Peter Salmon in New Humanist:

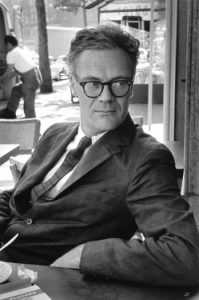

On 24 July 1967, the poet Paul Celan gave a reading in Freiburg im Brisgau. At the time he was on a leave of absence from Saint-Anne psychiatric hospital, where he had been interned after suffering a nervous breakdown, in the midst of which he attempted suicide. At the reading was the philosopher Martin Heidegger. The day after the reading Celan was invited to a meeting with Heidegger at the philosopher’s hut. On arrival Celan signed the guestbook, then the two men went for a walk, which was curtailed by rain, and were driven back to the hut. After their brief meeting Celan returned to Saint-Anne’s. One week later, on 1 August, Celan wrote a poem about the encounter in the form of a single, oblique sentence named after the place where Heidegger’s hut stood, “Todtnauberg”. The title contained two words crucial to both the the poetry of Celan and the philosophy of Heidegger – berg meaning mountain, and todt, death.

On 24 July 1967, the poet Paul Celan gave a reading in Freiburg im Brisgau. At the time he was on a leave of absence from Saint-Anne psychiatric hospital, where he had been interned after suffering a nervous breakdown, in the midst of which he attempted suicide. At the reading was the philosopher Martin Heidegger. The day after the reading Celan was invited to a meeting with Heidegger at the philosopher’s hut. On arrival Celan signed the guestbook, then the two men went for a walk, which was curtailed by rain, and were driven back to the hut. After their brief meeting Celan returned to Saint-Anne’s. One week later, on 1 August, Celan wrote a poem about the encounter in the form of a single, oblique sentence named after the place where Heidegger’s hut stood, “Todtnauberg”. The title contained two words crucial to both the the poetry of Celan and the philosophy of Heidegger – berg meaning mountain, and todt, death.

What was discussed on their walk is not known – some have speculated they discussed their shared interest in botany, while other accounts suggest that Heidegger talked about his recent interview with the magazine Der Spiegel. But it is what was not discussed, between a Jewish poet who survived the Holocaust and a philosopher who was one of the highest-profile sympathisers of Nazism, that has continued to resonate for more than 50 years.

Paul Celan was born Paul Antschel (Celan is a reversal of the two syllables) in 1920, into a German-speaking Jewish family in Bukovina in Romania. His father, Leo, was a Zionist, who insisted his son learn Hebrew, while his mother, Fritzl, insisted, as a devotee of German literature, that German be the language spoken at home. After briefly studying medicine in Tours, France – a Jewish quota made it impossible for him to study in Romania – he returned to Bukovina in 1939. His journey to France had taken him through Berlin, where, from the train, he saw plumes of smoke rising the day after Kristallnacht. Under German occupation in Bukovina, Celan was interned in a ghetto, writing poetry and translating Shakespeare’s sonnets while being forced to gather and destroy Russian books. In a life shot through with historical symbolism, the significance of these simultaneous acts seems terrifyingly apt.

More here.

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens.

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens. This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

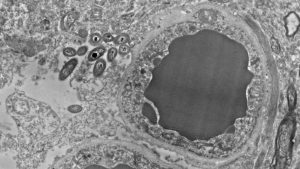

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The Pioneer Valley in western Massachusetts is a cradle of social progress — a place where L.G.B.T.Q. is often followed by I.A. (for intersex and asexual), there’s a Stonewall Center (now 33 years old), and gender-nonconforming parents have a nickname of choice (it’s “Baba”).

The Pioneer Valley in western Massachusetts is a cradle of social progress — a place where L.G.B.T.Q. is often followed by I.A. (for intersex and asexual), there’s a Stonewall Center (now 33 years old), and gender-nonconforming parents have a nickname of choice (it’s “Baba”). In a publication

In a publication On the evening of 28 October, as they absorbed the election of far-right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, British leftists declared “socialism or barbarism”. The slogan was assumed by some to be a Corbynite coinage. But it was first popularised more than a century ago in war-ravaged Europe.

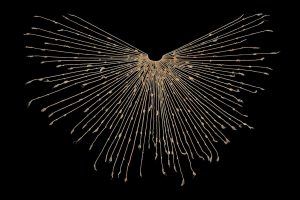

On the evening of 28 October, as they absorbed the election of far-right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, British leftists declared “socialism or barbarism”. The slogan was assumed by some to be a Corbynite coinage. But it was first popularised more than a century ago in war-ravaged Europe. The Incas left no doubt that theirs was a sophisticated, technologically savvy civilisation. At its height in the 15th century, it was the largest empire in the Americas, extending almost 5000 kilometres from modern-day Ecuador to Chile. These were the people who built Machu Picchu, a royal estate perched in the clouds, and an extensive network of paved roads complete with suspension bridges crafted from woven grass. But the paradox of the Incas is that despite all this sophistication they never learned to write.

The Incas left no doubt that theirs was a sophisticated, technologically savvy civilisation. At its height in the 15th century, it was the largest empire in the Americas, extending almost 5000 kilometres from modern-day Ecuador to Chile. These were the people who built Machu Picchu, a royal estate perched in the clouds, and an extensive network of paved roads complete with suspension bridges crafted from woven grass. But the paradox of the Incas is that despite all this sophistication they never learned to write. Before ancient humans

Before ancient humans