Carrie Battan at The New Yorker:

In 2016, the singer-songwriters Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, and Phoebe Bridgers, who were all in their early twenties, were living parallel lives. They’d proved themselves to be careful and accomplished writers and performers, and had begun to attract attention from critics and labels alike. Each artist had crafted a distinct sound: Baker, a recovered opioid addict from Memphis, whose musical upbringing was in the Christian church, makes spare and swelling music that draws from the melodies and the ritualized melancholy of the emo world. Bridgers, a Los Angeles native who worshipped Elliott Smith and starred in an Apple commercial at the age of twenty-one, makes folksy, acoustic rock songs whose wispiness cleverly masks their morbid and searing lyrics. (One of her best songs, “Funeral,” details the experience of singing at the funeral of a boy who died of a heroin overdose.) Dacus has a deep, rich voice and makes more conventional rock songs, which she sings from a calm remove. But the three share indisputable similarities: they approach indie rock from a deliberate and plaintive perspective that skews more toward emo, folk, and blues than toward punk, and they write the kind of lyrics that warrant close reading. They are dutiful about guitar-rock songwriting without being explicitly reverential to a particular era.

In 2016, the singer-songwriters Julien Baker, Lucy Dacus, and Phoebe Bridgers, who were all in their early twenties, were living parallel lives. They’d proved themselves to be careful and accomplished writers and performers, and had begun to attract attention from critics and labels alike. Each artist had crafted a distinct sound: Baker, a recovered opioid addict from Memphis, whose musical upbringing was in the Christian church, makes spare and swelling music that draws from the melodies and the ritualized melancholy of the emo world. Bridgers, a Los Angeles native who worshipped Elliott Smith and starred in an Apple commercial at the age of twenty-one, makes folksy, acoustic rock songs whose wispiness cleverly masks their morbid and searing lyrics. (One of her best songs, “Funeral,” details the experience of singing at the funeral of a boy who died of a heroin overdose.) Dacus has a deep, rich voice and makes more conventional rock songs, which she sings from a calm remove. But the three share indisputable similarities: they approach indie rock from a deliberate and plaintive perspective that skews more toward emo, folk, and blues than toward punk, and they write the kind of lyrics that warrant close reading. They are dutiful about guitar-rock songwriting without being explicitly reverential to a particular era.

more here.

Who was the main enemy now? On the right, the answer increasingly was one another. In the 1980s, the conservative movement split into two warring factions—neoconservatives and paleo conservatives. The two sects fought over ideas, but also resources: comfortable think tank positions and administrative posts; grant money and the allegiance of the idle army of increasingly ideologically restive conservative activists who could scare up campaign contributions and votes.

Who was the main enemy now? On the right, the answer increasingly was one another. In the 1980s, the conservative movement split into two warring factions—neoconservatives and paleo conservatives. The two sects fought over ideas, but also resources: comfortable think tank positions and administrative posts; grant money and the allegiance of the idle army of increasingly ideologically restive conservative activists who could scare up campaign contributions and votes. “Before the bedroom there was the room, before that almost nothing”, Perrot announces. She chooses to leapfrog over much medieval history and begin with a description of the king’s bedroom at Versailles under Louis XIV – an account for which she relies heavily on the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, who spoke to the Sun King twice. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is more thorough as an interpreter of the stultifying etiquette of the Versailles system, and Nancy Mitford much funnier; there is no fresh research or information in Perrot’s summary, which is at best indecisive as to the significance of the royal bedroom: “the king’s chamber guards its mysteries”. That said, we learn that Perrot intends to trace the origin of the desire for a “room of one’s own”, which mark of individualization is apparently less universal than it might appear. The Japanese had no notion of privacy, we are told, which might have come as news to the ukiyo-e artists of the seventeenth century; nonetheless, Perrot is broadly correct in her account of the evolution of private sleeping space as depending on the movement from curtained or boxed beds to separate chambers during the same period in Europe.

“Before the bedroom there was the room, before that almost nothing”, Perrot announces. She chooses to leapfrog over much medieval history and begin with a description of the king’s bedroom at Versailles under Louis XIV – an account for which she relies heavily on the memoirs of the duc de Saint-Simon, who spoke to the Sun King twice. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie is more thorough as an interpreter of the stultifying etiquette of the Versailles system, and Nancy Mitford much funnier; there is no fresh research or information in Perrot’s summary, which is at best indecisive as to the significance of the royal bedroom: “the king’s chamber guards its mysteries”. That said, we learn that Perrot intends to trace the origin of the desire for a “room of one’s own”, which mark of individualization is apparently less universal than it might appear. The Japanese had no notion of privacy, we are told, which might have come as news to the ukiyo-e artists of the seventeenth century; nonetheless, Perrot is broadly correct in her account of the evolution of private sleeping space as depending on the movement from curtained or boxed beds to separate chambers during the same period in Europe. According to David Wootton, we are living in a world created by an intellectual revolution initiated by three thinkers in the 16th to 18th centuries. “My title is, Power, Pleasure and Profit, in that order, because power was conceptualised first, in the 16th century, by Niccolò Machiavelli; in the 17th century Hobbes radically revised the concepts of pleasure and happiness; and the way in which profit works in the economy was first adequately theorised in the 18th century by Adam Smith.” Before these thinkers, life had been based on the idea of a summum bonum – an all-encompassing goal of human life. Christianity identified it with salvation, Greco-Roman philosophy with a condition in which happiness and virtue were one and the same. For both, human life was complete when the supreme good was achieved.

According to David Wootton, we are living in a world created by an intellectual revolution initiated by three thinkers in the 16th to 18th centuries. “My title is, Power, Pleasure and Profit, in that order, because power was conceptualised first, in the 16th century, by Niccolò Machiavelli; in the 17th century Hobbes radically revised the concepts of pleasure and happiness; and the way in which profit works in the economy was first adequately theorised in the 18th century by Adam Smith.” Before these thinkers, life had been based on the idea of a summum bonum – an all-encompassing goal of human life. Christianity identified it with salvation, Greco-Roman philosophy with a condition in which happiness and virtue were one and the same. For both, human life was complete when the supreme good was achieved. Of the many small humiliations heaped on a young oncologist in his final year of fellowship, perhaps this one carried the oddest bite: A 2-year-old black-and-white cat named Oscar was apparently better than most doctors at predicting when a terminally ill patient was about to die. The story appeared, astonishingly, in The New England Journal of Medicine in the summer of 2007. Adopted as a kitten by the medical staff, Oscar reigned over one floor of the Steere House nursing home in Rhode Island. When the cat would sniff the air, crane his neck and curl up next to a man or woman, it was a sure sign of impending demise. The doctors would call the families to come in for their last visit. Over the course of several years, the cat had curled up next to 50 patients. Every one of them died shortly thereafter. No one knows how the cat acquired his formidable death-sniffing skills. Perhaps Oscar’s nose learned to detect some unique whiff of death — chemicals released by dying cells, say. Perhaps there were other inscrutable signs. I didn’t quite believe it at first, but Oscar’s acumen was corroborated by other physicians who witnessed the prophetic cat in action. As the author of the article wrote: “No one dies on the third floor unless Oscar pays a visit and stays awhile.”

