Month: December 2019

A design for death: meeting the bad boy of the euthanasia movement

Mark Smith in 1843 Magazine:

It’s a sunny autumn morning in the Jordaan, Amsterdam’s chocolate-boxiest district. Over tea in a modishly renovated maisonette, a voluble Australian 72 year-0ld wearing round glasses and fashionable denim is regaling me with his new-year plans, which involve “an elegant gas chamber” stationed at a secret location in Switzerland and “a happily dead body”. My host’s name is Philip Nitschke and he’s invented a machine called Sarco. Short for sarcophagus, the slick, spaceship-like pod has a seat for one passenger en-route to the afterlife. It uses nitrogen to enact a pain-free, peaceful death from inert-gas asphyxiation at the touch of a button. With the help of his wife and colleague, the writer and lawyer Dr Fiona Stewart, Nitschke is ushering the death-on-demand movement towards a dramatic new milestone – and their enthusiasm is palpable.

It’s a sunny autumn morning in the Jordaan, Amsterdam’s chocolate-boxiest district. Over tea in a modishly renovated maisonette, a voluble Australian 72 year-0ld wearing round glasses and fashionable denim is regaling me with his new-year plans, which involve “an elegant gas chamber” stationed at a secret location in Switzerland and “a happily dead body”. My host’s name is Philip Nitschke and he’s invented a machine called Sarco. Short for sarcophagus, the slick, spaceship-like pod has a seat for one passenger en-route to the afterlife. It uses nitrogen to enact a pain-free, peaceful death from inert-gas asphyxiation at the touch of a button. With the help of his wife and colleague, the writer and lawyer Dr Fiona Stewart, Nitschke is ushering the death-on-demand movement towards a dramatic new milestone – and their enthusiasm is palpable.

“We’ve got a number of people lined up already, actually,” says Nitschke, whose unique CV (and previous occupation as a registered physician) has earned him the nickname “Dr Death”. The front-runner in the one-way journey to Switzerland is a New Zealander whom Nitschke has known for years. She’s not terminally ill, but is becoming increasingly disabled by macular degeneration – something she finds intolerable after a lifetime of reading for pleasure. “She’s also got an ideological, philosophical supportive commitment to the idea,” explains Nitschke. “She’s coming from a long way because she likes the concept and she sees it as the future.”

Whether that future is utopian or dystopian depends on your perspective. Nitschke has twice been nominated for Australian of the Year for his work with Exit International, the “end-of-life choices information and advocacy organisation” he founded in 1997; activities include the publication of The Peaceful Pill, a continuously updated directory of information on how to end it all. But over the past two decades, members of the medical, psychiatric and even the pro-voluntary euthanasia communities have come to reject his brand of increasingly strident – some say extreme – advocacy for what he terms “rational suicide”: an individual’s inalienable right to die in a manner of their choosing. His one time ally, the former UN medical director Michael Irwin, has branded him “totally irresponsible” for telling people how to obtain drugs that could help them end their own lives. And in August 2019 the grieving daughter of a man who took his life after contact with Exit International denounced Nitschke, saying “the information you put out kills people who are not in a rational state of mind to make that decision.”

More here.

Sunday Poem

Windy Evening

This old world needs propping up

When it gets this cold and windy.

The cleverly painted sets,

Oh, they’re shaking badly!

They’re about to come down.

There’ll be nothing but infinite space.

The silence supreme. Almighty silence.

Egyptian sky. Stars like torches

Of grave robbers entering the crypts of kings.

Even the wind pausing, waiting to see.

Better grab hold of that tree, Lucille.

Its shape crazed, terror-stricken.

I’ll hold on to the barn.

The chickens in it are restless.

Smart chickens, rickety world.

by Charles Simic

from A Wedding in Hell

Harcourt, 1994

Selling Keynesianism

Robert Manduca in Boston Review:

Robert Manduca in Boston Review:

“Let’s bring our editorial microscope into focus on a very significant phenomenon,” the video begins. “The middle-income consumer.”

As a middle-aged white man comes into view, pushing a wheelbarrow full of recent purchases, the voiceover chronicles his recent exploits. “He has fed new demands into the production apparatus of industry, accounting for the housing boom, appliance sales, the rush for prepared foods.” Altogether, we hear, “the zoom in the American market after the war, the unprecedented volume of goods of all kinds, gobbled up by an insatiable tide of buyers, was largely the work of this middle-income man.”

