Robert Pollack in Edge:

How do we understand that our 100,000-fold excess of numbers on this planet, plus what we do to feed ourselves, makes us a tumor on the body of the planet? I don’t want the future that involves some end to us, which is a kind of surgery of the planet. That’s not anybody’s wish. How do we revert ourselves to normal while we can? How do we re-enter the world of natural selection, not by punishing each other, but by volunteering to take success as meaning success and survival of the future, not success in stuff now? How do we do that? We don’t have a language for that.

How do we understand that our 100,000-fold excess of numbers on this planet, plus what we do to feed ourselves, makes us a tumor on the body of the planet? I don’t want the future that involves some end to us, which is a kind of surgery of the planet. That’s not anybody’s wish. How do we revert ourselves to normal while we can? How do we re-enter the world of natural selection, not by punishing each other, but by volunteering to take success as meaning success and survival of the future, not success in stuff now? How do we do that? We don’t have a language for that.

(ROBERT POLLACK is a professor of biological sciences, and also serves as director of the University Seminars at Columbia University.)

I’m asking myself what’s most important to do in the time I have. I’m very grateful for the time I have. I’m astounded at the difference between where I am and where I was in my memory, and astounded at the absence of a future stability to meet the stability that I had when I was growing up.

I was born in 1940. I’ve lived through the period of the greatest hegemony of American power and democracy and military might, with you and everybody else my age. We’ve lived seventy years without a nuclear war, after the use of nuclear weapons once. I look at my students who have remained the same age for the forty years I’ve been teaching them as I’ve gotten forty years older, and I wonder what their lives will be when they’re my age, what their grandchildren’s lives will be. That’s what’s on my mind. I don’t think it’s a political question at all. It’s an existential question. It may be a religious question. It is certainly an emotionally driven question. I’m a scientist, so I guess I have to say as well that it’s a scientific question. When I think about it as a scientific question, I think about it in terms of my work.

More here.

Tech mogul Marc Benioff has been winning media accolades for his declaration that “capitalism, as we know it, is dead.” The billionaire founder and CEO of Salesforce, a cloud-based customer-relations company, has launched an advertising blitz promoting his new book, Trailblazer, which calls for a “more fair, equal and sustainable capitalism,” as Benioff put it in a New York Times op-ed on Monday. This “new capitalism” would not “just take from society but truly give back and have a positive impact,” Benioff maintains.

Tech mogul Marc Benioff has been winning media accolades for his declaration that “capitalism, as we know it, is dead.” The billionaire founder and CEO of Salesforce, a cloud-based customer-relations company, has launched an advertising blitz promoting his new book, Trailblazer, which calls for a “more fair, equal and sustainable capitalism,” as Benioff put it in a New York Times op-ed on Monday. This “new capitalism” would not “just take from society but truly give back and have a positive impact,” Benioff maintains.

Throughout my career as a neurosurgeon, I have worked closely with oncologists. Many of my patients have cancer of the brain — one of the deadliest of the near-infinite number of cancers. I have always viewed my oncological colleagues with complicated, contradictory feelings. On the one hand, I’m in awe of their work, which can be so emotionally demanding. On the other, I suspect they don’t always know when to stop.

Throughout my career as a neurosurgeon, I have worked closely with oncologists. Many of my patients have cancer of the brain — one of the deadliest of the near-infinite number of cancers. I have always viewed my oncological colleagues with complicated, contradictory feelings. On the one hand, I’m in awe of their work, which can be so emotionally demanding. On the other, I suspect they don’t always know when to stop. Unlike Hillary Clinton, who used the same title for her memoir,

Unlike Hillary Clinton, who used the same title for her memoir,  In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option.

In New York, where I live, whenever there’s a big holiday weekend, the traffic on Friday as folks leave town turns much of Manhattan into a hot, fume-filled parking lot. On those days, one can often walk faster than the traffic is moving. That may be the exception, but congestion in many cities has reached the point where getting around by car at certain times of day is almost not an option. FOR THE AUTUMNAL EQUINOX OF 1967

FOR THE AUTUMNAL EQUINOX OF 1967 Of all the ways that human beings differ from the rest of what is found in nature, being able to think is most fundamental. Being able to think is, it seems, uniquely characteristic of us. But what is so special about the ability to think? In other words, what is so special about us? Analytic philosophy finds its foundations in an answer: not very much. An elusive new book, Thinking and Being, by Irad Kimhi, a heretofore little-known Israeli philosopher, argues that this is the wrong answer. And so, he argues, a whole tradition of philosophical thought is wrong, not just in the details, but in the fundamentals. What Kimhi wants to show is that the logical features of thought, and so also the features of those who think them, stand at a far remove from anything we might now call “natural.”

Of all the ways that human beings differ from the rest of what is found in nature, being able to think is most fundamental. Being able to think is, it seems, uniquely characteristic of us. But what is so special about the ability to think? In other words, what is so special about us? Analytic philosophy finds its foundations in an answer: not very much. An elusive new book, Thinking and Being, by Irad Kimhi, a heretofore little-known Israeli philosopher, argues that this is the wrong answer. And so, he argues, a whole tradition of philosophical thought is wrong, not just in the details, but in the fundamentals. What Kimhi wants to show is that the logical features of thought, and so also the features of those who think them, stand at a far remove from anything we might now call “natural.” This shattering, sometimes unbearably powerful novel, completed in 1904, was written by Henrik Pontoppidan, who won the Nobel Prize in 1917. It is considered one of the greatest Danish novels; the filmmaker Bille August turned the story into a nearly three-hour movie called, in English, “A Fortunate Man” (2019). The novel was praised by Thomas Mann and Ernst Bloch, and is effectively at the center of Georg Lukács’s classic study “

This shattering, sometimes unbearably powerful novel, completed in 1904, was written by Henrik Pontoppidan, who won the Nobel Prize in 1917. It is considered one of the greatest Danish novels; the filmmaker Bille August turned the story into a nearly three-hour movie called, in English, “A Fortunate Man” (2019). The novel was praised by Thomas Mann and Ernst Bloch, and is effectively at the center of Georg Lukács’s classic study “

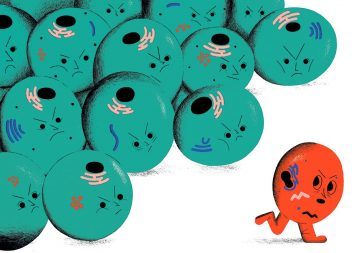

Yasuyaki Fujita has seen first-hand what happens when cells stop being polite and start getting real. He caught a glimpse of this harsh microscopic world when he switched on a cancer-causing gene called Ras in a few kidney cells in a dish. He expected to see the cancerous cells expanding and forming the beginnings of tumours among their neighbours. Instead, the neat, orderly neighbours armed themselves with filament proteins and started “poking, poking, poking”, says Fujita, a cancer biologist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. “The transformed cells were eliminated from the society of normal cells,” he says, literally pushed out by the cells next door.

Yasuyaki Fujita has seen first-hand what happens when cells stop being polite and start getting real. He caught a glimpse of this harsh microscopic world when he switched on a cancer-causing gene called Ras in a few kidney cells in a dish. He expected to see the cancerous cells expanding and forming the beginnings of tumours among their neighbours. Instead, the neat, orderly neighbours armed themselves with filament proteins and started “poking, poking, poking”, says Fujita, a cancer biologist at Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan. “The transformed cells were eliminated from the society of normal cells,” he says, literally pushed out by the cells next door.

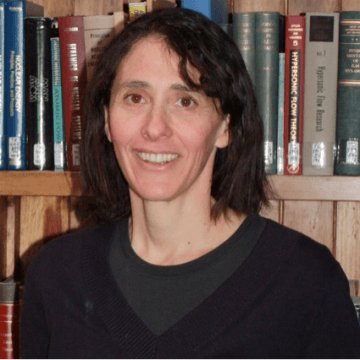

Artificial intelligence is better than humans at playing chess or go, but still has trouble holding a conversation or driving a car. A simple way to think about the discrepancy is through the lens of “common sense” — there are features of the world, from the fact that tables are solid to the prediction that a tree won’t walk across the street, that humans take for granted but that machines have difficulty learning. Melanie Mitchell is a computer scientist and complexity researcher who has written a new book about the prospects of modern AI. We talk about deep learning and other AI strategies, why they currently fall short at equipping computers with a functional “folk physics” understanding of the world, and how we might move forward.

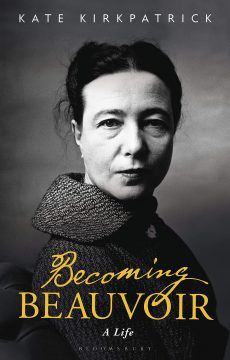

Artificial intelligence is better than humans at playing chess or go, but still has trouble holding a conversation or driving a car. A simple way to think about the discrepancy is through the lens of “common sense” — there are features of the world, from the fact that tables are solid to the prediction that a tree won’t walk across the street, that humans take for granted but that machines have difficulty learning. Melanie Mitchell is a computer scientist and complexity researcher who has written a new book about the prospects of modern AI. We talk about deep learning and other AI strategies, why they currently fall short at equipping computers with a functional “folk physics” understanding of the world, and how we might move forward. Writers always have to make difficult choices about what to leave in and what to cut from their work. The choices become especially acute when a writer is telling her own story. “What an odd thing a diary is,” a character in Simone de Beauvoir’s novel The Woman Destroyed (La Femme rompue, 1967) says, “the things you omit are more important than those you put in.”

Writers always have to make difficult choices about what to leave in and what to cut from their work. The choices become especially acute when a writer is telling her own story. “What an odd thing a diary is,” a character in Simone de Beauvoir’s novel The Woman Destroyed (La Femme rompue, 1967) says, “the things you omit are more important than those you put in.” In a bone-picking mood,

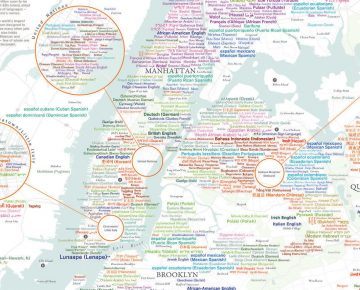

In a bone-picking mood, Reawakening dormant languages requires extraordinary acts of coordination—administrative, social, and emotional—but it is possible. Take jessie “little doe” baird, a Wôpanâak woman who, when pregnant with her fifth child, Mae Alice, had a vision of reviving her ancestral language—the first tongue the Pilgrims encountered in coastal Massachusetts, which had been without speakers for more than a century. baird studied linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then spent the next twenty-six years leading a revival of Wôpanâak; Mae Alice is the first Wôpanâak-speaking child in generations. In Ohio, activist Daryl Baldwin has spearheaded the revival of Myaamia, dormant since the 1960s, first teaching it to himself, his wife, and their four children. Common to both community-led efforts was meticulous linguistic research that fed into the creation of immersion programs focused on fostering fluent new speakers.

Reawakening dormant languages requires extraordinary acts of coordination—administrative, social, and emotional—but it is possible. Take jessie “little doe” baird, a Wôpanâak woman who, when pregnant with her fifth child, Mae Alice, had a vision of reviving her ancestral language—the first tongue the Pilgrims encountered in coastal Massachusetts, which had been without speakers for more than a century. baird studied linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then spent the next twenty-six years leading a revival of Wôpanâak; Mae Alice is the first Wôpanâak-speaking child in generations. In Ohio, activist Daryl Baldwin has spearheaded the revival of Myaamia, dormant since the 1960s, first teaching it to himself, his wife, and their four children. Common to both community-led efforts was meticulous linguistic research that fed into the creation of immersion programs focused on fostering fluent new speakers.