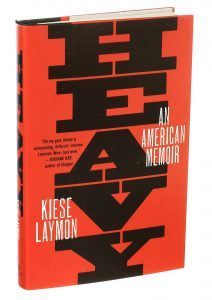

Of the many small humiliations heaped on a young oncologist in his final year of fellowship, perhaps this one carried the oddest bite: A 2-year-old black-and-white cat named Oscar was apparently better than most doctors at predicting when a terminally ill patient was about to die. The story appeared, astonishingly, in The New England Journal of Medicine in the summer of 2007. Adopted as a kitten by the medical staff, Oscar reigned over one floor of the Steere House nursing home in Rhode Island. When the cat would sniff the air, crane his neck and curl up next to a man or woman, it was a sure sign of impending demise. The doctors would call the families to come in for their last visit. Over the course of several years, the cat had curled up next to 50 patients. Every one of them died shortly thereafter. No one knows how the cat acquired his formidable death-sniffing skills. Perhaps Oscar’s nose learned to detect some unique whiff of death — chemicals released by dying cells, say. Perhaps there were other inscrutable signs. I didn’t quite believe it at first, but Oscar’s acumen was corroborated by other physicians who witnessed the prophetic cat in action. As the author of the article wrote: “No one dies on the third floor unless Oscar pays a visit and stays awhile.” Kiese Laymon started his new memoir, “Heavy,” with every intention of writing what his mother would have wanted — something profoundly uplifting and profoundly dishonest, something that did “that old black work of pandering” to American myths and white people’s expectations. His mother, a professor of political science, taught him that you need to lie as a matter of course and, ultimately, to survive; honesty could get a black boy growing up in Jackson, Miss., not just hurt but killed. He wanted to do what she wanted. But then he didn’t.

Kiese Laymon started his new memoir, “Heavy,” with every intention of writing what his mother would have wanted — something profoundly uplifting and profoundly dishonest, something that did “that old black work of pandering” to American myths and white people’s expectations. His mother, a professor of political science, taught him that you need to lie as a matter of course and, ultimately, to survive; honesty could get a black boy growing up in Jackson, Miss., not just hurt but killed. He wanted to do what she wanted. But then he didn’t. I don’t really have heroes, but if I did, Noam Chomsky would be at the top of my list. Who else has achieved such lofty scientific and moral standing? Linus Pauling, perhaps, and Einstein. Chomsky’s arguments about the roots of language, which he first set forth in the late 1950s, triggered a revolution in our modern understanding of the mind. Since the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War, Chomsky has also been a ferocious political critic, denouncing abuses of power wherever he sees them. Chomsky, who turns 90 on December 7, remains busy. He spent last month in Brazil speaking out against far-right politician

I don’t really have heroes, but if I did, Noam Chomsky would be at the top of my list. Who else has achieved such lofty scientific and moral standing? Linus Pauling, perhaps, and Einstein. Chomsky’s arguments about the roots of language, which he first set forth in the late 1950s, triggered a revolution in our modern understanding of the mind. Since the 1960s, when he protested the Vietnam War, Chomsky has also been a ferocious political critic, denouncing abuses of power wherever he sees them. Chomsky, who turns 90 on December 7, remains busy. He spent last month in Brazil speaking out against far-right politician  Language comes naturally to us, but is also deeply mysterious. On the one hand, it manifests as a collection of sounds or marks on paper. On the other hand, it also conveys meaning – words and sentences refer to states of affairs in the outside world, or to much more abstract concepts. How do words and meaning come together in the brain? David Poeppel is a leading neuroscientist who works in many areas, with a focus on the relationship between language and thought. We talk about cutting-edge ideas in the science and philosophy of language, and how researchers have just recently climbed out from under a nineteenth-century paradigm for understanding how all this works.

Language comes naturally to us, but is also deeply mysterious. On the one hand, it manifests as a collection of sounds or marks on paper. On the other hand, it also conveys meaning – words and sentences refer to states of affairs in the outside world, or to much more abstract concepts. How do words and meaning come together in the brain? David Poeppel is a leading neuroscientist who works in many areas, with a focus on the relationship between language and thought. We talk about cutting-edge ideas in the science and philosophy of language, and how researchers have just recently climbed out from under a nineteenth-century paradigm for understanding how all this works. If anxiety about

