Ronald W. Dworkin in The American Interest:

In 2017, scientists at Carnegie Mellon University shocked the gaming world when they programmed a computer to beat experts in a poker game called no-limit hold ’em. People assumed a poker player’s intuition and creative thinking would give him or her the competitive edge. Yet by playing 24 trillion hands of poker every second for two months, the computer “taught” itself an unbeatable strategy.

In 2017, scientists at Carnegie Mellon University shocked the gaming world when they programmed a computer to beat experts in a poker game called no-limit hold ’em. People assumed a poker player’s intuition and creative thinking would give him or her the competitive edge. Yet by playing 24 trillion hands of poker every second for two months, the computer “taught” itself an unbeatable strategy.

Many people fear such events. It’s not just the potential job losses. If artificial intelligence (AI) can do everything better than a human being can, then human endeavor is pointless and human beings are valueless.

Computers long ago surpassed humans in certain skills—for example, in the ability to calculate and catalog. Yet they have traditionally been unable to reproduce people’s creative, imaginative, emotional, and intuitive skills. It is why personalized service workers such as coaches and physicians enjoy some of the sweetest sinecures in the economy. Their humanity, meaning their ability to individualize services and connect with others, which computers lack, adds value. Yet not only does AI win at cards now, it also creates art, writes poetry, and performs psychotherapy. Even lovemaking is at risk, as artificially intelligent robots stand poised to enter the market and provide sexual services and romantic intimacy.

More here.

Lord Byron, according to his dumped mistress Lady Caroline Lamb, was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”. Antony Peattie’s exploration of his personal caprices and intellectual quirks definitively strikes down all three charges. Byron the self-aware ironist was never demented; he may have relished his reputation for vice, but his pagan promiscuity was overshadowed by the legacy of his punitive Calvinist upbringing; and it would surely have been a delight, not a danger, to know this convivial fellow, whose eyes, as Coleridge said, were “the open portals of the sun” and his teeth “so many stationary smiles”.

Lord Byron, according to his dumped mistress Lady Caroline Lamb, was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”. Antony Peattie’s exploration of his personal caprices and intellectual quirks definitively strikes down all three charges. Byron the self-aware ironist was never demented; he may have relished his reputation for vice, but his pagan promiscuity was overshadowed by the legacy of his punitive Calvinist upbringing; and it would surely have been a delight, not a danger, to know this convivial fellow, whose eyes, as Coleridge said, were “the open portals of the sun” and his teeth “so many stationary smiles”. The four impossible “problems of antiquity”—

The four impossible “problems of antiquity”— Silence and endings are much on Howe’s mind these days. She is seventy-nine, slight but still spry, with a kind, angular face and sharp blue eyes. She has a puckish sense of humor: her friend, the philosopher Richard Kearney, described her to me as a “comic mystic, or a mystic comic.” The coffee shop I originally suggested was closed for the day. On our walk to the Fogg, she told me, in a voice that still recalls the 1950s Cambridge milieu in which she grew up, about her recent trip to Belfast and how much she’d loved

Silence and endings are much on Howe’s mind these days. She is seventy-nine, slight but still spry, with a kind, angular face and sharp blue eyes. She has a puckish sense of humor: her friend, the philosopher Richard Kearney, described her to me as a “comic mystic, or a mystic comic.” The coffee shop I originally suggested was closed for the day. On our walk to the Fogg, she told me, in a voice that still recalls the 1950s Cambridge milieu in which she grew up, about her recent trip to Belfast and how much she’d loved

I’ve been saying it for years! Every fall, the big night would come and I would set my alarm for four or six or eight in the morning, depending on my time zone, and then not sleep because I was sure Olga Tokarczuk would win the Nobel Prize in Literature. This year it happened! At 4 A.M.

