From The New York Times:

“A geneticist, an oncologist, a roboticist, a novelist and an A.I. researcher walk into a bar.” That could be the setup for a very bad joke — or a tremendously fascinating conversation. Fortunately for us, it was the latter. On a blustery evening in late September, in a private room at a bar near Times Square, the magazine gathered five brilliant scientists and thinkers around a table for a three-hour dinner. In the (edited) transcript below — moderated by Mark Jannot, a story editor at the magazine and a former editor in chief of Popular Science — you can see what they had to say about the future of medicine, health care and humanity.

“A geneticist, an oncologist, a roboticist, a novelist and an A.I. researcher walk into a bar.” That could be the setup for a very bad joke — or a tremendously fascinating conversation. Fortunately for us, it was the latter. On a blustery evening in late September, in a private room at a bar near Times Square, the magazine gathered five brilliant scientists and thinkers around a table for a three-hour dinner. In the (edited) transcript below — moderated by Mark Jannot, a story editor at the magazine and a former editor in chief of Popular Science — you can see what they had to say about the future of medicine, health care and humanity.

I. WILL WE ENGINEER OUR CHILDREN, AND OURSELVES?

MARK JANNOT: For years, many pregnant women have undergone amniocentesis to test for rare metabolic disorders and other fetal issues. And couples who use in vitro fertilization can screen the embryos for genetic abnormalities. What sorts of advances in genetic screening and manipulation are coming, and where do you see that taking us?

CATHERINE MOHR: When I was pregnant with my daughter, my husband and I were joking, “Well, if she gets the best of both of us, she’ll be a superhero, and if she gets the worst of both of us, she’s not going to make it out of first grade.” And so we were rolling the genetic dice, which you do when you choose to have a child.

More here.

A couple of years ago, while working on my novel Home Fire, which required me to look into certain aspects of the UK’s citizenship laws, I had a slightly painful conversation with one of my oldest friends. Like me, she had grown up in Karachi. But while I didn’t move to the UK until the age of 34, she came here at 18 to go to university, and has never left. She became a British citizen soon after graduating (her grandmother was British); later, she married an Englishman, and they had a son. Her son was born in London, has never lived anywhere but here. But the painful thing I had to tell her was this: unlike many children who are born and live in the UK, her son’s claim on UK citizenship was contingent rather than assured. He was a British citizen, yes, but he could be made unBritish.

A couple of years ago, while working on my novel Home Fire, which required me to look into certain aspects of the UK’s citizenship laws, I had a slightly painful conversation with one of my oldest friends. Like me, she had grown up in Karachi. But while I didn’t move to the UK until the age of 34, she came here at 18 to go to university, and has never left. She became a British citizen soon after graduating (her grandmother was British); later, she married an Englishman, and they had a son. Her son was born in London, has never lived anywhere but here. But the painful thing I had to tell her was this: unlike many children who are born and live in the UK, her son’s claim on UK citizenship was contingent rather than assured. He was a British citizen, yes, but he could be made unBritish. It is an understatement to say that the 42-year-old [Tino] Sehgal is obsessive about his work, from its concept to the lexicon used to describe it. His practice has more to do with theater and acting techniques (many of his players are professional actors) than it does with the tradition of performance art, the de facto description for any kind of live experimentation in the art world. And it’s not strictly conceptual art, either, if one goes by

It is an understatement to say that the 42-year-old [Tino] Sehgal is obsessive about his work, from its concept to the lexicon used to describe it. His practice has more to do with theater and acting techniques (many of his players are professional actors) than it does with the tradition of performance art, the de facto description for any kind of live experimentation in the art world. And it’s not strictly conceptual art, either, if one goes by  The executive summary of the paper is this. They claim that the optical signal does not fit with the hypothesis that the event is a neutron-star merger. Instead, they argue, it looks like a specific type of white-dwarf merger. A white-dwarf merger, however, would not result in a gravitational wave signal strong enough to be measurable by LIGO. So, they conclude, there must be something wrong with the LIGO event. (The VIRGO measurement of that event has a signal-to-noise ratio of merely two, so it doesn’t increase the significance all that much.)

The executive summary of the paper is this. They claim that the optical signal does not fit with the hypothesis that the event is a neutron-star merger. Instead, they argue, it looks like a specific type of white-dwarf merger. A white-dwarf merger, however, would not result in a gravitational wave signal strong enough to be measurable by LIGO. So, they conclude, there must be something wrong with the LIGO event. (The VIRGO measurement of that event has a signal-to-noise ratio of merely two, so it doesn’t increase the significance all that much.) PANKAJ MISHRA: I know from experience that it is very easy for a brown-skinned Indian writer to be caricatured as a knee-jerk anti-American/anti-Westernist/Third-Worldist/angry postcolonial, and it is important then to point out that my understanding of modern imperialism and liberalism — like that of many people with my background — is actually grounded in an experience of Indian political realities.