After decades of praise heaped on “job creators,” viewers today may find it disorienting to see the consumer—and a middle-income one at that—cast as the hero of the economy, instead of the investor or the entrepreneur. Yet Fortune, which produced the video in 1956, was hardly an outlier. In the mid-twentieth century, advertising, popular press, and television bombarded Americans with the message that national prosperity depended on their personal spending. As LIFE proclaimed in 1947, “Family Status Must Improve: It Should Buy More For Itself to Better the Living of Others.” Bride likewise told its readers that when they bought new appliances, “you are helping to build greater security for the industries of this country.”

This messaging was not simply an invention of clever marketers; it had behind it the full force of the best-regarded economic theory of the time, the one elaborated in John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).

More here.

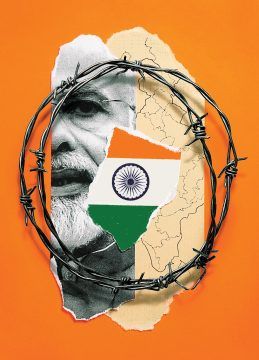

Blood and Soil in Narendra Modi’s India

Dexter Filkins in The New Yorker:

Dexter Filkins in The New Yorker:

In August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to.

Other coverage on Republic TV showed people dancing ecstatically, along with the words “Jubilant Indians celebrate Modi’s Kashmir masterstroke.” A week earlier, Modi’s government had announced that it was suspending Article 370 of the constitution, which grants autonomy to Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state. The provision, written to help preserve the state’s religious and ethnic identity, largely prohibits members of India’s Hindu majority from settling there. Modi, who rose to power trailed by allegations of encouraging anti-Muslim bigotry, said that the decision would help Kashmiris, by spurring development and discouraging a long-standing guerrilla insurgency. To insure a smooth reception, Modi had flooded Kashmir with troops and detained hundreds of prominent Muslims—a move that Republic TV described by saying that “the leaders who would have created trouble” had been placed in “government guesthouses.”

More here.

Afloat with Static

Jenny Turner in the LRB:

Jenny Turner in the LRB:

As a child, Debbie Harry was always searching for ‘the perfect taste’. She couldn’t describe it, but knew she’d know it if she found it. ‘Sometimes, I got a hint of it in peanut butter. Other times … when I drank milk. It was maddening because I was driven to have it.’ She never ate anything, she writes, without wondering if she was at last about to get ‘the flavour of complete satisfaction’.

She grew up and the search was mostly forgotten, though she struggled in secret with bingeing and with worries about getting fat. She’s always been open about the heroin she’s done, over the years, and about how much she enjoyed it: ‘It was so delicious and delightful. For those times when I wanted to blank out parts of my life or when I was dealing with some depression, there was nothing better than heroin. Nothing.’ Now she’s in her seventies, she has ‘a protein and vitamin powder’ that she mixes with coconut water and that tastes ‘satisfyingly familiar’. She blends one up most days. With a careless flip of that flossy halo, the perfect insouciance of her perfect little slotted snarl, she makes the ‘ghostly’ link:

I know that my birth mother kept me for three months. I reason that during this time she breast-fed me and this was the perfect taste. My birth mother kept me and fed me for as long as she could, then she sent me out into the world of choices. The world of flavours. The world. Now, finally, thanks to my maturing, my searching, and my magical shake, I have regained the ability to feel full, to feel hunger, and to enjoy filling up and ending the hunger. True satiation. It seems so simple. Probably as simple as infinity and the universe.

More here.

Walter Benjamin’s Last Work

Samantha Rose Hill in the LA Review of Books:

Samantha Rose Hill in the LA Review of Books:

WHEN HANNAH ARENDT escaped the Gurs internment camp in the middle of June 1940, she did not go to Marseilles to find her husband Heinrich Blücher — she went to Lourdes to find Walter Benjamin. For nearly two weeks they played chess from morning to night, talked, and read whatever papers they could find.

Arendt and Benjamin met in exile in Paris in 1933 through her first husband, Günther Anders, who was a distant cousin of Benjamin’s. They would frequent a café on the rue Soufflot to talk politics and philosophy with Bertolt Brecht and Arnold Zweig. And while Arendt’s marriage to Anders didn’t last, her friendship with Benjamin grew and flourished during the war years.