I’ve been saying it for years! Every fall, the big night would come and I would set my alarm for four or six or eight in the morning, depending on my time zone, and then not sleep because I was sure Olga Tokarczuk would win the Nobel Prize in Literature. This year it happened! At 4 A.M. I have always admired John le Carré. Not always without envy – so many bestsellers! – but in wonderment at the fact that the work of an artist of such high literary accomplishment should have achieved such wide appeal among readers. That le Carré, otherwise David Cornwell, has chosen to set his novels almost exclusively in the world of espionage has allowed certain critics to dismiss him as essentially unserious, a mere entertainer. But with at least two of his books,

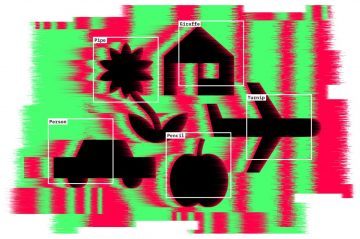

I have always admired John le Carré. Not always without envy – so many bestsellers! – but in wonderment at the fact that the work of an artist of such high literary accomplishment should have achieved such wide appeal among readers. That le Carré, otherwise David Cornwell, has chosen to set his novels almost exclusively in the world of espionage has allowed certain critics to dismiss him as essentially unserious, a mere entertainer. But with at least two of his books,  A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’. Such an event hasn’t actually happened, but the potential for sabotaging AI is very real. Researchers have already demonstrated

A self-driving car approaches a stop sign, but instead of slowing down, it accelerates into the busy intersection. An accident report later reveals that four small rectangles had been stuck to the face of the sign. These fooled the car’s onboard artificial intelligence (AI) into misreading the word ‘stop’ as ‘speed limit 45’. Such an event hasn’t actually happened, but the potential for sabotaging AI is very real. Researchers have already demonstrated  The Polish novelist and activist Olga Tokarczuk and the controversial Austrian author Peter Handke have both won the

The Polish novelist and activist Olga Tokarczuk and the controversial Austrian author Peter Handke have both won the  There is no agreed criterion to distinguish science from pseudoscience, or just plain ordinary bullshit, opening the door to all manner of metaphysics masquerading as science. This is ‘post-empirical’ science, where truth no longer matters, and it is potentially very dangerous.

There is no agreed criterion to distinguish science from pseudoscience, or just plain ordinary bullshit, opening the door to all manner of metaphysics masquerading as science. This is ‘post-empirical’ science, where truth no longer matters, and it is potentially very dangerous. A parade of American presidents on the left and the right argued that by cultivating China as a market — hastening its economic growth and technological sophistication while bringing our own companies a billion new workers and customers — we would inevitably loosen the regime’s hold on its people. Even Donald Trump, who made bashing China a theme of his campaign, sees the country mainly through the lens of markets. He’ll eagerly prosecute a pointless trade war against China, but when it comes to the millions in Hong Kong who are protesting China’s creeping despotism over their territory,

A parade of American presidents on the left and the right argued that by cultivating China as a market — hastening its economic growth and technological sophistication while bringing our own companies a billion new workers and customers — we would inevitably loosen the regime’s hold on its people. Even Donald Trump, who made bashing China a theme of his campaign, sees the country mainly through the lens of markets. He’ll eagerly prosecute a pointless trade war against China, but when it comes to the millions in Hong Kong who are protesting China’s creeping despotism over their territory,  There are many debutante balls in Texas, and a number of pageants that feature historical costumes, but the Society of Martha Washington Colonial Pageant and Ball in Laredo is the most opulently patriotic among them. In the late 1840s, a number of European American settlers from the East were sent to staff a new military base in southwest Texas, a region that had recently been ceded to the United States after the Mexican-American War. They found themselves in a place that was tenuously and unenthusiastically American. Feeling perhaps a little forlorn at being so starkly in the minority, these new arrivals established a local chapter of the lamentably named Improved Order of Red Men. (Members of the order dressed as “Indians,” called their officers “chiefs,” and began their meetings, or “powwows,” by banging a tomahawk instead of a gavel.)