PANKAJ MISHRA: I know from experience that it is very easy for a brown-skinned Indian writer to be caricatured as a knee-jerk anti-American/anti-Westernist/Third-Worldist/angry postcolonial, and it is important then to point out that my understanding of modern imperialism and liberalism — like that of many people with my background — is actually grounded in an experience of Indian political realities. It is the mind of the writer that makes for the most brilliant essays. Reality—whether the material world of our senses or the intellectual world we apprehend—is of intrinsic interest. It exists, according to some thinkers, eternally in the mind of God, an object of divine contemplation. If our attention wanes it is only because we lack the godlike capacity to consider such objects—“the meanest flower that blows” or the cosmic fires overhead—with the attention they deserve. Had we the mind of a philosopher we might be able to observe the distant stars, their light, perhaps a photograph of what once was, and contemplate with love the fate of suns or our own mortality. But we scurry beneath sublimity, and when we glance up we blink.

It is the mind of the writer that makes for the most brilliant essays. Reality—whether the material world of our senses or the intellectual world we apprehend—is of intrinsic interest. It exists, according to some thinkers, eternally in the mind of God, an object of divine contemplation. If our attention wanes it is only because we lack the godlike capacity to consider such objects—“the meanest flower that blows” or the cosmic fires overhead—with the attention they deserve. Had we the mind of a philosopher we might be able to observe the distant stars, their light, perhaps a photograph of what once was, and contemplate with love the fate of suns or our own mortality. But we scurry beneath sublimity, and when we glance up we blink. It was supposed to be the best day of Richard “Blue” Mitchell’s life, but June 30, 1958, turned out to be one of the worst. The trumpeter had been summoned to New York City from Miami for a recording session with Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, an old friend who was being hailed as the hottest alto sax player since Charlie Parker.

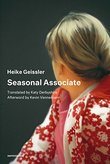

It was supposed to be the best day of Richard “Blue” Mitchell’s life, but June 30, 1958, turned out to be one of the worst. The trumpeter had been summoned to New York City from Miami for a recording session with Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, an old friend who was being hailed as the hottest alto sax player since Charlie Parker. Heike Geissler, the German novelist and translator, ran out of money in the winter of 2010 and took a temporary job at an Amazon warehouse in Leipzig to support her two children. As she tells us in the opening pages of her book about that experience, she was not intending to write a book about that experience. But intention is one thing and canniness another; a real writer’s canniness never deserts her. “Though the work was physically and mentally exhausting,” her translator explains, Geissler “managed to take notes on Post-its” during her six weeks at the warehouse, and write more detailed impressions at night.

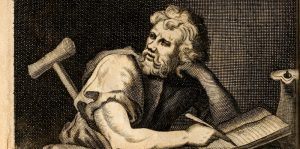

Heike Geissler, the German novelist and translator, ran out of money in the winter of 2010 and took a temporary job at an Amazon warehouse in Leipzig to support her two children. As she tells us in the opening pages of her book about that experience, she was not intending to write a book about that experience. But intention is one thing and canniness another; a real writer’s canniness never deserts her. “Though the work was physically and mentally exhausting,” her translator explains, Geissler “managed to take notes on Post-its” during her six weeks at the warehouse, and write more detailed impressions at night. The chief constraint on personal freedom in ancient Greece and Rome was what Epictetus knew at first hand, the social practice and indignity of slavery. It was slavery, the condition of being literally owned and made to serve at another’s behest that gave ancient freedom its intensely positive value and emotional charge. Slaves’ bodily movements during their waking lives were strictly constrained by their masters’ wishes and by the menial functions they were required to perform. But slaves, like everyone else, had minds, and minds as well as bodies are subject to freedom and constraint. You can be externally free and internally a slave, controlled by psychological masters in the form of disabling desires and passions and cravings. Conversely, you could be outwardly obstructed or even in literal bondage but internally free from frustration and disharmony, so free in fact that you found yourself in charge of your own well-being, lacking little or nothing that you could not provide for yourself. The latter, in essence, is the freedom that Epictetus, the ancient Stoic philosopher, made the central theme of his teaching.

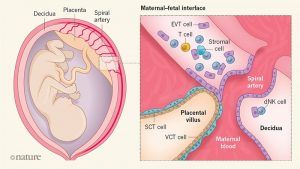

The chief constraint on personal freedom in ancient Greece and Rome was what Epictetus knew at first hand, the social practice and indignity of slavery. It was slavery, the condition of being literally owned and made to serve at another’s behest that gave ancient freedom its intensely positive value and emotional charge. Slaves’ bodily movements during their waking lives were strictly constrained by their masters’ wishes and by the menial functions they were required to perform. But slaves, like everyone else, had minds, and minds as well as bodies are subject to freedom and constraint. You can be externally free and internally a slave, controlled by psychological masters in the form of disabling desires and passions and cravings. Conversely, you could be outwardly obstructed or even in literal bondage but internally free from frustration and disharmony, so free in fact that you found yourself in charge of your own well-being, lacking little or nothing that you could not provide for yourself. The latter, in essence, is the freedom that Epictetus, the ancient Stoic philosopher, made the central theme of his teaching. Scientists have long puzzled over the ‘immunological paradox’ of pregnancy

