatorio: “She seeketh Truth, which is so dear / As knoweth he who life for her refuses.”

Reading The Dry Heart is like listening to a person confess in half-truths. The second time the narrator revisits killing Alberto, she describes how she prepared him a thermos of tea with milk and sugar before pulling his revolver out of his desk. The third time, she reveals that he was packing his bags for a trip; that she suspected he was not traveling alone; and that when she told him she would “rather know the truth, whatever it may be,” he replied by misquoting Dante’s Purgatorio: “She seeketh Truth, which is so dear / As knoweth he who life for her refuses.” I

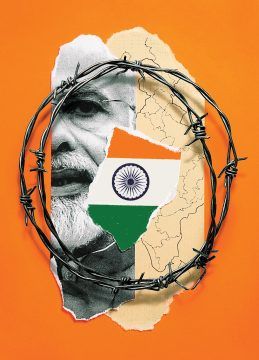

I In August of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India suspended Article 370 of the constitution, the provision that granted some level of autonomy to

In August of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India suspended Article 370 of the constitution, the provision that granted some level of autonomy to  Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”.

Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”. We’re on Flatey, a small island in an archipelago in West Iceland. These islands are clustered in Breiðafjörður, a fjord that Icelanders often talk about in metaphorical terms: “Their freckles were as countless as the islands in Breiðafjörður.” We write this in June, when the sun never forsakes the sky, and half of the island is closed off because it’s nesting season. There are birds everywhere.

We’re on Flatey, a small island in an archipelago in West Iceland. These islands are clustered in Breiðafjörður, a fjord that Icelanders often talk about in metaphorical terms: “Their freckles were as countless as the islands in Breiðafjörður.” We write this in June, when the sun never forsakes the sky, and half of the island is closed off because it’s nesting season. There are birds everywhere. This reliance on models has always been a bête noire for climate change deniers, who have questioned their accuracy as a way of casting doubt on their dire projections. For years, it has been a running battle between scientists and their critics, with the former rallying to defend one dataset and model after another. (The invaluable site Skeptical Science has a

This reliance on models has always been a bête noire for climate change deniers, who have questioned their accuracy as a way of casting doubt on their dire projections. For years, it has been a running battle between scientists and their critics, with the former rallying to defend one dataset and model after another. (The invaluable site Skeptical Science has a  On August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to.

On August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to. Wood points out that contemporary image-based culture — the profusion he can barely sum up by listing “advertising, fashion, celebrities, television, tattoos, toys, comics, pornography, politics, iPhones, and stuff in general” — is impossible for art history to grasp, even though it is to a great extent the content of contemporary art. But his belief that today’s art “is no longer preoccupied with form” is one that would hardly be accepted by most artists or anyone else who is involved in contemporary art on a daily basis.

Wood points out that contemporary image-based culture — the profusion he can barely sum up by listing “advertising, fashion, celebrities, television, tattoos, toys, comics, pornography, politics, iPhones, and stuff in general” — is impossible for art history to grasp, even though it is to a great extent the content of contemporary art. But his belief that today’s art “is no longer preoccupied with form” is one that would hardly be accepted by most artists or anyone else who is involved in contemporary art on a daily basis. Pathetically little has improved for menopausal women since Wilson died in 1981. Our fears, degradations, and inequalities are still blamed on us—and are still well-used by corporate pill-pushers. Pharmaceutical industry watchers estimate that by 2022, the HRT market will be worth an estimated $28.4 billion. (By comparison, the annual revenue of one of the top ten pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, is $40 billion.)

Pathetically little has improved for menopausal women since Wilson died in 1981. Our fears, degradations, and inequalities are still blamed on us—and are still well-used by corporate pill-pushers. Pharmaceutical industry watchers estimate that by 2022, the HRT market will be worth an estimated $28.4 billion. (By comparison, the annual revenue of one of the top ten pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, is $40 billion.) “Mary MacLane is mad,” wrote the New York Herald. “She should be put under medical treatment, and pens and paper kept out of her way until she is restored to reason.” The New York Times urged that she be spanked. Other critics raised the charge of “obscenity.” When the Butte Public Library announced that it would not allow the book on its shelves, the Helena Daily Independent applauded, arguing that if this book “should go in, all the self-respecting books in the library would jump out of the window.”

