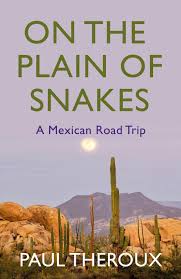

Sara Wheeler at Literary Review:

What does Theroux do on his trip? In Nogales he has his teeth whitened, in San Diego de la Unión he attends a first communion, in San Miguel de Allende he drops in on a wedding and in Monte Albán he inspects pyramids built at a time when ‘Britain was a land of quarrelsome Iron Age tribes painting their bellies blue and huddled in hill forts’. Sometimes he abandons his car, which has Massachusetts plates, in a secure car park and goes on bus journeys. Mexican highways are well maintained, he notes, but the off-ramp ‘always leads to the dusty antique past – to the man plowing a stony field with a burro, to the woman with a bundle on her head, to the boy herding goats, to the ranchitos, the carne asada stands, the five-hundred-year-old churches, and a tienda, selling beer and snacks, with a skinny cat asleep on the tamales’.

What does Theroux do on his trip? In Nogales he has his teeth whitened, in San Diego de la Unión he attends a first communion, in San Miguel de Allende he drops in on a wedding and in Monte Albán he inspects pyramids built at a time when ‘Britain was a land of quarrelsome Iron Age tribes painting their bellies blue and huddled in hill forts’. Sometimes he abandons his car, which has Massachusetts plates, in a secure car park and goes on bus journeys. Mexican highways are well maintained, he notes, but the off-ramp ‘always leads to the dusty antique past – to the man plowing a stony field with a burro, to the woman with a bundle on her head, to the boy herding goats, to the ranchitos, the carne asada stands, the five-hundred-year-old churches, and a tienda, selling beer and snacks, with a skinny cat asleep on the tamales’.

Theroux quotes widely from published sources in both Spanish and English, interviews officials and, as always, talks to ‘ordinary’ people, including some who barely speak Spanish (the Mexican government recognises 68 languages and 350 dialects).

more here.

Harold Bloom, the prodigious literary critic who championed and defended the Western canon in an outpouring of influential books that appeared not only on college syllabuses but also — unusual for an academic — on best-seller lists, died on Monday at a hospital in New Haven. He was 89. His death was confirmed by his wife, Jeanne Bloom, who said he taught his last class at Yale University on Thursday. Professor Bloom was frequently called the most notorious literary critic in America. From a vaunted perch at Yale, he flew in the face of almost every trend in the literary criticism of his day. Chiefly he argued for the literary superiority of the Western giants like Shakespeare, Chaucer and Kafka — all of them white and male, his own critics pointed out — over writers favored by what he called “the School of Resentment,” by which he meant multiculturalists, feminists, Marxists, neoconservatives and others whom he saw as betraying literature’s essential purpose. “He is, by any reckoning, one of the most stimulating literary presences of the last half-century — and the most protean,”

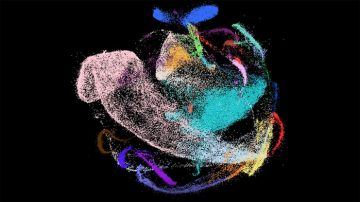

Harold Bloom, the prodigious literary critic who championed and defended the Western canon in an outpouring of influential books that appeared not only on college syllabuses but also — unusual for an academic — on best-seller lists, died on Monday at a hospital in New Haven. He was 89. His death was confirmed by his wife, Jeanne Bloom, who said he taught his last class at Yale University on Thursday. Professor Bloom was frequently called the most notorious literary critic in America. From a vaunted perch at Yale, he flew in the face of almost every trend in the literary criticism of his day. Chiefly he argued for the literary superiority of the Western giants like Shakespeare, Chaucer and Kafka — all of them white and male, his own critics pointed out — over writers favored by what he called “the School of Resentment,” by which he meant multiculturalists, feminists, Marxists, neoconservatives and others whom he saw as betraying literature’s essential purpose. “He is, by any reckoning, one of the most stimulating literary presences of the last half-century — and the most protean,”  The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) latest foray into turning emerging technologies into useful data sets is focusing on how the body’s trillions of cells interconnect and interact. The

The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) latest foray into turning emerging technologies into useful data sets is focusing on how the body’s trillions of cells interconnect and interact. The

I saw Joker last week. I think it’s an excellent film. But the two friends I was with, whose tastes often overlap with my own, really hated it, and we spent the ensuing 90 minutes examining and debating the film. Critics are likewise fiercely divided. Towards the end of our conversation, one friend admitted that, love it or hate it, the film evokes strong reactions; it’s difficult to ignore.

I saw Joker last week. I think it’s an excellent film. But the two friends I was with, whose tastes often overlap with my own, really hated it, and we spent the ensuing 90 minutes examining and debating the film. Critics are likewise fiercely divided. Towards the end of our conversation, one friend admitted that, love it or hate it, the film evokes strong reactions; it’s difficult to ignore.

The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic. —Philip Roth, The Plot Against America

The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic. —Philip Roth, The Plot Against America “What is hidden is for us Westerners more ‘true’ than what is visible,” Roland Barthes proposed, in Camera Lucida, his phenomenology of the photograph, almost forty years ago. In the decades since, the internet, nanotechnology, and viral marketing have challenged his privileging of the unseen over the seen by developing a culture of total exposure, heralding the death of interiority and celebrating the cult of instant celebrity. The icon of this movement, the selfie, is now produced and displayed, in endless daily iterations, in a ritual staging of eyewitness testimony to the festival of self-fashioning.

“What is hidden is for us Westerners more ‘true’ than what is visible,” Roland Barthes proposed, in Camera Lucida, his phenomenology of the photograph, almost forty years ago. In the decades since, the internet, nanotechnology, and viral marketing have challenged his privileging of the unseen over the seen by developing a culture of total exposure, heralding the death of interiority and celebrating the cult of instant celebrity. The icon of this movement, the selfie, is now produced and displayed, in endless daily iterations, in a ritual staging of eyewitness testimony to the festival of self-fashioning. Late morning heat rises in waves over tall grass. It’s an hour and a half drive, sand flies buzzing, to Luwi bush camp, a seasonal camp with just four huts of thatch and grass on a still lagoon, far out into Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park, about 300 miles north of Lusaka.

Late morning heat rises in waves over tall grass. It’s an hour and a half drive, sand flies buzzing, to Luwi bush camp, a seasonal camp with just four huts of thatch and grass on a still lagoon, far out into Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park, about 300 miles north of Lusaka.

This morning I rode an Uber to JFK from my apartment in Queens. I do this regularly and normally don’t worry too much about it, but this morning, there was just something about the driver that concerned me, though I couldn’t put my finger on what. But every time his, very loud, GPS gave him a direction, in a language I couldn’t pin down, I just had this sense that he truly had no idea where he was going. And in case you’re not familiar with NYC, if you drive a car for a living, you’ve probably driven from the city to JFK more than a few times and do know where you’re going. Anyway, we arrived at JFK, I reminded him I wanted terminal 2 and I thought, “I guess my worries were for nothing”. And almost as soon as I thought that, he missed the sign for terminal 2. I mean, I guess it can happen, but it’s never happened to me before in all my many years of flying out of that airport. The signs don’t exactly creep up on you. I tell him he’s missed it; we start on a loop back around the airport and I say, “the green sign’s for terminal 2”, then he misses it again. And it turns out, the reason he kept missing it was because his GPS was telling him something contrary. I pointed out to him that I hadn’t put terminal 2 in Uber, so how would its GPS know that? The third time around the airport, I rather lost my temper and told him to stop listening to his phone and to listen to me. And third time lucky, we reached terminal 2.

This morning I rode an Uber to JFK from my apartment in Queens. I do this regularly and normally don’t worry too much about it, but this morning, there was just something about the driver that concerned me, though I couldn’t put my finger on what. But every time his, very loud, GPS gave him a direction, in a language I couldn’t pin down, I just had this sense that he truly had no idea where he was going. And in case you’re not familiar with NYC, if you drive a car for a living, you’ve probably driven from the city to JFK more than a few times and do know where you’re going. Anyway, we arrived at JFK, I reminded him I wanted terminal 2 and I thought, “I guess my worries were for nothing”. And almost as soon as I thought that, he missed the sign for terminal 2. I mean, I guess it can happen, but it’s never happened to me before in all my many years of flying out of that airport. The signs don’t exactly creep up on you. I tell him he’s missed it; we start on a loop back around the airport and I say, “the green sign’s for terminal 2”, then he misses it again. And it turns out, the reason he kept missing it was because his GPS was telling him something contrary. I pointed out to him that I hadn’t put terminal 2 in Uber, so how would its GPS know that? The third time around the airport, I rather lost my temper and told him to stop listening to his phone and to listen to me. And third time lucky, we reached terminal 2.