Scientists have long puzzled over the ‘immunological paradox’ of pregnancy For educated liberals, Jill Lepore is perhaps the most prominent historian in America today. Since 2005, two years after she moved across the Charles River from Boston University to Harvard, Lepore has written dozens of reviews and essays for the New Yorker on everything from Thomas Paine and Kit Carson to Wonder Woman and Rachel Carson. In some ways, this was a surprising development. When Lepore started her career in the Nineties, she specialized in colonial history, a period that many people view as equal parts boring and confusing. Lepore is, however, a gifted researcher and a lively writer, and her early books rightfully garnered acclaim: the first won the Bancroft Prize, and another was a finalist for the Pulitzer.

For educated liberals, Jill Lepore is perhaps the most prominent historian in America today. Since 2005, two years after she moved across the Charles River from Boston University to Harvard, Lepore has written dozens of reviews and essays for the New Yorker on everything from Thomas Paine and Kit Carson to Wonder Woman and Rachel Carson. In some ways, this was a surprising development. When Lepore started her career in the Nineties, she specialized in colonial history, a period that many people view as equal parts boring and confusing. Lepore is, however, a gifted researcher and a lively writer, and her early books rightfully garnered acclaim: the first won the Bancroft Prize, and another was a finalist for the Pulitzer. In just a few weeks, humanity may take its first paid ride into the age of driverless cars.

In just a few weeks, humanity may take its first paid ride into the age of driverless cars. Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has a big goal for a relatively unknown business person: to reach the White House. And he’s aiming to get there by selling America on the idea that all citizens, ages 18-64, should get a check for

Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has a big goal for a relatively unknown business person: to reach the White House. And he’s aiming to get there by selling America on the idea that all citizens, ages 18-64, should get a check for  Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment.

Mitchell settled in the imaginations of pop listeners in the early 70s. In the UK, “Big Yellow Taxi” was a biggish hit in the summer of 1970, its glassily sardonic reflections upon humanity’s relationship with the environment marking out the flaxen-haired Scando-Canadian hippie-chick who sang it as a poster girl for a certain kind of wholesome big-R Romanticism. She was fey, frowning, Nordically bony, the perfect package for the deal: a one-take archetype. What the songs didn’t articulate and the voice didn’t swoop upon like a slender bird, the hair flowed over in a river of molten gold. Like nature busily abhorring a vacuum, Mitchell flooded space that ought perhaps to have been filled by an array of other women before her: the role of thoughtful, poetically articulate, unsentimental, insubordinate, self-expressive female countercultural pop icon. It was a tough job and maybe Mitchell didn’t ask for it, but she certainly got it and then did it with never less than questioning commitment. In 1962 Derrida published a book-length introduction to his translation of Husserl’s short work The Origin of Geometry in which the seeds of his later thinking were already evident, but it was in 1967 that he truly made his mark on the French philosophical scene. In that year he published no fewer than three books, and in so doing displayed the startling originality and productiveness that was to characterize his career until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004: L’écriture et la difference, La voix et le phénomène and De la grammatologie. Five years later, another trio of books appeared, cementing Derrida’s position at the forefront of what became known in the English-speaking world as “post-structuralism”: La Dissemination, Marges de la philosophie and Positions. There followed a steady stream of publications; a recent posthumous volume produced by his favourite French publisher, Galilée, lists fifty-seven books from their own house and another thirty-one from other publishers – and this list includes only the first two volumes in the planned series of hitherto unpublished seminars delivered over more than forty years.

In 1962 Derrida published a book-length introduction to his translation of Husserl’s short work The Origin of Geometry in which the seeds of his later thinking were already evident, but it was in 1967 that he truly made his mark on the French philosophical scene. In that year he published no fewer than three books, and in so doing displayed the startling originality and productiveness that was to characterize his career until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2004: L’écriture et la difference, La voix et le phénomène and De la grammatologie. Five years later, another trio of books appeared, cementing Derrida’s position at the forefront of what became known in the English-speaking world as “post-structuralism”: La Dissemination, Marges de la philosophie and Positions. There followed a steady stream of publications; a recent posthumous volume produced by his favourite French publisher, Galilée, lists fifty-seven books from their own house and another thirty-one from other publishers – and this list includes only the first two volumes in the planned series of hitherto unpublished seminars delivered over more than forty years.

Many people are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he argued that basic needs such as safety, belonging, and self-esteem must be satisfied (to a reasonable healthy degree) before being able to fully realize one’s unique creative and humanitarian potential. What many people may not realize is that a strict hierarchy was not really the focus of his work (and in fact,

Many people are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he argued that basic needs such as safety, belonging, and self-esteem must be satisfied (to a reasonable healthy degree) before being able to fully realize one’s unique creative and humanitarian potential. What many people may not realize is that a strict hierarchy was not really the focus of his work (and in fact,