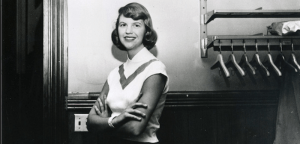

If anxiety about In Plath we have a unique example of rapid, surging development of a poet’s art. In only seven years—from 1956, when the first poems in her Collected Poems were written, to 1963, the year of her death—Plath went from being an obviously talented and excruciatingly ambitious (as her journals attest) apprentice poet with lots of technique and intensity but few real subjects on which to train those powers, to the author of unprecedented works of genius. In Plath’s first book, The Colossus and Other Poems, the only book of poetry she published in her lifetime, we have an unusual opportunity to pinpoint the moments when her art surges forward in particular poems—we can actually watch her grow as an artist, see a little bit how the magic trick was done, and perhaps learn from it. Plath’s earlier poems have a lot to teach about how poets expand their capacities, how they “find” a voice by listening closely to their own minds, and how genius can be, if not made, then at least willfully courted.

In Plath we have a unique example of rapid, surging development of a poet’s art. In only seven years—from 1956, when the first poems in her Collected Poems were written, to 1963, the year of her death—Plath went from being an obviously talented and excruciatingly ambitious (as her journals attest) apprentice poet with lots of technique and intensity but few real subjects on which to train those powers, to the author of unprecedented works of genius. In Plath’s first book, The Colossus and Other Poems, the only book of poetry she published in her lifetime, we have an unusual opportunity to pinpoint the moments when her art surges forward in particular poems—we can actually watch her grow as an artist, see a little bit how the magic trick was done, and perhaps learn from it. Plath’s earlier poems have a lot to teach about how poets expand their capacities, how they “find” a voice by listening closely to their own minds, and how genius can be, if not made, then at least willfully courted. Disregarding the substance of populism and focusing exclusively on its exclusionary rhetoric may succeed in protecting the definition of populism from everyday polemic, however it also allows one to ignore the political issues, in other words what populists are actually saying and why. This, at least, is compatible with the prevailing view that populist positions are so obviously irrational that there is no point in bothering to discuss them anyway. However, this is nothing but the abjuration of the pluralist claim bandied about to characterise populism in the first place. In particular, it enables avoidance of basic questions of redistribution and scarcity, such as that of the losers of cosmopolitan humanitarianism: a question that the (German) middle class no longer likes to talk about, because it hardly comes into contact with them.

Disregarding the substance of populism and focusing exclusively on its exclusionary rhetoric may succeed in protecting the definition of populism from everyday polemic, however it also allows one to ignore the political issues, in other words what populists are actually saying and why. This, at least, is compatible with the prevailing view that populist positions are so obviously irrational that there is no point in bothering to discuss them anyway. However, this is nothing but the abjuration of the pluralist claim bandied about to characterise populism in the first place. In particular, it enables avoidance of basic questions of redistribution and scarcity, such as that of the losers of cosmopolitan humanitarianism: a question that the (German) middle class no longer likes to talk about, because it hardly comes into contact with them. When Burne-Jones painted his Briar Rose cycle, grown women who had too much to say and to do were being forcibly put to bed. They were diagnosed as hysterics, depressives and neurasthenics, whose delicate nerves were no match for their mental gymnastics, and given a prescription of hardcore rest. Many of these women were insomniac. Some had eating disorders; others were suicidal. To a woman (almost) they balked at the societal restrictions that corralled them into being mothers and homemakers and disallowed anything else. Nervous conditions, sleeplessness, self-starvation (that is, disappearing before you are made to disappear), this was their protest.

When Burne-Jones painted his Briar Rose cycle, grown women who had too much to say and to do were being forcibly put to bed. They were diagnosed as hysterics, depressives and neurasthenics, whose delicate nerves were no match for their mental gymnastics, and given a prescription of hardcore rest. Many of these women were insomniac. Some had eating disorders; others were suicidal. To a woman (almost) they balked at the societal restrictions that corralled them into being mothers and homemakers and disallowed anything else. Nervous conditions, sleeplessness, self-starvation (that is, disappearing before you are made to disappear), this was their protest. There were just eight ingredients: two proteins, three buffering agents, two types of fat molecule and some chemical energy. But that was enough to create a flotilla of bouncing, pulsating blobs — rudimentary cell-like structures with some of the machinery necessary to divide on their own. To biophysicist Petra Schwille, the dancing creations in her lab represent an important step towards building a synthetic cell from the bottom up, something she has been working towards for the past ten years, most recently at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, Germany. “I have always been fascinated by this question, ‘What distinguishes life from non-living matter?’” she says. The challenge, according to Schwille, is to determine which components are needed to make a living system. In her perfect synthetic cell, she’d know every single factor that makes it tick.