Arendt hesitated leaving Benjamin in Lourdes. She knew he was in a wobbly state of mind, anxious about the future, talking about suicide. Benjamin feared being interned again, and he had difficulty imagining life in the United States. Arendt wrote to Gershom Scholem that the “war immediately terrified him beyond all measure” and “[h]is horror at America was indescribable.” His strained relationship with Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer at the Institute for Social Research (also known as the Frankfurt School) left him in a state of financial precarity. The tenuous flow of correspondence conducted through networks of friends and letters (when they arrived) complicated matters more, leaving one dependent upon time itself. Benjamin, already an anxious man, stopped going out and “was living in constant panic.”

More here.

The Unending Quest to Explain Consciousness

Michael Robbins at Bookforum:

THE HARD PROBLEM, DAVID CHALMERS CALLS IT: Why are the physical processes of the brain “accompanied by an experienced inner life?” How and why is there something it is like to be you and me, in Thomas Nagel’s formulation? I’ve been reading around in the field of consciousness studies for over two decades—Chalmers, Nagel, Daniel Dennett, John Searle, Jerry Fodor, Ned Block, Frank Jackson, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Alva Noë, Susan Blackmore—and the main thing I’ve learned is that no one has the slightest idea. Not that the field lacks for confident pronouncements to the contrary.

THE HARD PROBLEM, DAVID CHALMERS CALLS IT: Why are the physical processes of the brain “accompanied by an experienced inner life?” How and why is there something it is like to be you and me, in Thomas Nagel’s formulation? I’ve been reading around in the field of consciousness studies for over two decades—Chalmers, Nagel, Daniel Dennett, John Searle, Jerry Fodor, Ned Block, Frank Jackson, Paul and Patricia Churchland, Alva Noë, Susan Blackmore—and the main thing I’ve learned is that no one has the slightest idea. Not that the field lacks for confident pronouncements to the contrary.

Briefly stated, the problem is that the world appears to contain two very different kinds of stuff—mind and body, for which Descartes posited two substances, res cogitans and res extensa. The mind is not physical, not extended in space. The body and everything else are made of physical substance and located in space. Substance dualism is out of fashion these days, but some philosophers (including Chalmers) are property dualists, who believe consciousness is an emergent property, a kind of ghostly accompaniment to physical reality.

more here.

‘The Pulse Glass’ by Gillian Tindall

Anthony Quinn at The Guardian:

Gillian Tindall is a high-minded Autolycus, devoted not merely to snapping up the “unconsidered trifles” of past lives but holding them to the light to glean the stories they might conceal. “Most objects, like all people, disappear in the end,” she writes at the start of The Pulse Glass, an excellent suite of essays on transience and remembrance. And yet not everything crumbles to dust; some bits and pieces defy the odds by surviving, and it is Tindall’s delight – albeit of a measured and low-key sort – to describe their escape from “the quiet darkness of forgetting”.

Gillian Tindall is a high-minded Autolycus, devoted not merely to snapping up the “unconsidered trifles” of past lives but holding them to the light to glean the stories they might conceal. “Most objects, like all people, disappear in the end,” she writes at the start of The Pulse Glass, an excellent suite of essays on transience and remembrance. And yet not everything crumbles to dust; some bits and pieces defy the odds by surviving, and it is Tindall’s delight – albeit of a measured and low-key sort – to describe their escape from “the quiet darkness of forgetting”.

Take, for instance, the scrap of tightly folded paper recently discovered in the crack of a wall at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, possibly to stop up a draught; when examined, it turned out to be a fragment of a musical score by Thomas Tallis, from a service held in St Paul’s in 1544. Or the case of an attic clearance in Westminster Abbey where debris was found strewn across the floor.

more here.

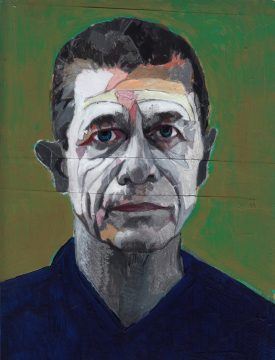

Emmanuel Carrère’s Disconcertingly Personal and Utterly Gripping Prose

Robert Gottlieb at The New York Times:

By breaking with Capote’s model — by “saying yes to the first person,” as Carrère puts it — he had found his way. When his book, “The Adversary,” was published in 2000, not everybody liked it, neither in France, where Carrère was already well known for his novels and screenplays, nor abroad, where he was largely unknown. But the book became a tremendous success, signaling a new approach to the writing of nonfiction: deeply personal, deeply empathetic, disconcertingly self-revelatory. Carrère spared no one, least of all himself. Each of his books became not only a superb account of its subject but a painful report of the author’s struggle to find a way to write it. His reputation grew with every book, until in an excellent profile of him published in The New York Times Magazine in 2017, Wyatt Mason could state with authority: “If Michel Houellebecq is routinely advanced as France’s greatest living writer of fiction, Carrère, whose prose is no less remarkable for its purity and whose vision is no less broad, is widely understood as France’s greatest writer of nonfiction.”

By breaking with Capote’s model — by “saying yes to the first person,” as Carrère puts it — he had found his way. When his book, “The Adversary,” was published in 2000, not everybody liked it, neither in France, where Carrère was already well known for his novels and screenplays, nor abroad, where he was largely unknown. But the book became a tremendous success, signaling a new approach to the writing of nonfiction: deeply personal, deeply empathetic, disconcertingly self-revelatory. Carrère spared no one, least of all himself. Each of his books became not only a superb account of its subject but a painful report of the author’s struggle to find a way to write it. His reputation grew with every book, until in an excellent profile of him published in The New York Times Magazine in 2017, Wyatt Mason could state with authority: “If Michel Houellebecq is routinely advanced as France’s greatest living writer of fiction, Carrère, whose prose is no less remarkable for its purity and whose vision is no less broad, is widely understood as France’s greatest writer of nonfiction.”

That is why the publication of “97,196 Words” is of such consequence. Here, in roughly the order of their original publication, are 20 essays (totaling 97,196 words) that reveal both the depth and the breadth of his achievement.

more here.

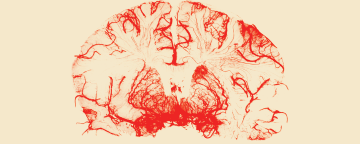

Infographic: Biomarkers in Blood Provide a Window into the Brain

Shawna Williams in The Scientist:

In September of this year, pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai announced that they were halting Phase 3 clinical trials of a drug, elenbecestat, aimed at thwarting amyloid-β buildup in Alzheimer’s disease. Although the drug had seemed so promising that the companies elected to test it in two Phase 3 trials simultaneously, preliminary analyses determined that elenbecestat’s risks outweighed its benefits, and the drug shouldn’t be moved to market. The cancellation “amounts to a further step in the unwinding of Biogen’s expensive, painful, and ultimately fruitless investment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drug development,” analyst Geoffrey Porges told Reuters at the time. Biogen’s misfortune is just the latest in a slew of late-stage Alzheimer’s drug failures. Six months earlier, the company had halted another set of parallel Phase 3 trials due to lack of efficacy of a different drug candidate, aducanumab (though after further data analysis, Biogen announced that it will seek approval for aducanumab after all). And between 2013 and 2018, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Johnson & Johnson all terminated Phase 3 or Phase 2/3 trials due to poor early results. Yet some Alzheimer’s researchers say they think they’ve spotted a silver lining in this cloud of bad news—a hint in the data from these studies about how future work might meet with more success.

In September of this year, pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai announced that they were halting Phase 3 clinical trials of a drug, elenbecestat, aimed at thwarting amyloid-β buildup in Alzheimer’s disease. Although the drug had seemed so promising that the companies elected to test it in two Phase 3 trials simultaneously, preliminary analyses determined that elenbecestat’s risks outweighed its benefits, and the drug shouldn’t be moved to market. The cancellation “amounts to a further step in the unwinding of Biogen’s expensive, painful, and ultimately fruitless investment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drug development,” analyst Geoffrey Porges told Reuters at the time. Biogen’s misfortune is just the latest in a slew of late-stage Alzheimer’s drug failures. Six months earlier, the company had halted another set of parallel Phase 3 trials due to lack of efficacy of a different drug candidate, aducanumab (though after further data analysis, Biogen announced that it will seek approval for aducanumab after all). And between 2013 and 2018, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Johnson & Johnson all terminated Phase 3 or Phase 2/3 trials due to poor early results. Yet some Alzheimer’s researchers say they think they’ve spotted a silver lining in this cloud of bad news—a hint in the data from these studies about how future work might meet with more success.

In some of these trials, Alzheimer’s patients who were at earlier stages of the disease did better than those with more advanced cognitive decline, says Colin Masters, a neuroscientist at Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Australia who was not involved in the trials. This indicates that the key to finding an effective treatment might be to catch subjects before their condition advances too far, he adds. “The idea is very firmly in our minds that you have to go before the onset of cognitive decline, and you may be successful then in actually delaying the onset of cognitive decline by five years, which would be a major advance.” Thanks to the recent development of new detection technologies that yield more-precise and reliable measurements of circulating proteins, RNAs, and other molecules, the field is hoping to do just that.

More here.

Pluck versus luck

David Labaree in Aeon:

Occupants of the American meritocracy are accustomed to telling stirring stories about their lives. The standard one is a comforting tale about grit in the face of adversity – overcoming obstacles, honing skills, working hard – which then inevitably affords entry to the Promised Land. Once you have established yourself in the upper reaches of the occupational pyramid, this story of virtue rewarded rolls easily off the tongue. It makes you feel good (I got what I deserved) and it reassures others (the system really works). But you can also tell a different story, which is more about luck than pluck, and whose driving forces are less your own skill and motivation, and more the happy circumstances you emerged from and the accommodating structure you traversed. As an example, here I’ll tell my own story about my career negotiating the hierarchy in the highly stratified system of higher education in the United States. I ended up in a cushy job as a professor at Stanford University. How did I get there? I tell the story both ways: one about pluck, the other about luck. One has the advantage of making me more comfortable. The other has the advantage of being more true.

Occupants of the American meritocracy are accustomed to telling stirring stories about their lives. The standard one is a comforting tale about grit in the face of adversity – overcoming obstacles, honing skills, working hard – which then inevitably affords entry to the Promised Land. Once you have established yourself in the upper reaches of the occupational pyramid, this story of virtue rewarded rolls easily off the tongue. It makes you feel good (I got what I deserved) and it reassures others (the system really works). But you can also tell a different story, which is more about luck than pluck, and whose driving forces are less your own skill and motivation, and more the happy circumstances you emerged from and the accommodating structure you traversed. As an example, here I’ll tell my own story about my career negotiating the hierarchy in the highly stratified system of higher education in the United States. I ended up in a cushy job as a professor at Stanford University. How did I get there? I tell the story both ways: one about pluck, the other about luck. One has the advantage of making me more comfortable. The other has the advantage of being more true.

…The short story is that I’m in the family business. In the 1920s, my parents grew up as next-door neighbours on a university campus where their fathers were both professors. It was Lincoln University, a historically black institution in southeast Pennsylvania near the Mason-Dixon line. The students were black, the faculty white – most of the latter, like my grandfathers, were clergymen. The students were well-off financially, coming from the black bourgeoisie, whereas the highly educated faculty lived in the genteel poverty of university housing. It was a kind of cultural missionary setting, but more comfortable than the foreign missions. One grandfather had served as a missionary in Iran, where my father was born; that was hardship duty. But here was a place where upper-middle-class whites could do good and do well at the same time.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Hello

She, being the midwife

and your mother’s

longtime friend, said

I see a heart; can you

see it? And on the grey

display of the ultrasound

there you were as you were,

our nugget, in that moment

becoming a shrimp

or a comma punctuating

the whole of my life, separating

its parts—before and after—,

a shrimp in the sea

of your mother, and I couldn’t

help but see the fast

beating of your heart

translated on that screen

and think and say to her,

to the room, to your mother,

to myself It looks like

a twinkling star.

I imagine I’m not

the first to say that either.

Unlike the first moments

of my every day,

the new of seeing you was the first

—deserving of the definite article—

moment I saw a star

at once so small and so

big, so close and getting closer

every day, I pray.

by Sean Hill

from the Academy of American Poets.

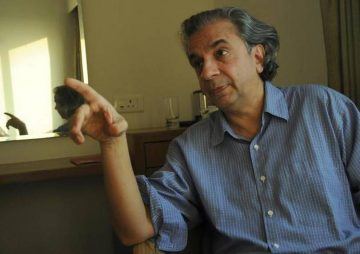

Akeel Bilgrami on Science and Scientism

Akeel Bilgrami in The Immanent Frame:

One need not have phobia about science, while finding what has come to be called “scientism” intellectually distasteful. This is a familiar distinction, oft made.