There are many debutante balls in Texas, and a number of pageants that feature historical costumes, but the Society of Martha Washington Colonial Pageant and Ball in Laredo is the most opulently patriotic among them. In the late 1840s, a number of European American settlers from the East were sent to staff a new military base in southwest Texas, a region that had recently been ceded to the United States after the Mexican-American War. They found themselves in a place that was tenuously and unenthusiastically American. Feeling perhaps a little forlorn at being so starkly in the minority, these new arrivals established a local chapter of the lamentably named Improved Order of Red Men. (Members of the order dressed as “Indians,” called their officers “chiefs,” and began their meetings, or “powwows,” by banging a tomahawk instead of a gavel.) L

L So why are publishers suddenly bending over backwards to fill their schedules with people of colour? Interviewing a range of writers, publishers and other industry professionals throws up complex and sometimes disturbing answers. It’s certainly not only about capitalizing on a trend. Sharmaine Lovegrove, publisher of the Little, Brown imprint Dialogue Books, tells me that it’s partly the result of an evolving culture of shame and embarrassment: “Agents are asking people who have a little bit of a social media presence to come up quite quickly with ideas that they can sell to publishers who are desperate because no list wants to be all white, as it has been”. With the dread of being associated with the hashtag #publishingsowhite, the simplest and cheapest way of adding black names to their lists is to put out anthologies packed with malleable first-time authors and one or two seasoned writers seeded through the collections. (A – presumably – more expensive way is to recruit Stormzy, who launched the #Merky Books imprint at Penguin Random House last year.)

So why are publishers suddenly bending over backwards to fill their schedules with people of colour? Interviewing a range of writers, publishers and other industry professionals throws up complex and sometimes disturbing answers. It’s certainly not only about capitalizing on a trend. Sharmaine Lovegrove, publisher of the Little, Brown imprint Dialogue Books, tells me that it’s partly the result of an evolving culture of shame and embarrassment: “Agents are asking people who have a little bit of a social media presence to come up quite quickly with ideas that they can sell to publishers who are desperate because no list wants to be all white, as it has been”. With the dread of being associated with the hashtag #publishingsowhite, the simplest and cheapest way of adding black names to their lists is to put out anthologies packed with malleable first-time authors and one or two seasoned writers seeded through the collections. (A – presumably – more expensive way is to recruit Stormzy, who launched the #Merky Books imprint at Penguin Random House last year.) In May 1949, a year after the establishment of the state of Israel, the American Jewish literary critic Leslie Fiedler published in Commentary an essay about the fundamental challenge facing American Jewish writers: that is, novelists, poets, and intellectuals like Fiedler himself. Entitled “What Can We Do About Fagin?”—Fagin being the Jewish villain of Charles Dickens’s novel Oliver Twist—the essay shows that the modern Jew who adopts English as his language is joining a culture riddled with negative stereotypes of . . . himself. These demonic images figure in some of the best works of some of the best writers, and form an indelible part of the English literary tradition—not just in the earlier form of Dickens’ Fagin, or still earlier of Shakespeare’s Shylock, but in, to mention only two famous modern poets, Ezra Pound’s wartime broadcasts inveighing against “Jew slime” or such memorable lines by T.S. Eliot as “The rats are underneath the piles. The jew is underneath the lot” and the same venerated poet’s 1933 admonition that, in any well-ordered society, “reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable.”

In May 1949, a year after the establishment of the state of Israel, the American Jewish literary critic Leslie Fiedler published in Commentary an essay about the fundamental challenge facing American Jewish writers: that is, novelists, poets, and intellectuals like Fiedler himself. Entitled “What Can We Do About Fagin?”—Fagin being the Jewish villain of Charles Dickens’s novel Oliver Twist—the essay shows that the modern Jew who adopts English as his language is joining a culture riddled with negative stereotypes of . . . himself. These demonic images figure in some of the best works of some of the best writers, and form an indelible part of the English literary tradition—not just in the earlier form of Dickens’ Fagin, or still earlier of Shakespeare’s Shylock, but in, to mention only two famous modern poets, Ezra Pound’s wartime broadcasts inveighing against “Jew slime” or such memorable lines by T.S. Eliot as “The rats are underneath the piles. The jew is underneath the lot” and the same venerated poet’s 1933 admonition that, in any well-ordered society, “reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable.” On 25 April 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick announced

On 25 April 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick announced