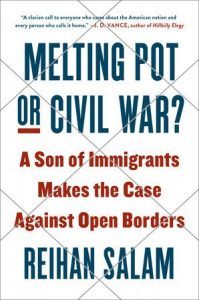

There were just eight ingredients: two proteins, three buffering agents, two types of fat molecule and some chemical energy. But that was enough to create a flotilla of bouncing, pulsating blobs — rudimentary cell-like structures with some of the machinery necessary to divide on their own. To biophysicist Petra Schwille, the dancing creations in her lab represent an important step towards building a synthetic cell from the bottom up, something she has been working towards for the past ten years, most recently at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, Germany. “I have always been fascinated by this question, ‘What distinguishes life from non-living matter?’” she says. The challenge, according to Schwille, is to determine which components are needed to make a living system. In her perfect synthetic cell, she’d know every single factor that makes it tick. Global migration is triggering the sort of existential questions advanced nations haven’t had to bother with very much. Aside from lines on a map and a shared language, what makes Denmark Denmark, or Canada Canada? When does citizen-feeling for national culture and identity — not to mention budget concerns — veer into xenophobia? How much should a modern, secular nation tolerate the illiberal customs of newcomers from traditional cultures? As a “nation of immigrants,” one with a relatively modest welfare state, the United States should be safe from these prickly questions. After all, we have long been a hyphenated citizenry; our children are tutored — or are supposed to be — in E pluribus unum.

Global migration is triggering the sort of existential questions advanced nations haven’t had to bother with very much. Aside from lines on a map and a shared language, what makes Denmark Denmark, or Canada Canada? When does citizen-feeling for national culture and identity — not to mention budget concerns — veer into xenophobia? How much should a modern, secular nation tolerate the illiberal customs of newcomers from traditional cultures? As a “nation of immigrants,” one with a relatively modest welfare state, the United States should be safe from these prickly questions. After all, we have long been a hyphenated citizenry; our children are tutored — or are supposed to be — in E pluribus unum. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, America emerged at the pre-eminent place to be for physics research in the world. Of the 209 people to ever win the Nobel Prize in Physics, a whopping 93 of them claimed United States citizenship: triple that of Germany, the next-closest country. This was reflected not only at the highest levels of prestige and accomplishment in research, but also in education.

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, America emerged at the pre-eminent place to be for physics research in the world. Of the 209 people to ever win the Nobel Prize in Physics, a whopping 93 of them claimed United States citizenship: triple that of Germany, the next-closest country. This was reflected not only at the highest levels of prestige and accomplishment in research, but also in education. There is nothing

There is nothing  Ypres swarms with somber British tourists, who disembark from buses to walk its cobblestone paths, view its seemingly centuries-old shops, homes, and churches, and wander its 175 cemeteries, located outside town amid the famous poppy fields. The ancient architecture and ambience are an illusion. The entire town was destroyed in World War I. Not a single home or tree survived. Churchill argued that Ypres should not be rebuilt: “A more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world,” he thundered. But the residents of Ypres who survived the war insisted on rebuilding.

Ypres swarms with somber British tourists, who disembark from buses to walk its cobblestone paths, view its seemingly centuries-old shops, homes, and churches, and wander its 175 cemeteries, located outside town amid the famous poppy fields. The ancient architecture and ambience are an illusion. The entire town was destroyed in World War I. Not a single home or tree survived. Churchill argued that Ypres should not be rebuilt: “A more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world,” he thundered. But the residents of Ypres who survived the war insisted on rebuilding.