One need not have phobia about science, while finding what has come to be called “scientism” intellectually distasteful. This is a familiar distinction, oft made.

What exactly is scientism? Very broadly, it is a kind of overreach in the name of science, taking it to a place beyond its proper dominion. This can happen in many ways. One way is in the making of large claims on science’s behalf, claims that are philosophical rather than scientific, yet relying—by a sleight of hand, a fallacious conflation—on the authority of science. I have written critically of one such claim in The Immanent Frame: there is nothing, no property, in nature that cannot be brought under the purview of science as a form of cognitive inquiry. The present contribution spells out some implications of these criticisms.

Those who deny such a claim—say, for instance, by asserting that nature contains value properties, which do not fall within the purview of science—are frequently dismissed as being unscientific. It is this dismissal that amounts to illicit outreach. It can only be unscientific to contradict some proposition in some science. But no science contains the proposition that science has exhaustive coverage of nature and all its properties. So, it cannot be unscientific to deny that it does.

More here.

A will to survive might take AI to the next level

Tom Siegfried in Science News:

“Today’s robots lack feelings,” Man and Damasio write in a new paper (subscription required) in Nature Machine Intelligence. “They are not designed to represent the internal state of their operations in a way that would permit them to experience that state in a mental space.”

“Today’s robots lack feelings,” Man and Damasio write in a new paper (subscription required) in Nature Machine Intelligence. “They are not designed to represent the internal state of their operations in a way that would permit them to experience that state in a mental space.”

So Man and Damasio propose a strategy for imbuing machines (such as robots or humanlike androids) with the “artificial equivalent of feeling.” At its core, this proposal calls for machines designed to observe the biological principle of homeostasis. That’s the idea that life must regulate itself to remain within a narrow range of suitable conditions — like keeping temperature and chemical balances within the limits of viability. An intelligent machine’s awareness of analogous features of its internal state would amount to the robotic version of feelings.

Such feelings would not only motivate self-preserving behavior, Man and Damasio believe, but also inspire artificial intelligence to more closely emulate the real thing.

More here.

In the haze of the California wildfires, a Native American tribe’s independent electricity grid saved the day. Is a new model for energy in America rising from the ashes?

Mitch Anderson in Reasons to be Cheerful:

Early this October about 13,000 people descended onto a poplar casino resort owned by The Blue Lake Rancheria Tribe in Northern California. But the people arriving didn’t come to gamble or play golf — they were there to access the essential ingredient of modern civilization: electricity. As wildfires raged throughout the state, more than a million people on evacuation alert also had to contend with planned blackouts meant to prevent additional fires sparked by downed power lines.

Early this October about 13,000 people descended onto a poplar casino resort owned by The Blue Lake Rancheria Tribe in Northern California. But the people arriving didn’t come to gamble or play golf — they were there to access the essential ingredient of modern civilization: electricity. As wildfires raged throughout the state, more than a million people on evacuation alert also had to contend with planned blackouts meant to prevent additional fires sparked by downed power lines.

The Rancheria had recently installed their own small-scale electrical supply grid using solar panels and Tesla batteries to lower emissions and make their community more resilient to disruptions. So when the lights went out across Humboldt County, the Rancheria’s green “microgrid” was one of the only places with electricity. The tribe opened their doors to a whopping ten percent of the entire county’s population, who were able to charge electric vehicles, access the internet and buy much-needed ice to prevent food from spoiling. People lined up for 30 minutes to buy gasoline from the Blue Lake gas station. Kids warmed up from the chilly fall temperatures and found light to do homework.

More here.

Microdosing LSD in the name of self-improvement

Walter Benjamin’s Last Work

Samantha Rose Hill at the LARB:

When Benjamin was released from the Clos St. Joseph internment camp in Nevers in the spring of 1940, he returned to Paris for a brief period before fleeing to Lourdes around June 14, en route to Marseilles. It was during this time that he wrote what would become his final work, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” or as it is also translated, “On the Concept of History.”

When Benjamin was released from the Clos St. Joseph internment camp in Nevers in the spring of 1940, he returned to Paris for a brief period before fleeing to Lourdes around June 14, en route to Marseilles. It was during this time that he wrote what would become his final work, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” or as it is also translated, “On the Concept of History.”