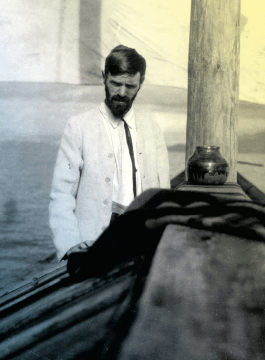

“Mary MacLane is mad,” wrote the New York Herald. “She should be put under medical treatment, and pens and paper kept out of her way until she is restored to reason.” The New York Times urged that she be spanked. Other critics raised the charge of “obscenity.” When the Butte Public Library announced that it would not allow the book on its shelves, the Helena Daily Independent applauded, arguing that if this book “should go in, all the self-respecting books in the library would jump out of the window.” My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew what a coal mine was). As far as I was concerned, Sons and Lovers appeared out of nothing and to nothing it returned. All I knew when I was finished was all I knew before I plucked it, more or less at random, off the shelf: that it was a “classic.”

My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew what a coal mine was). As far as I was concerned, Sons and Lovers appeared out of nothing and to nothing it returned. All I knew when I was finished was all I knew before I plucked it, more or less at random, off the shelf: that it was a “classic.” One hundred and twenty million years ago, when northeastern China was a series of lakes and erupting volcanoes, there lived a tiny mammal just a few inches long. When it died, it was

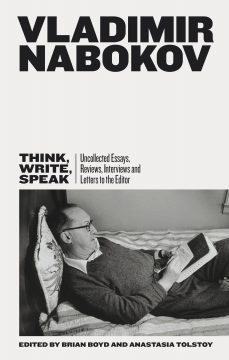

One hundred and twenty million years ago, when northeastern China was a series of lakes and erupting volcanoes, there lived a tiny mammal just a few inches long. When it died, it was  This generous collection of 154 pieces of what Brian Boyd in the introduction calls Nabokov’s ‘public prose’ – mostly uncollected and sometimes also unpublished journalism – is presented chronologically. Where necessary, the pieces have been expertly translated from Russian and French by Boyd and Anastasia Tolstoy, and the notes and index make this book easy to negotiate. The text is marred only by a few idiosyncratic transliterations of Russian words. At first sight, the book may seem to be yet more of those scrapings from the barrel that have been served up over the four decades since Nabokov’s death. However, unlike the embarrassingly jejune fragments of his novels, such as The Original of Laura, that have been published posthumously, this collection includes some of his sharpest prose, as well as his most cursory. It spans Nabokov’s career, from juvenilia to senilia. In Germany, where Nabokov is revered enough for Rowohlt to have published his collected works in twenty-five volumes, a similar anthology of the author’s ‘public prose’ came out fifteen years ago with the title Eigensinnige Ansichten (probably best translated as ‘Stubbornly Held Views’ or ‘Prejudices’). Stubbornness, even perversity, certainly underlies Nabokov’s opinions.

This generous collection of 154 pieces of what Brian Boyd in the introduction calls Nabokov’s ‘public prose’ – mostly uncollected and sometimes also unpublished journalism – is presented chronologically. Where necessary, the pieces have been expertly translated from Russian and French by Boyd and Anastasia Tolstoy, and the notes and index make this book easy to negotiate. The text is marred only by a few idiosyncratic transliterations of Russian words. At first sight, the book may seem to be yet more of those scrapings from the barrel that have been served up over the four decades since Nabokov’s death. However, unlike the embarrassingly jejune fragments of his novels, such as The Original of Laura, that have been published posthumously, this collection includes some of his sharpest prose, as well as his most cursory. It spans Nabokov’s career, from juvenilia to senilia. In Germany, where Nabokov is revered enough for Rowohlt to have published his collected works in twenty-five volumes, a similar anthology of the author’s ‘public prose’ came out fifteen years ago with the title Eigensinnige Ansichten (probably best translated as ‘Stubbornly Held Views’ or ‘Prejudices’). Stubbornness, even perversity, certainly underlies Nabokov’s opinions. Mosquitoes. Hordes of them, buzzing in your ear and biting incessantly, a maddening nuisance without equal. And not to mention the devastating health impacts caused by malaria, Zika virus and other pathogens they spread.

Mosquitoes. Hordes of them, buzzing in your ear and biting incessantly, a maddening nuisance without equal. And not to mention the devastating health impacts caused by malaria, Zika virus and other pathogens they spread. In

In  THE LARGEST CIVIL PROTESTS

THE LARGEST CIVIL PROTESTS