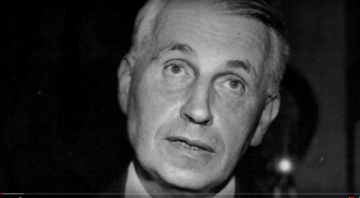

Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee is a physician-scientist with a persistent scientific and clinical interest in acute myeloid leukemia, hematopoiesis, novel therapeutic drug development and cancer biology. He is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. He has published articles in Nature, The New England Journal of Medicine, The New York Times, and Cell. Dr. Mukherjee’s research lab at Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center studies the biology of blood development malignant and premalignant diseases such as myelodysplasia and acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). His goal is to develop new drugs against diseases. He currently serves as an Associate Professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center.

Azra Raza, author of The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

I could not believe my luck when I woke up this morning. It had rained last night, but this morning the sky was blue the breeze gentle,and the wild grass along the smelly sluggish, open sewer that meanders through the swanky Defense Housing Authority—home to lush golf courses and palatial villas—past the gates of the elite Lahore University of Management Sciences, was audaciously green. The mango tree in the front yard of my mother’s house—quiet after a fertile summer of exuberant fruiting—balances the crow’s nest full of chattering chicks in its gently swaying branches. All God’s creations bask in the mellow sunshine. No more the snow and ice and cold of Eastern US. For these weeks, it’s going to be this bliss in Lahore. I was glad to be me, and to be alive. I say to myself “Thank God I am on this side of the earth, rather than under it.” What a beautiful world. So much to see and so much to do. I could live like this for a hundred years like William Hazlitt, who claimed to have spent his life “reading books, looking at pictures, going to plays, hearing, thinking, writing on what pleased me best.” I’ll add eating to that list, at the top of it, fried eggs and buttered toast.

I could not believe my luck when I woke up this morning. It had rained last night, but this morning the sky was blue the breeze gentle,and the wild grass along the smelly sluggish, open sewer that meanders through the swanky Defense Housing Authority—home to lush golf courses and palatial villas—past the gates of the elite Lahore University of Management Sciences, was audaciously green. The mango tree in the front yard of my mother’s house—quiet after a fertile summer of exuberant fruiting—balances the crow’s nest full of chattering chicks in its gently swaying branches. All God’s creations bask in the mellow sunshine. No more the snow and ice and cold of Eastern US. For these weeks, it’s going to be this bliss in Lahore. I was glad to be me, and to be alive. I say to myself “Thank God I am on this side of the earth, rather than under it.” What a beautiful world. So much to see and so much to do. I could live like this for a hundred years like William Hazlitt, who claimed to have spent his life “reading books, looking at pictures, going to plays, hearing, thinking, writing on what pleased me best.” I’ll add eating to that list, at the top of it, fried eggs and buttered toast.

American writer Rebecca Solnit laments that few writers have had quite as much scrutiny directed toward their laundry habits as Transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau, best known for his 1854 memoir Walden. “Only Henry David Thoreau,” she claims in Orion Magazine’s article “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved,” “has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.”

American writer Rebecca Solnit laments that few writers have had quite as much scrutiny directed toward their laundry habits as Transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau, best known for his 1854 memoir Walden. “Only Henry David Thoreau,” she claims in Orion Magazine’s article “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved,” “has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.” Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.  Like other teachers and sages I’d known and apprenticed myself to for seasons of my life, Bloom performed, but what he didn’t perform was pedagogy or teaching, not for himself and not for us. He just did readings, in the Bloom way, which was an ongoing drama, in words, between the work at hand and the absent works, lines and phrases that the work had brought itself into being from. This isn’t the same as watered down “intertextuality” or “influence studies” or, god forbid, some kind of seminar or salon-like conversation. It wasn’t “New Critical” thing-in-itself close reading, because poems weren’t things in themselves, they were living subjects, and as full of contradictions and private dramas and unconscious desires and hauntings as any other. While some critics thought about the “political unconscious” and others of just the human unconscious, Bloom found a way to surface the poetic unconscious.

Like other teachers and sages I’d known and apprenticed myself to for seasons of my life, Bloom performed, but what he didn’t perform was pedagogy or teaching, not for himself and not for us. He just did readings, in the Bloom way, which was an ongoing drama, in words, between the work at hand and the absent works, lines and phrases that the work had brought itself into being from. This isn’t the same as watered down “intertextuality” or “influence studies” or, god forbid, some kind of seminar or salon-like conversation. It wasn’t “New Critical” thing-in-itself close reading, because poems weren’t things in themselves, they were living subjects, and as full of contradictions and private dramas and unconscious desires and hauntings as any other. While some critics thought about the “political unconscious” and others of just the human unconscious, Bloom found a way to surface the poetic unconscious. Warning: this story is about death. You might want to click away now.