The “Theses,” a collection of philosophical fragments on historicism and historical materialism, were originally written on the backs of colorful envelopes — green, yellow, orange, blue, cream. The cramped passages in tiny script illustrate the conditions of exile: he is saving space because he is short on paper. As a text, the “Theses” marry Benjamin’s interests in Marxism and theology, reflecting on temporality and the possibility of a weak messianism to interrupt the flow of empty homogeneous, capitalist time. The most famous fragment, which lies at the heart of the work, was inspired by Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus, which Benjamin purchased in 1921, and which inspired a birthday gift from Scholem: a poem titled “Greetings from the Angelus on July 15.”

more here.

Remembering a Time When Composers Mattered More

Sudip Bose at The American Scholar:

A new idea, Rosenberg writes, emerged toward the end of the Second World War, that classical music could be so inspirational to a nation that it might help win a war. Thus was Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony—its first three movements composed in Leningrad as the city was besieged by the Germans—championed in this country as a symbol of freedom and antifascism. The symphony’s artistic merits were less important than its inherent political value, and a national radio audience, hearing the work for the first time on July 19, 1942, was held in a fevered thrall. With the advent of the Cold War and fears growing about the spread of communism, music was increasingly seen to be “interwoven with the democratic aspirations of the American people.” It was, sometimes in not so subtle ways, weaponized. How else to explain the dispatch of symphony orchestras on diplomatic missions abroad? This exporting of American culture to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, where artistic freedoms were brutally suppressed, was both a means of promoting democracy and a master stroke of propaganda. And when the pianist Van Cliburn won first prize at the first Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958, he was feted with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. His triumph went far beyond the realm of art; Cliburn, the tall, handsome Texan who had melted Russian hearts with Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, had scored one for the West.

A new idea, Rosenberg writes, emerged toward the end of the Second World War, that classical music could be so inspirational to a nation that it might help win a war. Thus was Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony—its first three movements composed in Leningrad as the city was besieged by the Germans—championed in this country as a symbol of freedom and antifascism. The symphony’s artistic merits were less important than its inherent political value, and a national radio audience, hearing the work for the first time on July 19, 1942, was held in a fevered thrall. With the advent of the Cold War and fears growing about the spread of communism, music was increasingly seen to be “interwoven with the democratic aspirations of the American people.” It was, sometimes in not so subtle ways, weaponized. How else to explain the dispatch of symphony orchestras on diplomatic missions abroad? This exporting of American culture to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, where artistic freedoms were brutally suppressed, was both a means of promoting democracy and a master stroke of propaganda. And when the pianist Van Cliburn won first prize at the first Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958, he was feted with a ticker-tape parade in New York City. His triumph went far beyond the realm of art; Cliburn, the tall, handsome Texan who had melted Russian hearts with Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, had scored one for the West.

more here.

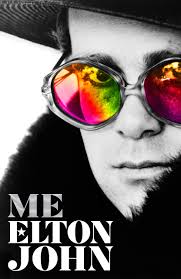

‘Me’ by Elton John

Colm Tóibín at the LRB:

Elton makes no effort to make himself seem good or worthy of the reader’s approval. When he sells all his stuff, he writes: ‘Before you get the wrong idea, I should add that I had absolutely no intention whatsoever of leading a more simple and meaningful life, uncoupled from the yoke of consumerism and unencumbered by material possessions.’ And he makes no secret of the fact that, as he grew older and richer and more famous, he became unbearable. When his house was being emptied of all its goods he moved into a hotel, only to find that he was being kept awake by the wind, so he phoned his office: not to see if he could change rooms, but to demand that something be done about the wind itself. ‘I absolutely was crazy and deluded enough to ring the international manager of Rocket [his company] and ask him to do something about the wind outside my room.’

Elton makes no effort to make himself seem good or worthy of the reader’s approval. When he sells all his stuff, he writes: ‘Before you get the wrong idea, I should add that I had absolutely no intention whatsoever of leading a more simple and meaningful life, uncoupled from the yoke of consumerism and unencumbered by material possessions.’ And he makes no secret of the fact that, as he grew older and richer and more famous, he became unbearable. When his house was being emptied of all its goods he moved into a hotel, only to find that he was being kept awake by the wind, so he phoned his office: not to see if he could change rooms, but to demand that something be done about the wind itself. ‘I absolutely was crazy and deluded enough to ring the international manager of Rocket [his company] and ask him to do something about the wind outside my room.’

But Elton also has a big heart, as his work for Aids charities makes clear.

more here.