Warning: this story is about death. You might want to click away now. Is a penchant for moral posturing part of a newspaper columnist’s job description? Sometimes it seems so. But if there were a prize for self-indulgent journalistic garment renting, Bret Stephens of The New York Times would certainly retire the trophy.

Is a penchant for moral posturing part of a newspaper columnist’s job description? Sometimes it seems so. But if there were a prize for self-indulgent journalistic garment renting, Bret Stephens of The New York Times would certainly retire the trophy.  The question that I’ve been perplexed by for a long time has to do with moral motivation. Where does it come from? Is moral motivation unique to the human animal or are there others? It’s clear at this point that moral motivation is part of what we are genetically equipped with, and that we share this with mammals, in general, and birds. In the case of humans, our moral behavior is more complex, which is probably because we have bigger brains. We have more neurons than, say, a chimpanzee, a mouse, or a rat, but we have all the same structures. There is no special structure for morality tucked in there.

The question that I’ve been perplexed by for a long time has to do with moral motivation. Where does it come from? Is moral motivation unique to the human animal or are there others? It’s clear at this point that moral motivation is part of what we are genetically equipped with, and that we share this with mammals, in general, and birds. In the case of humans, our moral behavior is more complex, which is probably because we have bigger brains. We have more neurons than, say, a chimpanzee, a mouse, or a rat, but we have all the same structures. There is no special structure for morality tucked in there. The idea for the Aspen Institute first emerged after the second world war. In 1949 Walter Paepcke, a Chicago businessman, planned a bicentennial celebration of the life of Goethe. Paepcke and his wife, Elizabeth, chose Aspen because it was both beautiful and easily accessible from either coast. The couple felt there was an “urgent need” to understand Goethe’s thought: the world, still recovering from the war, had been cleft in half by the ideological battle between communism and capitalism. The Paepckes saw Goethe as a prime advocate of the underlying unity of mankind. He also worried about the corrosive effects of rapidly proliferating wealth. The Paepckes imagined that Aspen could become an “American Athens”, educating an upper-crust elite hungry for spiritual sustenance in the newly ascendant nation. Such work was vital “if the people of America and other nations are to strengthen their will for decency, ethical conduct and morality in a modern world”. Herbert Hoover, the former president, was named honorary chairman; Thomas Mann joined the board of directors.

The idea for the Aspen Institute first emerged after the second world war. In 1949 Walter Paepcke, a Chicago businessman, planned a bicentennial celebration of the life of Goethe. Paepcke and his wife, Elizabeth, chose Aspen because it was both beautiful and easily accessible from either coast. The couple felt there was an “urgent need” to understand Goethe’s thought: the world, still recovering from the war, had been cleft in half by the ideological battle between communism and capitalism. The Paepckes saw Goethe as a prime advocate of the underlying unity of mankind. He also worried about the corrosive effects of rapidly proliferating wealth. The Paepckes imagined that Aspen could become an “American Athens”, educating an upper-crust elite hungry for spiritual sustenance in the newly ascendant nation. Such work was vital “if the people of America and other nations are to strengthen their will for decency, ethical conduct and morality in a modern world”. Herbert Hoover, the former president, was named honorary chairman; Thomas Mann joined the board of directors. In the depths of winter, water temperatures in the ice-covered Arctic Ocean can sink below zero. That’s cold enough to freeze many fish, but the conditions don’t trouble the cod. A protein in its blood and tissues binds to tiny ice crystals and stops them from growing. Where codfish got this talent was a puzzle that evolutionary biologist Helle Tessand Baalsrud wanted to solve. She and her team at the University of Oslo searched the genomes of the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and several of its closest relatives, thinking they would track down the cousins of the antifreeze gene. None showed up. Baalsrud, who at the time was a new parent, worried that her lack of sleep was causing her to miss something obvious.

In the depths of winter, water temperatures in the ice-covered Arctic Ocean can sink below zero. That’s cold enough to freeze many fish, but the conditions don’t trouble the cod. A protein in its blood and tissues binds to tiny ice crystals and stops them from growing. Where codfish got this talent was a puzzle that evolutionary biologist Helle Tessand Baalsrud wanted to solve. She and her team at the University of Oslo searched the genomes of the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and several of its closest relatives, thinking they would track down the cousins of the antifreeze gene. None showed up. Baalsrud, who at the time was a new parent, worried that her lack of sleep was causing her to miss something obvious. Ethan Weinstein in 3:AM Magazine:

Ethan Weinstein in 3:AM Magazine: Astra Taylor in the New York Times:

Astra Taylor in the New York Times: